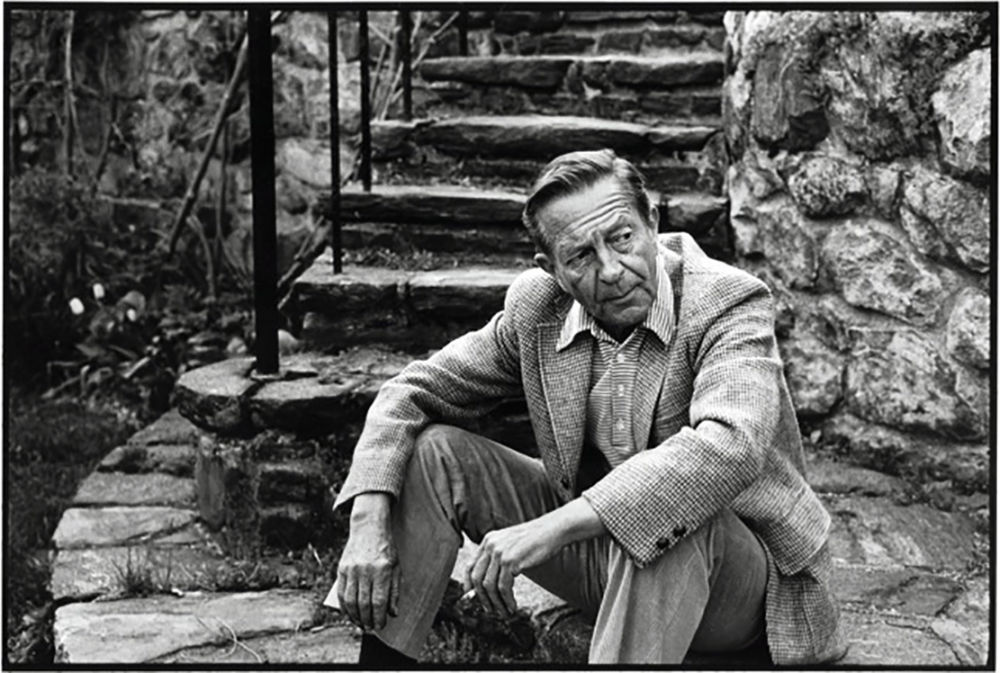

Issue 67, Fall 1976

PHOTOGRAPH BY NANCY CRAMPTON

PHOTOGRAPH BY NANCY CRAMPTON

The first meeting with John Cheever took place in the spring of 1969, just after his novel Bullet Park was published. Normally, Cheever leaves the country when a new book is released, but this time he had not, and as a result many interviewers on the East Coast were making their way to Ossining, New York, where the master storyteller offered them the pleasures of a day in the country—but very little conversation about his book or the art of writing.

Cheever has a reputation for being a difficult interviewee. He does not pay attention to reviews, never rereads his books or stories once published, and is often vague about their details. He dislikes talking about his work (especially into “one of those machines”) because he prefers not to look where he has been, but where he’s going.

For the interview Cheever was wearing a faded blue shirt and khakis. Everything about him was casual and easy, as though we were already old friends. The Cheevers live in a house built in 1799, so a tour of buildings and grounds was obligatory. Soon we were settled in a sunny second-floor study where we discussed his dislike of window curtains, a highway construction near Ossining that he was trying to stop, traveling in Italy, a story he was drafting about a man who lost his car keys at a nude theater performance, Hollywood, gardeners and cooks, cocktail parties, Greenwich Village in the thirties, television reception, and a number of other writers named John (especially John Updike, who is a friend).

Although Cheever talked freely about himself, he changed the subject when the conversation turned to his work. Aren’t you bored with all this talk? Would you like a drink? Perhaps lunch is ready, I’ll just go downstairs and check. A walk in the woods, and maybe a swim afterwards? Or would you rather drive to town and see my office? Do you play backgammon? Do you watch much television?

During the course of several visits we did in fact mostly eat, drink, walk, swim, play backgammon, or watch television. Cheever did not invite me to cut any wood with his chain saw, an activity to which he is rumored to be addicted. On the day of the last taping, we spent an afternoon watching the New York Mets win the World Series from the Baltimore Orioles, at the end of which the fans at Shea Stadium tore up plots of turf for souvenirs. “Isn’t that amazing,” he said repeatedly, referring both to the Mets and their fans.

Afterward we walked in the woods, and as we circled back to the house, Cheever said, “Go ahead and pack your gear, I’ll be along in a minute to drive you to the station” . . . upon which he stepped out of his clothes and jumped with a loud splash into a pond, doubtless cleansing himself with his skinny-dip from one more interview.

INTERVIEWER

I was reading the confessions of a novelist on writing novels: “If you want to be true to reality, start lying about it.” What do you think?

JOHN CHEEVER

Rubbish. For one thing the words “truth” and “reality” have no meaning at all unless they are fixed in a comprehensible frame of reference. There are no stubborn truths. As for lying, it seems to me that falsehood is a critical element in fiction. Part of the thrill of being told a story is the chance of being hoodwinked or taken. Nabokov is a master at this. The telling of lies is a sort of sleight of hand that displays our deepest feelings about life.

INTERVIEWER

Can you give an example of a preposterous lie that tells a great deal about life?

CHEEVER

Indeed. The vows of holy matrimony.

INTERVIEWER

What about verisimilitude and reality?

CHEEVER

Verisimilitude is, by my lights, a technique one exploits in order to assure the reader of the truthfulness of what he’s being told. If he truly believes he is standing on a rug, you can pull it out from under him. Of course, verisimilitude is also a lie. What I’ve always wanted of verisimilitude is probability, which is very much the way I live. This table seems real, the fruit basket belonged to my grandmother, but a madwoman could come in the door any moment.

INTERVIEWER

How do you feel about parting with books when you finish them?

CHEEVER

I usually have a sense of clinical fatigue after finishing a book. When my first novel, The Wapshot Chronicle, was finished, I was very happy about it. We left for Europe and remained there, so I didn’t see the reviews and wouldn’t know of Maxwell Geismar’s disapproval for nearly ten years. The Wapshot Scandal was very different. I never much liked the book, and when it was done I was in a bad way. I wanted to burn the book. I’d wake up in the night and I would hear Hemingway’s voice—I’ve never actually heard Hemingway’s voice, but it was conspicuously his—saying, “This is the small agony. The great agony comes later.” I’d get up and sit on the edge of the bathtub and chain-smoke until three or four in the morning. I once swore to the dark powers outside the window that I would never, never again try to be better than Irving Wallace. It wasn’t so bad after Bullet Park, where I’d done precisely what I wanted: a cast of three characters, a simple and resonant prose style, and a scene where a man saves his beloved son from death by fire. The manuscript was received enthusiastically everywhere, but when Benjamin DeMott dumped on it in the Times, everybody picked up their marbles and ran home. I ruined my left leg in a skiing accident and ended up so broke that I took out working papers for my youngest son. It was simply a question of journalistic bad luck and an overestimation of my powers. However, when you finish a book, whatever its reception, there is some dislodgment of the imagination. I wouldn’t say derangement. But finishing a novel, assuming it’s something you want to do and that you take very seriously, is invariably something of a psychological shock.

INTERVIEWER

How long does it take the psychological shock to wear off? Is there any treatment?

CHEEVER

I don’t quite know what you mean by treatment. To diminish shock I throw high dice, get sauced, go to Egypt, scythe a field, screw. Dive into a cold pool.

INTERVIEWER

Do characters take on identities of their own? Do they ever become so unmanageable that you have to drop them from the work?

CHEEVER

The legend that characters run away from their authors—taking up drugs, having sex operations, and becoming president—implies that the writer is a fool with no knowledge or mastery of his craft. This is absurd. Of course, any estimable exercise of the imagination draws upon such a complex richness of memory that it truly enjoys the expansiveness—the surprising turns, the response to light and darkness—of any living thing. But the idea of authors running around helplessly behind their cretinous inventions is contemptible.

INTERVIEWER

Must the novelist remain the critic as well?

CHEEVER

I don’t have any critical vocabulary and very little critical acumen, and this is, I think, one of the reasons I’m always evasive with interviewers. My critical grasp of literature is largely at a practical level. I use what I love, and this can be anything. Cavalcanti, Dante, Frost, anybody. My library is terribly disordered and disorganized; I tear out what I want. I don’t think that a writer has any responsibility to view literature as a continuous process. I believe that very little of literature is immortal. I’ve known books in my lifetime to serve beautifully, and then to lose their usefulness, perhaps briefly.