Issue 51, Winter 1971

Pablo Neruda, ca. 1956

“I have never thought of my life as divided between poetry and politics,” Pablo Neruda said in his September 30, 1969, acceptance speech as the Chilean Communist Party candidate for the presidency. “I am a Chilean who for decades has known the misfortunes and difficulties of our national existence and who has taken part in each sorrow and joy of the people. I am not a stranger to them, I come from them, I am part of the people. I come from a working-class family . . . I have never been in with those in power and have always felt that my vocation and my duty was to serve the Chilean people in my actions and with my poetry. I have lived singing and defending them.”

Because of a divided Left, Neruda withdrew his candidacy after four months of hard campaigning and resigned in order to support a Popular Unity candidate. This interview was conducted in his house at Isla Negra in January 1970 just before his resignation.

Isla Negra (Black Island) is neither black nor an island. It is an elegant beach resort forty kilometers south of Valparaiso and a two-hour drive from Santiago. No one knows where the name comes from; Neruda speculates about black rocks vaguely shaped like an island which he sees from his terrace. Thirty years ago, long before Isla Negra became fashionable, Neruda bought—with the royalties from his books—six thousand square meters of beachfront, which included a tiny stone house at the top of a steep slope. “Then the house started growing, like the people, like the trees.”

Neruda has other houses—one on San Cristobal Hill in Santiago and another in Valparaiso. To decorate his houses he has scoured antique shops and junkyards for all kinds of objects. Each object reminds him of an anecdote. “Doesn’t he look like Stalin?” he asks, pointing to a bust of the English adventurer Morgan in the dining room at Isla Negra. “The antique dealer in Paris didn’t want to sell it to me, but when he heard I was Chilean, he asked me if I knew Pablo Neruda. That’s how I persuaded him to sell it.”

It is at Isla Negra where Pablo Neruda, the “terrestrial navigator,” and his third wife, Matilde (“Patoja,” as he affectionately calls her, the “muse” to whom he has written many love poems), have established their most permanent residence.

Tall, stocky, of olive complexion, his outstanding features are a prominent nose and large brown eyes with hooded eyelids. His movements are slow but firm. He speaks distinctly, without pomposity. When he goes for a walk—usually accompanied by his two chows—he wears a long poncho and carries a rustic cane.

At Isla Negra Neruda entertains a constant stream of visitors and there is always room at the table for last-minute guests. Neruda does most of his entertaining in the bar, which one enters through a small corridor from a terrace facing the beach. On the corridor floor is a Victorian bidet and an old hand organ. On the window shelves there is a collection of bottles. The bar is decorated as a ship’s salon, with furniture bolted to the floor and nautical lamps and paintings. The room has glass-panel walls facing the sea. On the ceiling and on each of the wooden crossbeams a carpenter has carved, from Neruda’s handwriting, names of his dead friends.

Behind the bar, on the liquor shelf, is a sign that says no se fia (no credit here). Neruda takes his role as bartender very seriously and likes to make elaborate drinks for his guests although he drinks only Scotch and wine. On a wall are two anti-Neruda posters, one of which he brought back from his last trip to Caracas. It shows his profile with the legend “Neruda go home.” The other is a cover from an Argentine magazine with his picture and the copy “Neruda, why doesn’t he kill himself?” A huge poster of Twiggy stretches from the ceiling to the floor.

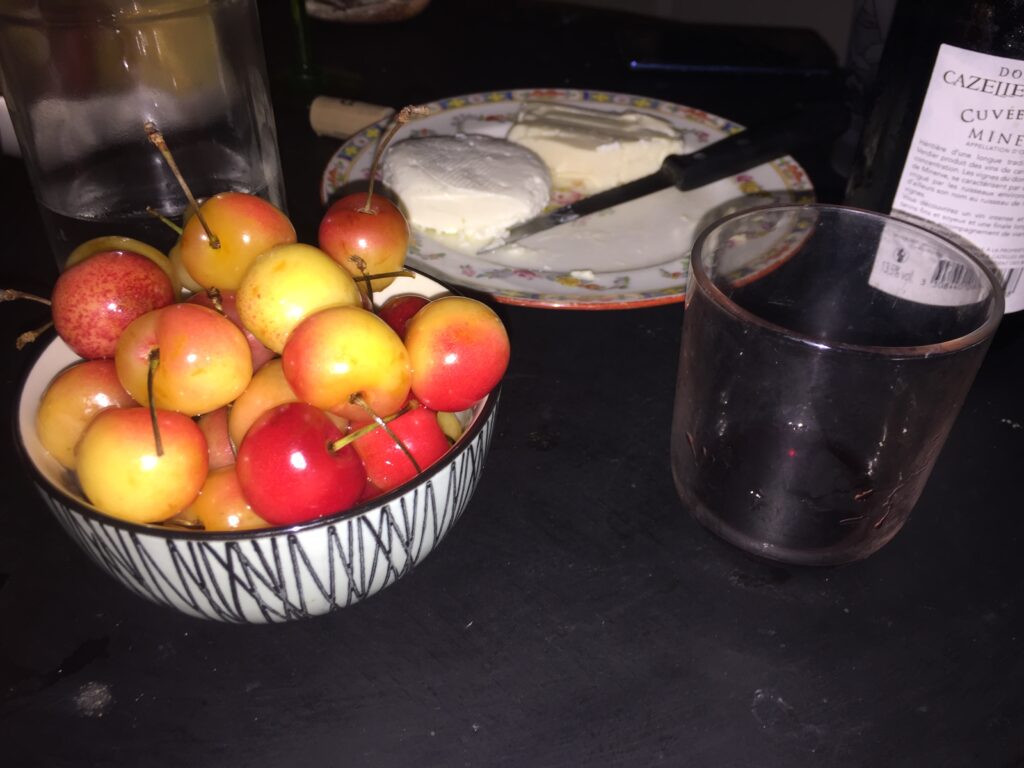

Meals at Isla Negra are typically Chilean. Neruda has mentioned some of them in his poetry: conger-eel soup; fish with a delicate sauce of tomatoes and baby shrimp; meat pie. The wine is always Chilean. One of the porcelain wine pitchers, shaped like a bird, sings when wine is poured. In the summer, lunch is served on a porch facing a garden that has an antique railroad engine. “So powerful, such a corn picker, such a procreator and whistler and roarer and thunderer . . . I love it because it looks like Walt Whitman.”

Conversations for the interview were held in short sessions. In the morning—after Neruda had his breakfast in his room—we would meet in the library, which is a new wing of the house. I would wait while he answered his mail, composed poems for his new book, or corrected the galleys of a new Chilean edition of Twenty Love Poems. When composing poetry, he writes with green ink in an ordinary composition book. He can write a fairly long poem in a very short time, after which he makes only a few corrections. The poems are then typed by his secretary and close friend of more than fifty years, Homero Arce.

In the afternoon, after his daily nap, we would sit on a stone bench on the terrace facing the sea. Neruda would talk holding the microphone of the tape recorder, which picked up the sound of the sea as background to his voice.

INTERVIEWER

Why did you change your name, and why did you choose “Pablo Neruda”?

PABLO NERUDA

I don’t remember. I was only thirteen or fourteen years old. I remember that it bothered my father very much that I wanted to write. With the best of intentions, he thought that writing would bring destruction to the family and myself and, especially, that it would lead me to a life of complete uselessness. He had domestic reasons for thinking so, reasons which did not weigh heavily on me. It was one of the first defensive measures that I adopted—changing my name.

INTERVIEWER

Did you choose “Neruda” because of the Czech poet Jan Neruda?

NERUDA

I’d read a short story of his. I’ve never read his poetry, but he has a book entitled Stories from Malá Strana about the humble people of that neighborhood in Prague. It is possible that my new name came from there. As I say, the whole matter is so far back in my memory that I don’t recall. Nevertheless, the Czechs think of me as one of them, as part of their nation, and I’ve had a very friendly connection with them.

INTERVIEWER

In case you are elected president of Chile, will you keep on writing?

NERUDA

For me writing is like breathing. I could not live without breathing and I could not live without writing.

INTERVIEWER

Who are the poets who have aspired to high political office and succeeded?

NERUDA

Our period is an era of governing poets: Mao Tse Tung and Ho Chi Minh. Mao Tse-tung has other qualities: as you know, he is a great swimmer, something which I am not. There is also a great poet, Léopold Senghor, who is president of Senegal; another, Aimé Césaire, a surrealist poet, is the mayor of Fort-de-France in Martinique. In my country, poets have always intervened in politics, though we have never had a poet who was president of the republic. On the other hand, there have been writers in Latin America who have been president: Rómulo Gallegos was president of Venezuela.

INTERVIEWER

How have you been running your presidential campaign?

NERUDA

A platform is set up. First there are always folk songs, and then someone in charge explains the strictly political scope of our campaign. After that, the note I strike in order to talk to the townspeople is a much freer one, much less organized; it is more poetic. I almost always finish by reading poetry. If I didn’t read some poetry, the people would go away disillusioned. Of course, they also want to hear my political thoughts, but I don’t overwork the political or economic aspects because people also need another kind of language.

INTERVIEWER

How do the people react when you read your poems?

NERUDA

They love me in a very emotional way. I can’t enter or leave some places. I have a special escort which protects me from the crowds because the people press around me. That happens everywhere.

INTERVIEWER

If you had to choose between the presidency of Chile and the Nobel Prize, for which you have been mentioned so often, which would you choose?

NERUDA

There can be no question of a decision between such illusory things.

INTERVIEWER

But if they put the presidency and the Nobel Prize right here on a table?

NERUDA

If they put them on the table in front of me, I’d get up and sit at another table.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think awarding the Nobel Prize to Samuel Beckett was just?

NERUDA

Yes, I believe so. Beckett writes short but exquisite things. The Nobel Prize, wherever it falls, is always an honor to literature. I am not one of those always arguing whether the prize went to the right person or not. What is important about this prize—if it has any importance—is that it confers a title of respect on the office of writer. That is what is important.