Issue 54, Summer 1972

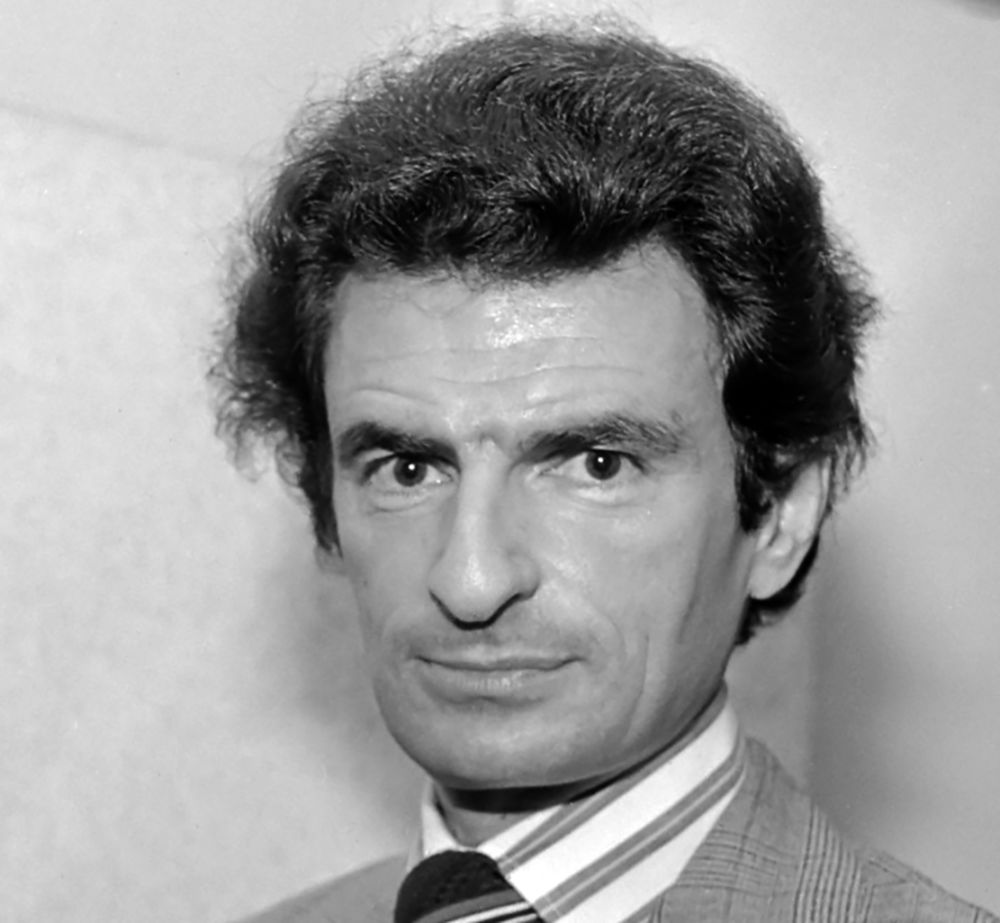

Jerzy Kosinski, ca. 1973. Photograph by Rob Mieremet

Jerzy Kosinski, ca. 1973. Photograph by Rob Mieremet

Editor’s Note: The following conversation with Jerzy Kosinski, which does not contain the customary interviewer’s headnote, is a much expanded version of the one that appeared in The Paris Review in 1972. At that time Mr. Kosinski was traveling abroad and could not be reached when the transcribed text, prepared by interviewers Rocco Landesman and George Plimpton, was ready for his review.

INTERVIEWER

If you had continued to live in Eastern Europe and written in Polish or, as you were bilingual, in Russian, do you think your novels would have been published? And if so, would they have been popular?

JERZY KOSINSKI

It’s not even a matter for speculation. I would never have written in Polish or in Russian. I never saw myself as a man willingly expressing opinions in a totalitarian State. Make no mistake about it: all my generation was perfectly aware of the political price paid for our existence in the total State. To be a writer was to become a spokesman for a particular philosophical dogma. I considered this a trap: I would not speak for it; nor could I publicly speak against it. That’s why I slowly moved toward visual expression: while officially studying social psychology, I became a professional photographer. Of course, there were some other reasons for my apprehension about becoming a writer. Which language would I choose? I was split, like a child who belongs to two different families; studying in Polish at the university, but at home—my parents, even though Polish, were both Russian-born and -educated—all that mattered was Russian tradition and Russian literature.

INTERVIEWER

Given the dimensions of the political trap, could you express in photographs anything you felt?

KOSINSKI

Within the limits of photography, I could contrast collective behavior with individual destiny. Thus, my photographs often portrayed old age, which knows no politics. They showed the solitude of a man alone in an empty field or on a crowded street, and the State buildings and Party memorials, ridiculously monumental, inhuman in their grandeur. My photographs pointed out an independent, naked human being who, even in the total State, was still willing to be photographed naked. I even produced some nudes of rather attractive nonsocialist female forms. It ended on a very unpleasant political note however; at one annual meeting of the Photographers’ Union I was officially accused of being a cosmopolitan who sees the flesh, but not its social implications. My membership in the union and my right to have my photographs published or exhibited nationally or abroad was suspended for an indefinite period. For the same reason, I was also suspended at the university, but then reinstated thanks to my uniformly good grades—and the personal intervention by the dean and the rector, both scholars of “the old guard.”

INTERVIEWER

Who accused you?

KOSINSKI

First, the Party members of the Photographers’ Union. The same politically oriented State setup as the Writers’ Union, you know. These unions control work assignments and permits, exhibitions, grants, awards, etcetera. They are geared to policing; that is what they’re there for. Then my case was picked up by the Party cell of the Students’ Union at the university. By then it was all very serious. One’s whole life depended on an outcome of such an accusation—and of the review of one’s total conduct that followed.

INTERVIEWER

Can one defend oneself?

KOSINSKI

Within the limits of the totalitarian doctrine; there is no defense against the supremacy of the Party that claims to be “the arm of the people.” When I was growing up in a Stalinist society my guidelines were: Am I going to survive physically? Mentally? Am I going to remain a decent being? Will they, the Party, succeed in turning me into their pawn and unleash me against others like me? Since I could not avoid being in conflict with the Party, the unions, the whole totalitarian routine imposed on everyone, my real plight had to remain hidden. I avoided having close friends, men and women who would know too much about me and could be coerced into testifying against me. Still, the accusations, the reprimands, the attacks, continued. I was twice thrown out from the Students’ Union and twice ordered back. From week to week, from meeting to meeting, it was a very perilous existence. Until I left for America I lived the life of an “inner émigré,” as I called myself.

INTERVIEWER

An inner émigré?

KOSINSKI

Yes. The photographic darkroom emerged as a perfect metaphor for my life. It was the one place I could lock myself in (rather than being locked in) and legally not admit anyone else. For me it became a kind of temple. There is an episode in Steps in which a young philosophy student at the State university selects the lavatories as the only temples of privacy available to him. Well, think how much more of such a temple a darkroom is in a police state. Inside, I would develop my own private images; instead of writing fiction I imagined myself as a fictional character. I identified very strongly with characters of both Eastern and Western literature. I saw myself as Pechorin, in Lermontov’s novel, A Hero of Our Time; as Romashov, the hero of Kuprin’s The Duel; as Julien Sorel, or Rastignac, and once in a while as Arthur of E. L. Voynich’s The Gadfly, facing the oppressive society and being at war with it. I wrote my fiction emotionally; I would never commit it to paper.

INTERVIEWER

Paddy Chayefsky said once that he felt these sort of oppressive strictures were really quite important in producing fine literature. He felt that a straitjacket was essential to a writer.

KOSINSKI

Easily said. One could as well argue the opposite and make a point for the Byronesque kind of expression, with its abandonment, its freedom to collide with others, to express outrage—for Nabokov’s kind of vitality. Or we can make a point for a man who chooses a self-imposed visionary straitjacket, perhaps the best one there is. Look at Stendhal, Proust, Melville, Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor. For every Solzhenitsyn who manages to have his first novel published officially (One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovitch), there are probably hundreds of gifted writers in the Soviet bloc who create emotionally in their “darkrooms,” and who will never write anything. Or those very desperate ones who do commit their vision to paper but hide their manuscripts somewhere under the floorboards.

INTERVIEWER

What has been the reaction of the Soviet-bloc press to your achievements in English prose?

KOSINSKI

The reaction of the East European press toward, for example, The Painted Bird was hostile propaganda. They reinvented the content of the novel. Their major effort was to prove that any Pole who settled abroad, writes in English, and is published by various Western publishers had to do it by selling himself to the Library of Congress! According to the official Party journal, the most damaging proof of my collaboration with the White House was that the novel carried the Library of Congress number . . . which, of course, is automatically assigned to every book published in the U.S. There are a few things, however, which they can’t quite cope with: My novels are warmly received by the progressive leftist press in the rest of Western Europe. To counteract it, the East European bureaucrats said that to achieve a “monetary success” in the West, I decided to abandon my “real” idiom, writing instead in English.

INTERVIEWER

Who are the people in the Writers’ Union in the Soviet bloc?

KOSINSKI

They are journalists, novelists, literary critics, poets. They have to pay their bills, and to pay their bills they have to earn income and be published from time to time by the State publishing houses. I think many of them are primarily concerned with survival in their profession. It’s easy to attach labels, but we have to remember they have to function within a most threatening and unpredictable reality governed by the Party bureaucracy and the total State. Hence, many of them are extremely cautious, many tend to be dogmatic, many are just desperate, and some are servile agents of the State organs. The creative man in a police state has always been trapped in a cage where he can fly as long as he does not touch the wires. His predicament is how to spread his wings in the cage. I think the majority fight for sanity, and when one of them says I don’t like this cage, I want out, and does something about it, the others descend on him because he is threatening the safety of all of them. Most often, the writer, poet, or playwright in the Soviet bloc feels that what he writes is the best thing that he can do for his nation, for his country; in good faith he delivers his manuscript to the publisher, and often is persecuted from the next day on—his case discussed by the Writers’ Union because, apparently, according to the accusations, in his manuscript he reveals himself as an anti-Soviet character. This was the case of Pasternak, among many others. When he wrote Doctor Zhivago he thought it was about the fate of a man caught in the changing patterns of political upheavals. Well, the Party didn’t see it that way. Instead, his official accusers declared it antisocialist, cosmopolitan, amoral, etcetera. He was condemned by the Writers’ Union.