Issue 246, Winter 2023

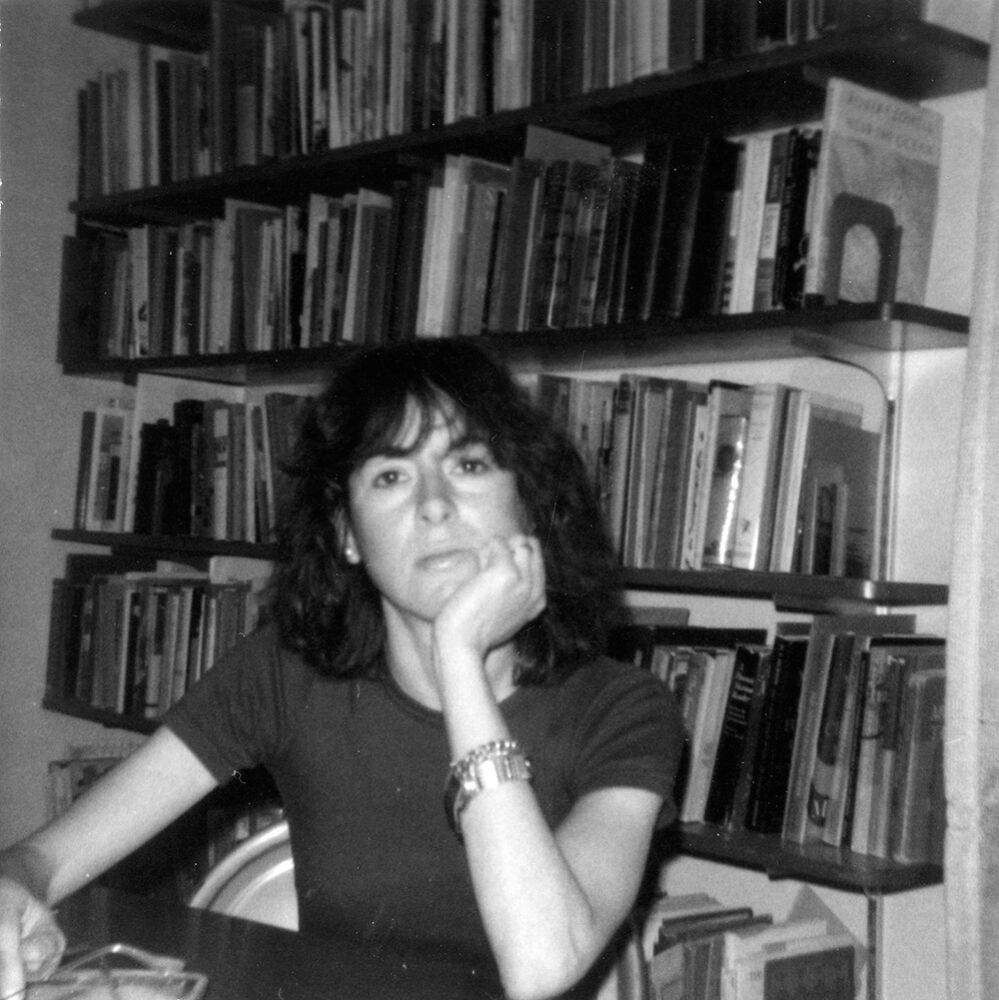

Tucson, Arizona, 1978. photograph by Lois Shelton, © Arizona Board of Regents, courtesy of the University of Arizona Poetry Center.

In early March of 2021, Louise Glück visited Claremont McKenna College in Southern California, where I teach. Because of COVID, she was afraid to fly on a small plane to our regional airport, so I drove her myself from Berkeley, where, for some years, she rented a house during the winters. She packed pumpernickel bagels, apples, and cheese for our six-hour road trip, and she brought CDs of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Rigoletto, Bertolt Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera, and the songs of Jacques Brel, a Belgian master of the modern chanson. Long ago Glück and her former husband had listened to operas on road trips, but this was her first car trip in many years. She knew the musical works backward and forward, pointing out Maria Callas’s vocal strengths and clapping her hands while singing along with Brel. The magnificent almond orchards of central California had just begun to blossom and gleam beside the rolling highway. At the farmers’ market in Claremont, she bought nasturtiums and two baskets of strawberries while talking openly about her girlhood and how she’d weighed only seventy pounds at the worst moment of her anorexia. “But you love food, like a gourmand, Louise,” I said, and she replied, “All anorexics love food.” The hotel where she was staying seemed dingy, but she did not complain. Sitting on the bed cover, she propped herself up with pillows and responded to the endless emails arriving on her mobile phone.

Some months earlier, Glück had won the Nobel Prize in Literature. When the Swedish Academy phoned her quite early in the morning with the marvelous news, she was told that she had twenty-five minutes before the world would know. She immediately called her son, Noah, on the West Coast, and he was joyful after overcoming his panic at hearing the phone ring in the night. Then she called her dearest friend, Kathryn Davis, and her beloved editor, Jonathan Galassi. Reporters quickly appeared on her little dead-end street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Soon she was exhausted from replying to the journalists’ questions, like “Why do you write so frequently about death?” Because of the lockdown, her Nobel medal was presented in the backyard of her condominium. Gray clouds blocked the sun. A light snow and frost covered the yard. The wind gusted. A small folding table was set up in the grass with an ivory cloth that made the gold medal shimmer. I watched the ceremony from Glück’s back patio, on the second floor. She wore black boots, black slacks, a black blouse, a black leather coat with big shearling lapels, and fingerless gloves. A cameraman asked her several times to pick up her medal, and she obeyed, as the wind blew her freshly cut hair across her face. The Swedish consul general explained that normally Glück would have received her medal from the king of Sweden, but that she was standing in for him. The consulate had sent a large bouquet of white amaryllis, but Glück thought they looked wrong in the austere winter scene, so they were removed from the little table. The ceremony took no longer than five minutes, and she shivered silently until she finally asked if she could go inside to warm up.

From the beginning, Glück cited the influence of Blake, Keats, Yeats, and Eliot—poets whose work “craves a listener.” For her, a poem is like a message in a shell held to an ear, confidentially communicating some universal experience: adolescent struggles, marital love, widowhood, separation, the stasis of middle age, aging, and death. There is a porous barrier between the states of life and death and between body and soul. Her signature style, which includes demotic language and a hypnotic pace of utterance, has captured the attention of generations of poets, as it did mine as a nascent poet of twenty-two. In her oeuvre, the poem of language never eclipses the poem of emotion. Like the great poets she admired, she is absorbed by “time which breeds loss, desire, the world’s beauty.”

The conversations that make up this interview mostly took place during the days of Glück’s visit two years ago, which included a rooftop seminar—with the San Gabriel Mountains as a backdrop—and a standing-room-only reading at the Marion Minor Cook Athenaeum, during which she dined with students, an experience that evidently gave her pleasure. She had no desire to undertake a cradle-to-grave interview, but she was happy to converse about her new book, teaching, and craft, and read the version of the interview that I sent her as a work in progress. After her unexpected death on Friday, October 13, 2023, I shared our pages with the Review, since there would be no further conversations.

INTERVIEWER

Am I correct in thinking that you write two kinds of books—one a collection of disparate lyric poems and another that has some of the characteristics of prose, with a narrative thread?

GLÜCK

Yes, and I seem to rotate between the modes. I also think of my books as either operating on a vertical axis, from despair to transcendence, or moving horizontally, with concerns that are more social or communal, the sort of material you might expect to show up in a novel rather than a poem. Averno (2006), for instance, is a book quintessentially on a vertical axis. And A Village Life (2009) is utterly the opposite—with different speakers coming from different times of life, living in some unspecified little seemingly Mediterranean village, though the model was Plainfield, Vermont, where I lived for many years. You make substitutions to keep yourself inventing.

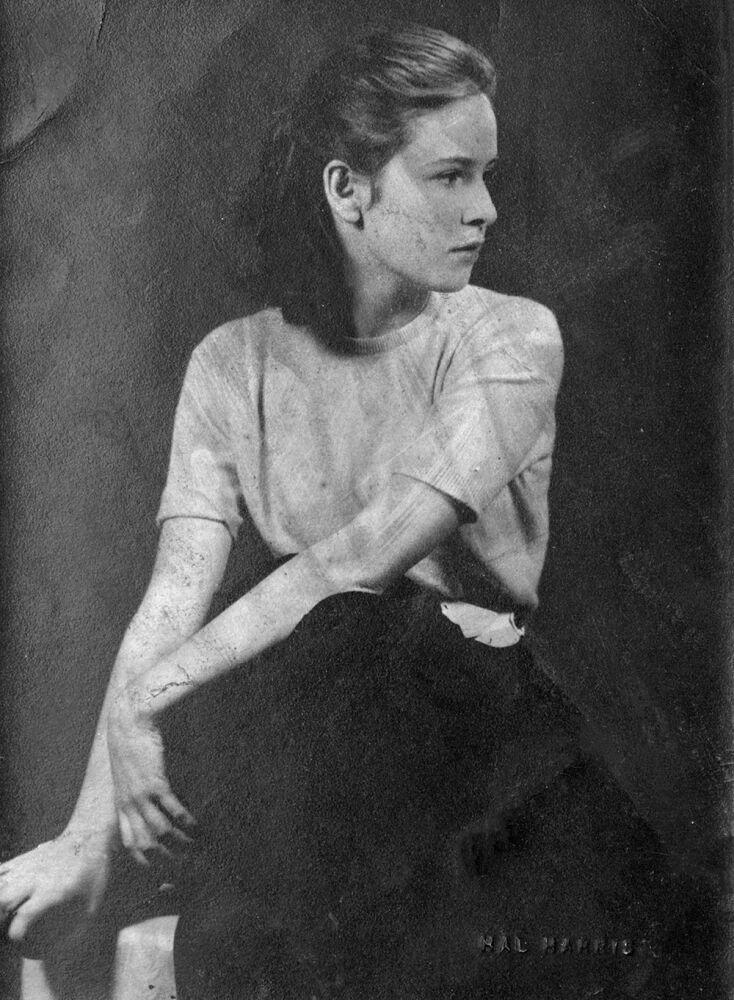

courtesy of the Louise Glück Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

courtesy of the Louise Glück Papers, Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

INTERVIEWER

In your books that move from despair to transcendence, does the divine play a role?

GLÜCK

You could say that the divine is usually at the upper region of the vertical-axis books. In the dark lower region is human flailing—without the divine. Because I’m not a religious person, I would not use this word, divine. But I do think that there is the sense, in the upper regions, of having somehow been rescued and, at the bottom, a sense of having been abandoned.

INTERVIEWER

Where did this idea of a book as one whole thing come from?

GLÜCK

I thought about books that way from the beginning. I was writing short poems, but I wanted to build environments. I wanted to suggest an atmosphere as opposed to a subject or agenda, a meditation or quest as opposed to a stance. Of course, in the early books this isn’t obvious, though I gave great thought to the order of the poems and their implicit arc or trajectory. This attitude became more obvious in Ararat (1990). I remember that when I wrote the first poem—with all flat declarative sentences, no figurative language, no images—I thought the only way it could possibly work was as a whole book, meaning that the flat language had to have, behind and around it, a world.