Issue 57, Spring 1974

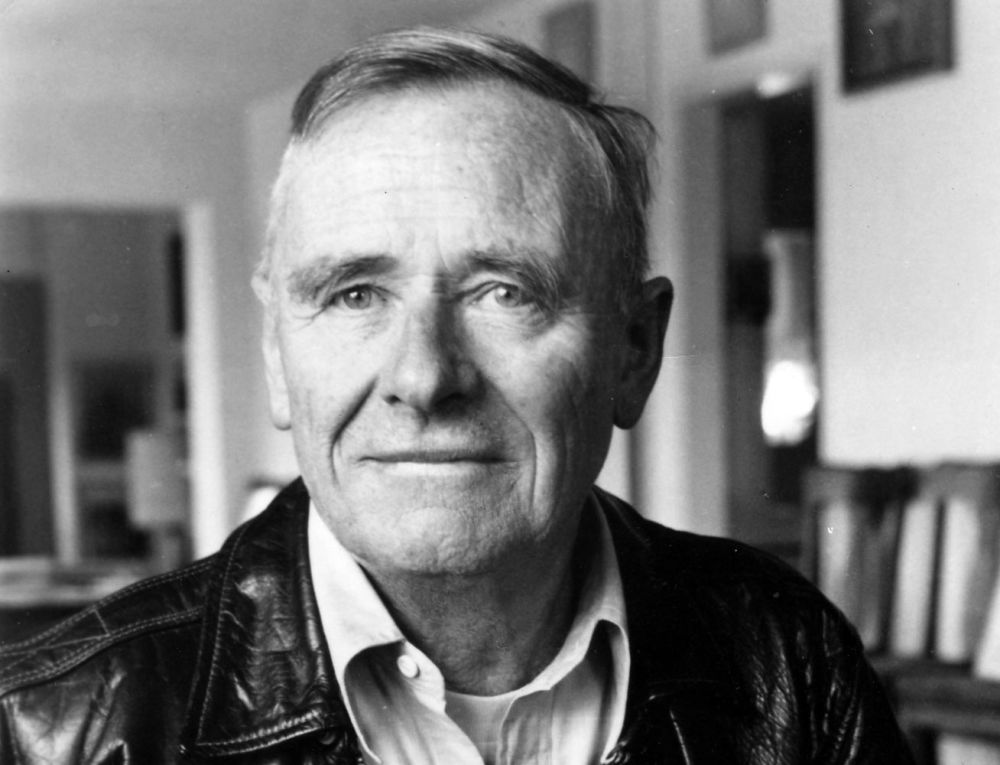

Christopher Isherwood.

Christopher Isherwood.

Christopher Isherwood’s home is in “the canyon” on the edge of Santa Monica, California—a quiet bohemian district of stucco houses inhabited mostly by people involved in the arts. It preserves much of the character it must have had thirty years ago when it first became a haven for refugees from the vast sprawl of Los Angeles. But Demon Change is just around the corner. In 1973 Santa Monica is being Miamified. Pallid apartment blocks with factitious names (Highland Glen, Sunset Towers) are rising all around, and the coastline is dominated by fat piles of concrete.

Still, the developers have not yet hit the Canyon (though they are widening the road amid clouds of dust above Isherwood’s house), and you can see the ocean in the distance, a silvery blue, dotted with wet-suited surfers riding the swell like seals. The house is built into the steep side of the canyon, and you must slither down a driveway, past a garage containing two Volkswagens, side by side, to the door. Isherwood himself opens it and leads the visitor into the living room. He is dressed with great neatness: navy-blue jacket, open shirt, gray, well-pressed pants. He is neatly constructed, too: short, spry (“jockeylike,” said Virginia Woolf), with a lean, suntanned face. His most striking features are the bony, Celtic-looking nose and the pellucid blue eyes, which focus on you in oddly hypnotic fashion, as if observing neither dress, nor mannerisms, but Something Deeper. We agree to drink tea. “Do look around,” he says, “while I make it.”

The living room is high, white, a bit ascetic, but cool despite the hot July afternoon. Nearly all the paintings are modern, including several graphics of the kind that show cubes and cones suspended in space. There are many books, little furniture, and no clutter. A terrace has been added (“We eat breakfast here usually”), and vines cover it. The little houses descend below and climb the far side of the valley. This is the neighborhood lovingly described in A Single Man, by general agreement the finest of Isherwood’s ten novels. There is even a gay bar, which fits exactly a favorite haunt of that book’s protagonist, “down on the corner of the ocean highway, across from the beach, its round green porthole lights shining to welcome you.” But it is called The Friend Ship, not The Starboard Side.

Isherwood looks almost startled when you ask why he lives in California: “Why, it’s my home. I’ve spent almost half my life here.” Originally, he was drawn by the presence of Aldous Huxley and Gerald Heard, with whom he wanted to discuss pacifism and the impending war. There were trips to New York, lectures at universities, a journey across country by bus, and, during the war, after he had registered as a conscientious objector, a spell in Haverford working for a Quaker refugee hostel: “But apart from that I suppose I don’t know this country awfully well. I’ve been an American citizen for—what, nearly thirty years; yet I still seem very British, even to myself. I’ve lived in eleven places in America, and all of them are within sight of this window.”

In recent years, in common with many other writers and artists, Isherwood has become outspoken about the problems and advantages of being homosexual. He has discussed the subject in print and on television (the Cavett show). He says, “For me as a writer, it’s never been a question of ‘homosexuality,’ but of otherness, of seeing things from an oblique angle. If homosexuality were the norm, it wouldn’t be of interest to me as a writer.”

Isherwood works every morning and then usually walks to the ocean to swim. The substance of this interview was therefore recorded in a series of late-afternoon sessions—teatime. Possibly the conversation reflects something of the hour.

INTERVIEWER

You don’t mind if I record this? I have a terrible memory.

CHRISTOPHER ISHERWOOD

Of course not. So do I.

INTERVIEWER

I wanted to ask first how you came to write A Meeting by the River. It seems so different from your earlier novels.

ISHERWOOD

You know of course that I’ve been involved with a Hindu monk, Swami Prabhavananda, for almost the entire length of my life in America—more than thirty years now. A few years ago, there was a centenary of the birth of Vivekananda, who is the chief disciple of Ramakrishna and a great inspirer of Gandhi—he had all kinds of ideas about the future of India. So there was a great national celebration, especially in Bengal, that year, and they decided to have one of those congresses that they so dearly love with speakers from foreign lands; and Swami said would I come along. So I did. At the same time, two monks from the Vedanta monastery here were coming out to India to take their final vows, sannyas, and I was in close contact with their feelings and the whole predicament of being about to take sannyas. For a long time I’d wanted to write a confrontation story where the representative of something meets the representative of something else, and quite suddenly it came to me that this was the way to do it. I talked a great deal with the monks afterward while I was writing it and checked up immensely on the details. I had been to the monastery once before with Don [Bachardy] in 1957, but that was only briefly . . .. It was infinitely more comfortable than the hotel in Calcutta! Perfectly clean, with nice simple little rooms and a place where you washed down with a bucket of water.

INTERVIEWER

Has your involvement with Vedanta changed your life?

ISHERWOOD

It’s made a very great difference, but I couldn’t exactly describe to you what the difference is. I could say what, so to speak, I’ve got out of it. I simply became convinced, after a long period of knowing Swami Prabhavananda, that there is such a thing as mystic union or the knowledge—we get into terrible semantics here—that there is such a thing as mystical experience. That was what seemed to me extraordinary—the thing I had completely dismissed.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a passage in one of your books in which you and Auden are on a train, and you’re savagely attacking religion, and he says: “Be careful, my dear, if you carry on like that, one day you’ll have such a conversion.” Do you think of it in those terms, as a conversion?

ISHERWOOD

Yes. I rather think so. I went through all sorts of attitudes to it. There was a period when I thought I might become a monk myself.

INTERVIEWER

What would that have meant, in practice?

ISHERWOOD

It would have meant living at the Vedanta Center in Los Angeles; I’d probably have spent a great deal of my time helping to translate Hindu classics and increasing my knowledge about Vedanta philosophy; and perhaps giving lectures when I got to be a swami, which I should have been by this time if I’d stayed with it—it’s about twelve years before you take the final vows. Not long after I met Swami Prabhavananda, the war began, and I went to work with the Quakers at a hostel for refugees in Philadelphia, and after 1940 and Pearl Harbor I volunteered to join a Quaker ambulance corps going to China; but they only wanted qualified doctors or automobile mechanics—it was essential to be able to repair the ambulance. Then I would have registered as a conscientious objector and gone to a forestry camp for firefighting—like the one in Paul—but suddenly in the midst of the war they lowered the age limit, and I wasn’t liable for service. I was completely at a loose end, I’d untied all ties; and then Prabhavananda said, “Why don’t you come up to the center and help me translate the Gita,” which we did. There was a general feeling that I might become a monk, but then I decided, rightly or wrongly, that I didn’t have a vocation. But I’ve always remained in touch with Swami Prabhavananda; in fact, I see him every week.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve never been quite sure what people mean when they talk of a vocation.

ISHERWOOD

Well, would you say there is such a thing as having a literary vocation? Let me put it like this: You know the sort of person who goes around thinking I Wish I Were A Writer, and perhaps he does write a bit; and in the end his friends say, well, the trouble was he had no talent. Really, talent is vocation: there is such a thing as having a natural aptitude for a way of life; not everybody can become a monk.

INTERVIEWER

It’s the overwhelming desire to do that thing, then.

ISHERWOOD

Yes, the desire to do that rather than anything else. In the end it would have meant giving up a whole area of my writing.

INTERVIEWER

And you would have to be celibate.

ISHERWOOD

Yes, they make a great point out of that.

INTERVIEWER

All religions do, don’t they?

ISHERWOOD

One has to look at it from two angles, to hear the Hindus explain it. One is that by being celibate, you store up energy; and since there is only one life force, one kind of energy, that is what you are using, in one way or another. Even that Hindu attitude was a tremendous revelation to me. I’d been brought up in this puritanical way to think of flesh and spirit, the low and the high, the forces of lust and the forces of . . . something else. But they think it is the same thing on different levels: The Hindus have this image of what they call a serpent power, that rises through different centers—like an elevator that calls at the lust department on the bottom floor and rises to other levels. That’s one aspect of it—really little more than athletes are told: to lay off while they’re in training. From the other side there is the aspect of being devoted to this search, of avoiding human entanglements and devoting oneself to the love of God. And yet, of course, the Hindus are the first to agree that all love is related, and that one can go a very long way through genuine devotion to another human being. One always talks as if loving someone was simple and easy, but in fact it can be very hard work.