Issue 213, Summer 2015

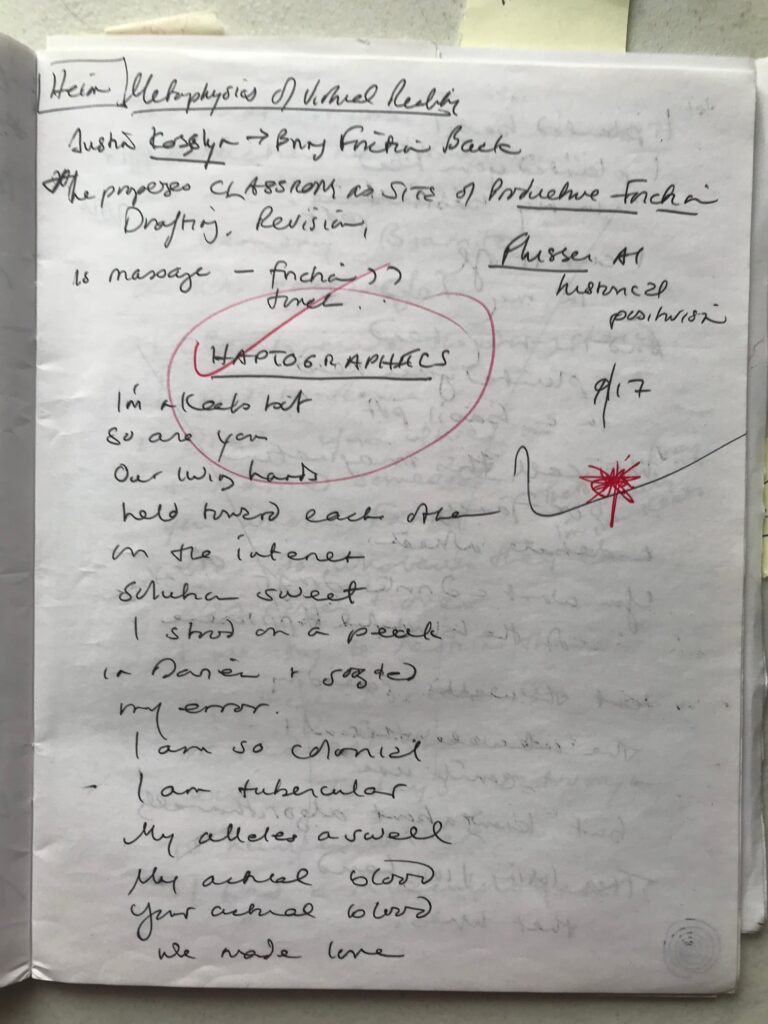

Detail of Cole's temporary Israeli identification card, from 1983

Detail of Cole's temporary Israeli identification card, from 1983

Peter Cole is “a modern / poet of a medieval kind,” one whose work defies traditional distinctions—between old and new, foreign and familiar, translation and original. His vivid, sonorous English translations of secular and mystical Hebrew verse that was previously neglected or regarded as esoteric, parochial, or simply too difficult have remade the American Jewish canon. His renderings of vanguard writers from the contemporary Levant have redrawn the borders between and within Hebrew and Arabic literatures. And then there is Cole’s own poetry, whose rigor, vigor, joy, and wit have expanded the imaginative capacities of what the unimaginative might call his “target language.”

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1957, Cole attended college in the United States—first at Williams and then at Hampshire—before leaving for Jerusalem in 1981. Three decades, two dozen books, and a MacArthur Fellowship later, Cole’s journeying continues: in life, between Israel and the States; and on the page, between al-Andalus and Ashkenaz, Babylon and the Maghreb, the kibbutz and the bulldozed Galilean village. His verse anthology The Dream of the Poem (2007) stirs up the saffron melting pot that was Jewish-Muslim-Christian Spain between 950 and 1492. Another anthology, The Poetry of Kabbalah (2012), braids together nearly two millennia of the lyric, homiletic, and apocalyptic verse of more than thirty Jewish poets, most of them from Arab lands. Other collections are single-author affairs, by such singular writers as the tenebrous Polish-born, Vienna-bred Avraham Ben Yitzhak; the Palestinian maverick Taha Muhammad Ali; the radically self-reinventing Israeli firebrand Aharon Shabtai; his sphinxlike compatriot, the novelist Yoel Hoffmann; and another American-born Jerusalemite, Harold Schimmel, who brought New York School instruction to ancient Hebraic and Arabic forms and just might have inspired Cole to recalibrate the influence in the opposite direction.

Which brings us to the books that bear Cole’s name and only his—Rift (1989), Hymns & Qualms (1998), Things on Which I’ve Stumbled (2008), and, above all, The Invention of Influence (2014). They, too, are made of

That abstract revelation

and slippery duration

to which, it seems, I’m given

and because of which I’m never

finished with anything, as though living

itself were an endless translation

This interview was begun over four days last September in the Ottoman-era house that Cole shares with his wife, the writer Adina Hoffman, in the Musrara neighborhood, on the tense seam between East and West Jerusalem, and was finished, on a cold November night, within the starker walls of the couple’s teaching-term apartment in that other holy city, New Haven.

—Joshua Cohen

INTERVIEWER

We’re in Jerusalem, up on your balcony amid branches of the olive and jacaranda trees, and I can’t help but wonder how it is that an ostensibly secular American poet from New Jersey gets from there to here.

COLE

How else? Through Athens.

INTERVIEWER

Literally or figuratively?

COLE

Both. It was 1979—I was twenty-one years old and had struck up a correspondence with the poet Jack Gilbert, whose early work mattered a great deal to me. He invited me to come to the Aegean island of Paros to study with him, informally. I doubt he used the word study, but that was the upshot. So there I was, having left college for the second time, thrilled and utterly disoriented at the start of what turned into an old-fashioned literary apprenticeship. I lived in a stone hut and built a bed and makeshift kitchen table with scrap wood and a very thick Swiss Army knife. There was no plumbing, no electricity, just a primitive well, which soon went dry. I’d brought almost nothing with me except, idiotically, most of Dante and the complete works of Shakespeare—

INTERVIEWER

And a change of underwear.

COLE

Exactly. One day we were walking into the mountains to visit someone. It was a long hike up through winding trails, we were talking about a little of everything—poets and books, food, plants, childhood, girlfriends—and as he disappeared around a bend while holding forth about something or other, I stopped. It was a little like Balaam’s ass and the angel. I was the ass, of course, and the angel was just an intuition. Jack eventually turned around, saw me standing there, and asked if I was okay. I realize it sounds ridiculous now, and maybe it did then, too—the Big Vision on the Little Mount, or halfway up it—but I said, I think I just saw something about the way I’m going to write . . . I’m not sure I should talk about it. He seemed to think that was a good thing—that I’d seen something grand, or that I’d decided not to bring it into our conversation. But I understood, in a bizarre sort of flash, that, if I was going to be anything as a poet, I was going to be a Jewish poet.

INTERVIEWER

With a name like Peter Cole?

COLE

I’m afraid so. My father was Murray Cohen. My mother was Miriam Levinsohn. Cohen was changed to Cole by all the men on my father’s side of the family. This was Paterson in the thirties and forties. My parents named their children Jon, Peter, and Matthew.

The whole situation was slightly ludicrous. All I understood was the visceral quality of the intuition—in the way that, when I’m beginning a poem of my own or a translation, I often have a sense of the speed and shape and density of the work without knowing anything about its real subject. And it’s clear to me now, as it wasn’t then, that this was a translational situation. It was all about being on the cusp.

INTERVIEWER

Between?

COLE

Well, between Athens and Jerusalem! Which is where I was actually standing at the time, on an island in the Mediterranean. More to the point, I suppose I was suspended between the tradition of American poetry I’d begun training myself in and a nagging but distinctly uninformed experience of Jewishness and Jewish literary history.

INTERVIEWER

Why “nagging”?

COLE

I went to modern Orthodox Jewish day school until I was ten—I was there almost entirely because my more or less assimilated parents wanted to keep me out of the Paterson public-school system. But outside school, I had no connection to that religious world whatsoever. It was all baseball, the world of our father’s law practice, and my mother’s squelched bohemia—she was, and in some senses remained to her dying day, a Martha Graham dancer. My mother’s parents maintained a richer sense of an old-world Jewish home, albeit a secular one. My grandfather on her side was the first pediatrician in Paterson. My father’s father ran a Chevy dealership there.

In any case, within the modern Orthodox biosphere of Jewish day school, I was a mole. I burrowed. For whatever reason, the experience of reading in Hebrew—especially of prayer, and perhaps above all the confusion between reading and prayer—stayed with me powerfully all through childhood. It’s with me still, though I no longer go to synagogue.

INTERVIEWER

Follow that line into the present—what has Hebrew come to mean for you as a writer in American English?

COLE

Hebrew tapped some secret place in me and provided an alternative kind of experience in language. There was also a certain dread that came with that—of my aloneness with those weird, charged letters on the wall, and later on at my twice-weekly suburban Hebrew school, when the rabbi basically just gave me a student’s edition of the book of Genesis and had me translate to keep busy. I have the classic Kittel Bible on my desk now, and the instant I see those large, lickable Hebrew letters cutting into the page or flying off of it—when I’m in that force field, I’m happy as a poet. There’s a kind of . . . what do they call it, not origami . . . umami, a literary umami that the classical Hebrew page releases in me. I think it’s also what I came to want from the English page, and certainly from the ones I write. A certain tang.

I felt it in prayer as well, especially in the disconcerting back and forth across the facing pages of the Hebrew-English prayer book. The opaque but luscious Hebrew on the right-facing page and the inert English translation on the left. It’s as though the English side were blank, and that’s what I’ve been writing into all my life.