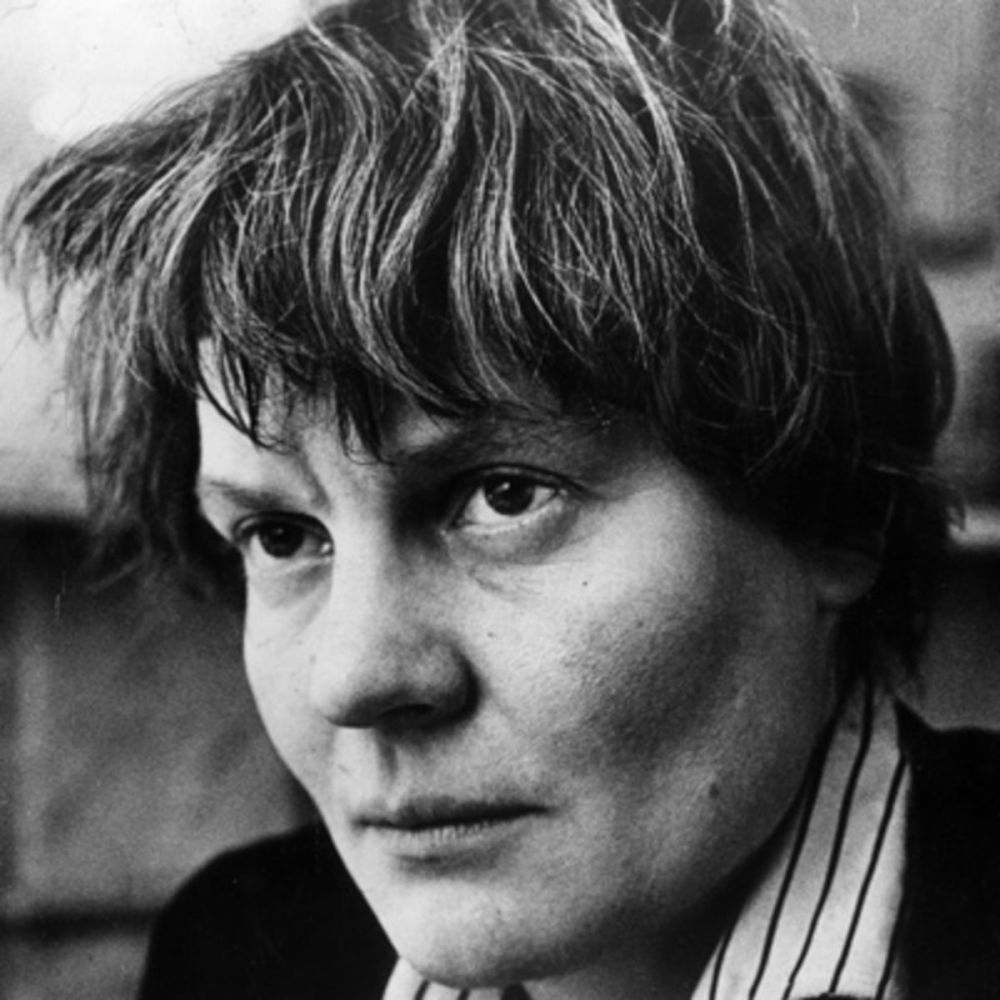

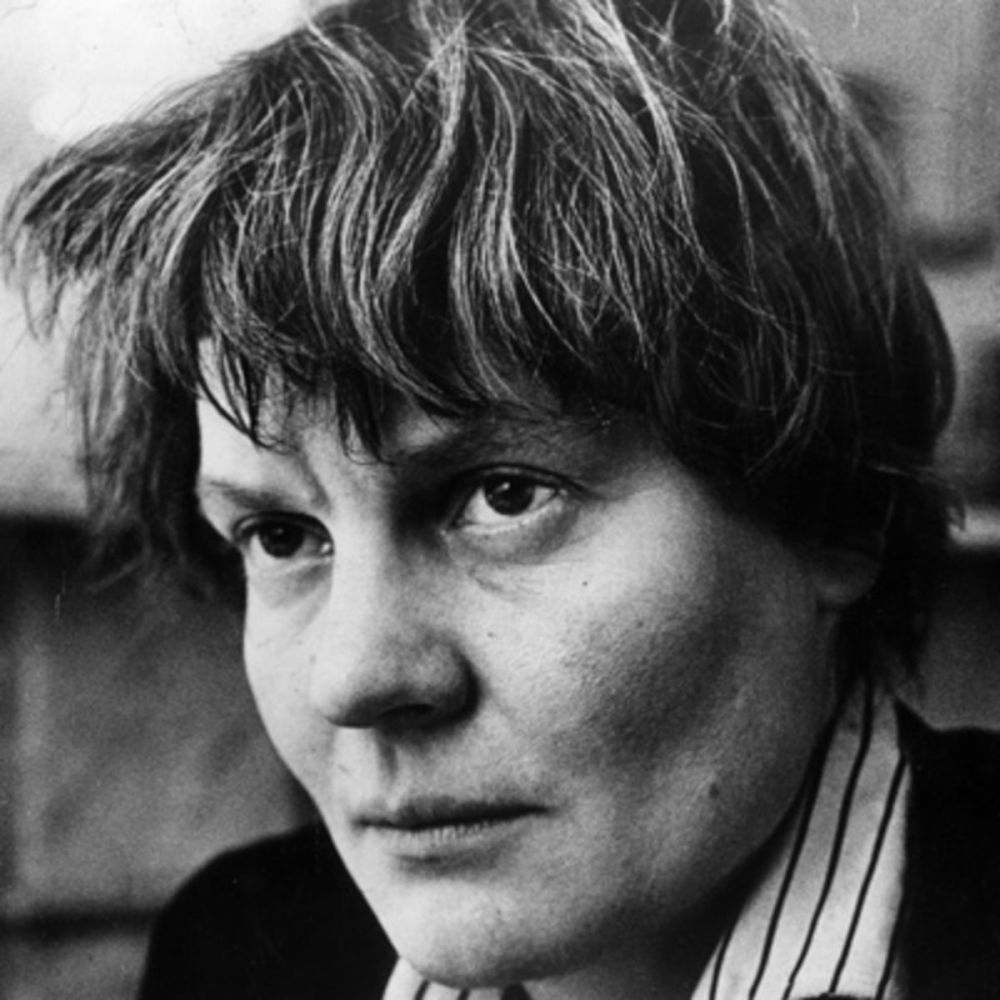

Iris Murdoch was born in Dublin on July 15, 1919 and grew up in London. She was educated at Badminton School in Bristol and studied classics at Somerville College, Oxford from 1938 until 1942, receiving first-class honors. She was assistant principal in the treasury from 1942 to 1944 and an administrative officer with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration in England, Belgium, and Austria during the years 1944 to 1946. She held a Sarah Smithson Studentship in philosophy at Newnham College, Cambridge in 1947–1948, and became a fellow of St. Anne’s College, Oxford, and a university lecturer in philosophy the following year.

She published her first book, Sartre: Romantic Rationalist, in 1953 and her first novel, Under the Net, the next year. Since then she has published twenty-four formal, traditional novels, including The Sandcastle (1957), The Bell (1958), A Severed Head (1961), A Fairly Honourable Defeat (1970), A Word Child (1975), The Sea, The Sea (1978), which won the Booker Prize for that year, The Philosopher’s Pupil (1983), The Good Apprentice (1985), The Book and the Brotherhood (1987), and The Message to the Planet (1989).

Murdoch married John Bayley, an Oxford don, in 1956, and for many years lived in Steeple Aston, a village near Oxfordshire. In 1963 she was named Honorary Fellow of St. Anne’s College, and for the next four years was a part-time lecturer at the Royal College of Art in London. She moved from Steeple Aston to Oxford in 1986.

Though best known as a novelist, she has also published literary criticism, including the influential essay, “Against Dryness” (1961); a volume of poetry, A Year of Birds (1978); three dramatic adaptations (two of which were collaborations) of her novels, as well as two original plays; and an additional three books of philosophy: The Sovereignty of the Good (1970), The Fire and the Sun: Why Plato Banished the Artists (1977) and Acastos: Two Platonic Dialogues (1986).

Iris Murdoch has received many honors. In addition to the Booker Prize, she has won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Black Prince and the Whitbread Literary Award for Fiction for The Sacred and Profane Love Machine, and is an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She was named a companion of the British Empire in 1976 and a dame of the British Empire in 1987.

Murdoch and her husband live in a house in academic north Oxford. In its comfortably untidy rooms books overflow the shelves and are piled high on the floor. Even the bathroom is filled with volumes on language, including Dutch and Esperanto grammar books. Her paper-strewn second-floor study is decorated with oriental rugs and with paintings of horses and children. The first-floor sitting room, which leads out to the garden, has a well-stocked bar. There are paintings and tapestries of flowers, art books and records, pottery and old bottles, and embroidered cushions on the deep sofa.

Additional questions were proposed to Murdoch by James Atlas in front of an audience at the YMHA in New York last spring.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think you could say something about your family?

IRIS MURDOCH

My father went through the first war in the cavalry; it now seems extraordinary to think there was cavalry in World War I. This no doubt saved his life, because, of course, the horses were behind the lines, and in that sense he had a safer war. My parents met at that time. My father’s regiment was based at the Curragh near Dublin and my father was on leave. On his way to church he met my mother, who was going to the same church on the same tram. She sang in the choir. My mother had a very beautiful soprano voice; she was training to be an opera singer and could have been very good indeed, but she gave up her ambitions when she married. She continued singing all her life in an amateur way, but she never realized the potential of that great voice. She was a beautiful, lively, witty woman, with a happy temperament. My parents were very happy together. They loved each other dearly; they loved me and I loved them, so it was a most felicitous trinity.

INTERVIEWER

When did you know you wanted to write?

MURDOCH

I knew very early on that I wanted to be a writer. I mean, when I was a child I knew that. Obviously, the war disturbed all one’s feelings of the future very profoundly. When I finished my undergraduate career I was immediately conscripted because everyone was. Under ordinary circumstances, I would very much have wanted to stay on at Oxford, study for a Ph.D., and try to become a don. I was very anxious to go on learning. But one had to sacrifice one’s wishes to the war. I went into the civil service, into the Treasury where I spent a couple of years. Then after the war I went into UNRRA, the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Association, and worked with refugees in different parts of Europe.

INTERVIEWER

You were a member of the Communist Party, weren’t you?

MURDOCH

I was a member of the Communist Party for a short time when I was a student, about 1939. I went in, as a lot of people did, out of a sense which arose during the Spanish civil war that Europe was dangerously divided between left and right and we were jolly well going to be on the left. We had passionate feelings about social justice. We believed that socialism could, and fairly rapidly, produce just and good societies, without poverty and without strife. I lost those optimistic illusions fairly soon. So I left it. But it was just as well, in a way, to have seen the inside of Marxism because then one realizes how strong and how awful it is, certainly in its organized form. My association with it had its repercussions. Once I was offered a scholarship to come to Vassar. I was longing to go to America—such an adventure after being cooped up in England after the war. One did want to travel and see the world. I was prevented by the McCarren Act, and not given a visa. I may say there was a certain amount of to-do about this. Bertrand Russell got involved and Justice Felix Frankfurter, trying to say how ridiculous this was. But the McCarren Act is made of iron. It’s still here; I have to ask for a waiver if I want to come to the United States.

INTERVIEWER

Even now?

MURDOCH

It’s lunatic. One of the questions sometimes asked by some official is, Can you prove that you are no longer a member of the Communist Party?

INTERVIEWER

I should think that would be very difficult to do.

MURDOCH

Extremely! I left it about fifty years ago!

INTERVIEWER

Could you tell me a little bit about your own method of composition and how you go about writing a novel?

MURDOCH

Well, I think it is important to make a detailed plan before you write the first sentence. Some people think one should write, George woke up and knew that something terrible had happened yesterday, and then see what happens. I plan the whole thing in detail before I begin. I have a general scheme and lots of notes. Every chapter is planned. Every conversation is planned. This is, of course, a primary stage, and very frightening because you’ve committed yourself at this point. I mean, a novel is a long job, and if you get it wrong at the start you’re going to be very unhappy later on. The second stage is that one should sit quietly and let the thing invent itself. One piece of imagination leads to another. You think about a certain situation and then some quite extraordinary aspect of it suddenly appears. The deep things that the work is about declare themselves and connect. Somehow things fly together and generate other things, and characters invent other characters, as if they were all doing it themselves. One should be patient and extend this period as far as possible. Of course, actually writing it involves a different kind of imagination and work.

INTERVIEWER

You are remarkably prolific as a novelist. You seem to enjoy writing a great deal.

MURDOCH

Yes, I do enjoy it, but it has, of course—I mean, this is true of any art form—moments when you think it’s awful, you lose confidence and it’s all black. You can’t think and so on. So, it’s not all enjoyment. But I don’t actually find writing in itself difficult. The creation of the story is the agonizing part. You have the extraordinary experience when you begin a novel that you are now in a state of unlimited freedom, and this is alarming. Every choice you make will exclude another choice, so that it’s rather important what happens then, what state of mind you’re in and what you think matters. Books should have themes. I choose titles carefully and the titles in some way indicate something deep in the theme of the book. Names are important. The names sometimes don’t come at once, but the physical being and the mind of the character have to come pretty early on and you just have to wait for the gods to offer you something. You have to spend a lot of time looking out of the window and writing down scrappy notes that may or may not help. You have to wait patiently until you feel that you’re getting the thing right—who the people are, what it’s all about, how it moves. I may take a long time, say a year, just sitting and fishing around, putting the thing into some sort of shape. Then I do a very detailed synopsis of every chapter, every conversation, everything that happens. That would be another operation.