Issue 210, Fall 2014

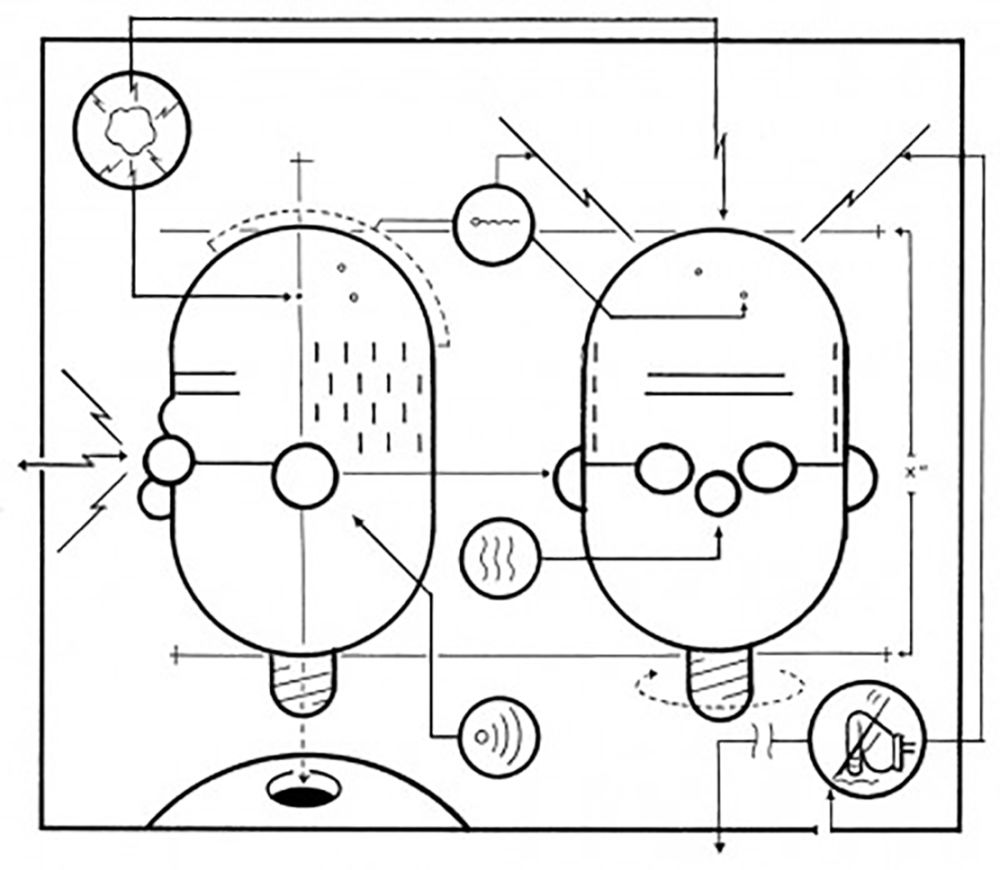

Self-portrait by Chris Ware

Self-portrait by Chris Ware

When you first approach Chris Ware’s house in Oak Park, Illinois, on the western edge of Chicago, it seems like the essence of tree-lined Midwestern normality. Inside, though, it’s a mini-museum, or perhaps a curiosity shop. The decor is early twentieth-century middle class: not antiques but the sturdy products of an age when mass production was still compatible with craft values. It’s not unusual to discover a magic lantern, a phonograph cylinder, or a stereopticon.

Yet in Ware’s house, you’re never quite sure what’s historical relic and what’s his own handiwork. Once on his bookshelf I saw a copy of a book I knew well, a hardcover collection of Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie from 1970. I was puzzled because the cover was unfamiliar, and the book, so far as I knew, had only one edition. As it turned out, Ware was unhappy with the existing cover so he designed and executed a new one for his private use. Ware reacts to anything second-rate or shoddy as an affront; his house is a microcosm of how he might remake the world. Ware delights in finding hidden depths in seemingly antiquated art forms, a tendency also evident in his decision to dedicate his life to renovating comics.

Ware’s studio is on the third floor, in the attic. The windows give him a view of the sidewalk, and on the wall he has a photo of Frank King, the creator of Gasoline Alley. He works on a wooden drafting table, cluttered with rulers and other geometric tools as well as a pencil sharpener of the type found in high schools, attached to which is a note from his daughter, Clara, that reads, “I love your art daddy.” Finished pages hang on hooks so Ware can refer to them as he works on narratives that will take years to complete.

Ware was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1967. He belongs to a recognizable cohort of cartoonists that includes Lynda Barry, Charles Burns, Jaime Hernandez, Gilbert Hernandez, Daniel Clowes, and Seth—all of whom grew up in an era in which comics were still a mass-market staple of childhood, easily available on newsstands. As they grew older, they encountered Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Françoise Mouly, Kim Deitch, and other underground cartoonists who brought comics from the realm of the commercial into that of the personal, and embraced subjects fit for adult readers. Ware’s generation, which came to prominence in the 1980s and ’90s, took the next step, creating comics that aspired to a greater narrative scope. Although Ware’s work has been frequently exhibited in museums and galleries, including at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, it has also been praised by fellow novelists. Zadie Smith has said, “There’s no writer alive whose work I love more than Chris Ware.” Writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books about Ware’s latest book, Building Stories, Rick Moody argued that “the American novel . . . has a lot to learn from this very convincing and masterful work.”

There was some back and forth as to the best way to conduct this interview. An early attempt at a recorded phone conversation failed, the dialogue devolving into a metadiscussion on the interview form and the pitfalls of transcribed interviews. So we settled on e-mail, a form that Ware was more comfortable in and which also allowed him to amplify many points raised in the abortive phone interview.

—Jeet Heer

INTERVIEWER

Is it true that your grandfather wanted to be a cartoonist?

WARE

He took a couple of art classes at the University of Nebraska in the 1910s with vague notions of becoming a cartoonist, but when he and a friend stole some of the dean’s stationery and sent out letters to all the fraternities requiring them to appear at the gymnasium for mandatory VD testing, his college career ended abruptly. He managed to land a job at a newspaper in Lincoln, though, eventually ending up at the Omaha World-Herald, where he worked his way up to sportswriter and editor in the twenties. As late as the 1970s he would still doodle thick-mustached, celluloid-collared cartoon characters for me, the remnants of his earliest ambitions.

Later, as managing editor of the paper, he was responsible for what comics appeared and so was on friendly speaking terms with syndicated cartoonists like Bill Holman and Walt Kelly. He was also one of the earlier editors to add Peanuts. A few of these cartoonists sent him hand-drawn Christmas cards, some of which he framed and hung in his basement office. A few of the guys would even call him up at home. My mom says she remembers talking to Milton Caniff on the phone as a little girl.

INTERVIEWER

She ended up in newspapers, too.

WARE

She did. When she and my father split shortly after I was born, she took a job at the World-Herald and worked very hard to prove herself there, not only as a woman in what was considered a man’s job, but also as the daughter of the managing editor. She quickly became a part of various lunch clubs and occasional afternoon bar hops with the older guys at the paper and held her own both intellectually and professionally. She was, and still is, an excellent writer, to say nothing of extremely smart. When Art Spiegelman met her at my home in Chicago, he called her a “firecracker.”

As a kid, I’d go downtown with her on weekends when she was writing or editing a story and sit upstairs at one of the empty desks and draw, or I’d wander around and look at the drafting tables in the art department. I was amazed at the careful work those guys did, and it especially fascinated me to see how a drawing could be transferred from one piece of paper to a plate of metal to thousands of copies printed out on the rumbling presses below.

But because she had to work to support me, I also spent a lot of time at my grandparents’ house, and I became very close to them, especially to my grandmother. I’d sit with her at the kitchen table and listen for hours while she told me stories of her childhood and the early years of marriage to my grandfather, memories of the two of them going to bathtub-gin parties and getting so hammered they could hardly drive home, or simple memories of growing up at the turn of the century and the smells and sensations of, well, everything she could recall. She had a genuine talent for storytelling, a peculiar ear and eye for detail and for lively words, which made me feel like I was time traveling when I listened to her. I’m certain that it was this evocative warmth and her peculiar, almost songlike sense of syntax that made me want to become a writer. Or at least a version of one.

INTERVIEWER

What part did comics play in your life when you were growing up?

WARE

I misguidedly viewed superhero comics as a sort of preview of my upcoming adult life and spent more time tracing and copying the pictures than I did reading them. I’d replace the costumes with my own and stick a vision of my grown-up face on the muscular bodies, which I suppose indicated psychological problems of its own, but anyway . . . Maybe comics were a way for me to define myself against my more athletic peers as well as disappear among them, because I imagined I had secret powers I would someday use to prove my moral and physical superiority in a shining burst of revelation in the school lunchroom or gym class or wherever.

It was the Peanuts collections in my grandfather’s basement office that really stayed with me through childhood and into college. Charlie Brown, Linus, Snoopy, and Lucy all felt like real people to me. I even felt so sorry for Charlie Brown at one point that I wrote him a valentine and sent it to the newspaper, hoping he’d get it. I’ve said it many times before, but Charles Schulz is the only writer I’ve continually been reading since I was a kid. And I know I’m not alone. He touched millions of people and introduced empathy to comics, an important step in their transition from a mass medium to an artistic and literary one.

Mostly, though, I watched a lot of TV. A lot. I’m pretty sure half my conscious life was spent “waiting for something good to come on” and puzzling over the inner lives of Darrin and Samantha and the Brady Bunch. I was so anesthetized by it that one afternoon I almost electrocuted myself by mindlessly sucking on an extension cord while watching Star Trek. That moment was something of a wake-up call, actually.

INTERVIEWER

What effect did all that TV watching have on you?

WARE

Television was probably my first real drug. I have little doubt that it fired off the same dopamine receptors in my brain that marijuana later did. Specific hours of my childhood day would be tonally defined by what was on. Monday through Friday at three-thirty meant Gilligan’s Island, and so that particular half hour always took on a sense of bamboo and Mary Ann’s checkered shirt, later to be replaced by the tweed and loafers of My Three Sons. I was sensitive to the broadcast vibe of ABC versus CBS versus NBC versus PBS and to how their particular programs made me feel, even how the particular resolution of each channel was different.

INTERVIEWER

What do you mean?

WARE

Well, ABC always felt sharp and acidic, for some reason, and NBC softer, and I’d associate or think of real moments in my life as being more “ABC” or “NBC,” as if they were adjectives. For years I couldn’t figure out why soap operas felt so nauseating until I discovered it was the thirty frames per second of video versus the twenty-four of film—a very indescribable, felt sort of thing for a kid, like the visual buzz of incandescent versus LED light that’s changing our sense of the world now.

When I started trying to make comics in high school, it’s no surprise that I ended up imitating the feeling and rhythms of television, from the falseness of the characters and situations to the camera cropping of the imagery. By the time I got to college I realized that if I was ever going to do anything meaningful, I had to completely detox from TV, so I quit watching it altogether, and I also very self-consciously tried to eliminate any influence it had on my drawing. I came to deeply distrust the kind of storytelling that defined television and movies—the three-act structure with a protagonist that works commercially for twenty-two-minute passive entertainment but has no relation at all to the possibility for narrative self-revelation on paper.

The problem, of course, is that we humans have craved these constructs and clichés, and we’re now so steeped in them that they’ve restructured our unconscious, which any writer or artist trying to deal with re-creating actual consciousness can’t ignore. And which of course has been a concern of contemporary fiction for decades now.

INTERVIEWER

Did you study art in college?

WARE

I studied painting and printmaking at the University of Texas and took a few experimental film and video classes. I built mechanical sculptures in the woodshop and generally tried anything I could to make myself feel better about my own doubts and inadequacies as a person and potential artist. Thankfully, I received a very thorough liberal arts and literature background, of which I was in sore need, though I was also reading a lot of Faulkner, Carson McCullers, and Hemingway on my own time. I took enough philosophy electives that I even considered minoring in it, but I abandoned that plan when I got a C in symbolic logic. While all this was going on, I also drew daily or weekly strips for the student paper. Sort of schizophrenic, I suppose.

When I look back on those years I’m very grateful to the University of Texas for the tolerant, encouraging atmosphere it provided. I’m especially grateful to one of my painting teachers, Richard Jordan, who encouraged us students to trust our most embarrassing ideas and to question the reasons we thought we were doing certain things.

INTERVIEWER

Then you entered the Art Institute’s MFA program in printmaking. What was your experience like there? And why Chicago?

WARE

The tone was a little different there—less “what are you going to do next?” and more “why are you doing that?”—though this may simply point to a contrasting teaching goal between undergraduate and graduate school. I moved there partly to get away from the horrible hot weather of Texas and partly because I knew Karl Wirsum and Jim Nutt taught at the Art Institute. They’d been defining members of the 1960s and ’70s art group the Hairy Who, which had used the language of comics as a means of expression rather than as a stand-in for the empty crassness of modern culture. I took Jim as an adviser for a year, and even though he told me early on he disliked comics, his acerbic and intelligent observations stuck with me. Years later, I met Karl more informally, when he invited me to visit his inspiring, overflowing home studio. I took life-drawing classes from one of the Art Institute’s few remaining figural artists, Richard Keane, who, coincidentally, had taught Richard Jordan decades before. I was lucky to know him and the art historian Robert Loescher, who were both willing to talk about my comics as stories meant to be read, not just as abstract shapes and colors on a page.