Issue 7, Fall-Winter 1954-1955

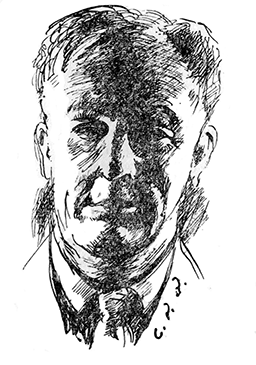

Joyce Cary, 1954.

Joyce Cary, 1954.

Joyce Cary, a sprightly man with an impish crown of gray hair set at a jaunty angle on the back of his head, lives in a high and rather gloomy house in North Oxford. Extremely animated, Mr. Cary’s movements are decisive, uncompromising, and retain some of the brisk alertness of his military career. His speech is overwhelming: voluminous and without hesitation or effort. His rather high voice commands attention, but is expressive and emphatic enough to be a little hard to follow. He is a compactly built, angular man with a keen, determined face, sharp, humorous eyes, and well-defined features. His quick and energetic expressions and bearing create the feeling that it is easier for him to move about than to sit still, and easier to talk than to be silent, even though, like most good talkers, he is a creative and intelligent listener.

His house, a Victorian building with pointed Gothic windows and dark prominent gables, stands opposite the University cricket ground, and just by Keble College. It is a characteristically North Oxford house, contriving to form part of a row without any appearance of being aware of its neighbors. It lies only a little back from the road, behind a small overgrown garden, thick with bushes. The house and garden have all the air of being obstinately “property,” self-contained and a little severe. So we weren’t really surprised at having to wait on the porch and ring away at the bell three or four times, or to learn, when Mr. Cary himself eventually opened the door, that his housekeeper was deaf. A very large grand piano half fills the comfortable room into which we were led. It has one lamp for the treble, another for the bass. The standard of comfort is that of a successful member of the professional class; the atmosphere a little Edwardian, solid, comfortable, unpretentious, with no obtrusive bric-a-brac. Along one wall is a group of representational paintings done by Cary himself in the past. He has, he says, no time for painting now. He is the kind of man who knows exactly what he has time for. So we got down to the questions right away.

INTERVIEWER

Have you by any chance been shown a copy of Barbara Hardy’s essay on your novels in the latest number of Essays in Criticism?

JOYCE CARY

On “Form.” Yes I saw it. Quite good, I thought.

INTERVIEWER

Well, setting the matter of form aside for the moment, we were interested in her attempt to relate you to the tradition of the family chronicle. Is it in fact your conscious intention to recreate what she calls the pseudo-saga?

CARY

Did she say that? Must have skipped that bit.

INTERVIEWER

Well, she didn’t say “consciously,” but we were interested to know whether this was your intention.

CARY

You mean, did I intend to follow up Galsworthy and Walpole? Oh, no, no, no. Family life, no. Family life just goes on. Toughest thing in the world. But of course it is also the microcosm of a world. You get everything there—birth, life, death, love and jealousy, conflict of wills, of authority and freedom, the new and the old. And I always choose the biggest stage possible for my theme.

INTERVIEWER

What about the eighteenth-century novelists? Someone vaguely suggested that you recaptured their spirit, or something of that kind.

CARY

Vaguely is the word. I don’t know who I’m like. I’ve been called a metaphysical novelist, and if that means I have a fairly clear and comprehensive idea of the world I’m writing about, I suppose that’s true.

INTERVIEWER

You mean an idea about the nature of the world that guides the actions of the characters you are creating?

CARY

Not so much the ideas as their background. I don’t care for philosophers in books. They are always bores. A novel should be an experience and convey an emotional truth rather than arguments.

INTERVIEWER

Background—you said background.

CARY

The whole setup—character—of the world as we know it. Roughly, for me, the principal fact of life is the free mind. For good and evil, man is a free creative spirit. This produces the very queer world we live in, a world in continuous creation and therefore continuous change and insecurity. A perpetually new and lively world, but a dangerous one, full of tragedy and injustice. A world in everlasting conflict between the new idea and the old allegiances, new arts and new inventions against the old establishment.

INTERVIEWER

Miss Hardy complains that the form shows too clearly in your novels.

CARY

Others complain that I don’t make the fundamental idea plain enough. This is every writer’s dilemma. Your form is your meaning, and your meaning dictates the form. But what you try to convey is reality—the fact plus the feeling, a total complex experience of a real world. If you make your scheme too explicit, the framework shows and the book dies. If you hide it too thoroughly, the book has no meaning and therefore no form. It is a mess.

INTERVIEWER

How does this problem apply in The Moonlight?

CARY

I was dealing there with the contrast between conventional systems in different centuries—systems created by man’s imagination to secure their lives and give them what they seek from life.