Issue 23, Spring 1960

Drawing by Paul Darrow.

Drawing by Paul Darrow.

Among serious novelists, Aldous Huxley is surely the wittiest and most irreverent. Ever since the early twenties, his name has been a byword for a particular kind of social satire; in fact, he has immortalized in satire a whole period and a way of life. In addition to his ten novels, Huxley has written, during the course of an extremely prolific career, poetry, drama, essays, travel, biography, and history.

Descended from two of the most eminent Victorian families, he inherited science and letters from his grandfather T. H. Huxley and his great-uncle Matthew Arnold respectively. He absorbed both strains in an erudition so unlikely that it has sometimes been regarded as a kind of literary gamesmanship. (In conversation his learning comes out spontaneously, without the slightest hint of premeditation; if someone raises the topic of Victorian gastronomy, for example, Huxley will recite a typical daily menu of Prince Edward, meal by meal, course by course, down to the last crumb.) The plain fact is that Aldous Huxley is one of the most prodigiously learned writers not merely of this century but of all time.

After Eton and Balliol, he became a member of the postwar intellectual upper crust, the society he set out to vivisect and anatomize. He first made his name with such brilliant satires as Antic Hay and Point Counter Point, writing in the process part of the social history of the twenties. In the thirties he wrote his most influential novel, Brave New World, combining satire and science fiction in the most successful of futuristic utopias. Since 1937, when he settled in Southern California, he has written fewer novels and turned his attention more to philosophy, history, and mysticism. Although remembered best for his early satires, he is still productive and provocative as ever.

It is rather odd to find Aldous Huxley in a suburb of Los Angeles called Hollywoodland. He lives in an unpretentious hilltop house that suggests the Tudor period of American real-estate history. On a clear day he can look out across miles of cluttered, sprawling city at a broad sweep of the Pacific. Behind him dry brown hills rise to a monstrous sign that dominates the horizon, proclaiming hollywoodland in aluminum letters twenty feet high.

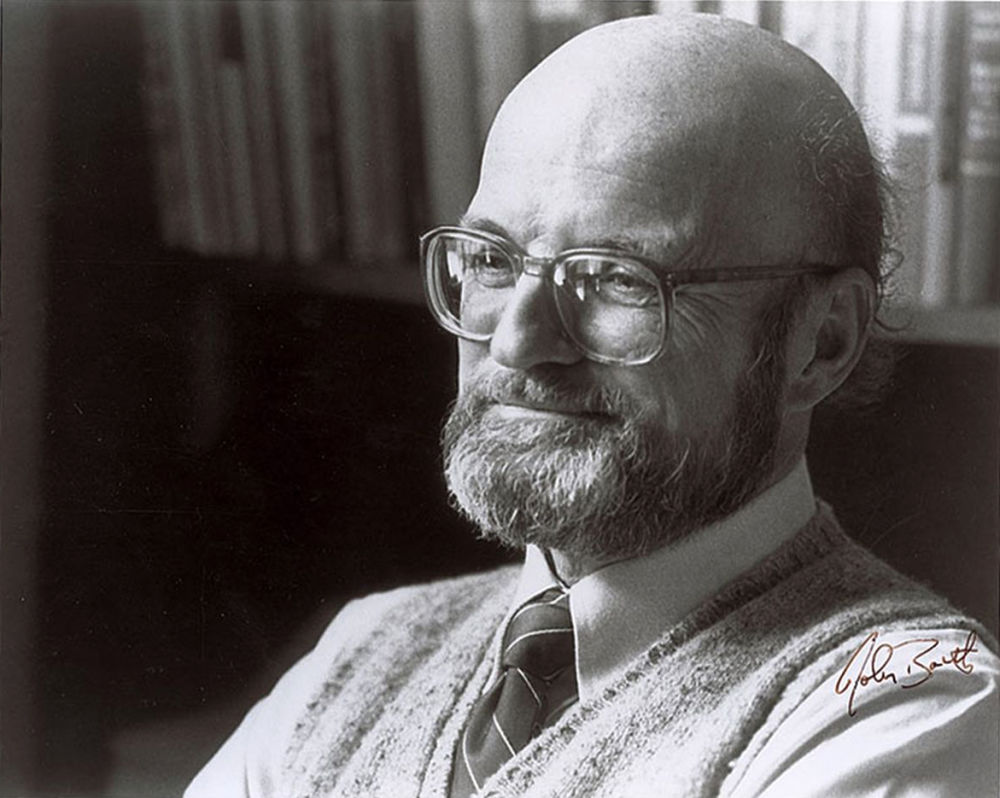

Mr. Huxley is a very tall man—he must be six feet four—and, though lean, very broad across the shoulders. He carries his years lightly indeed; in fact he moves so quietly as to appear weightless, almost wraithlike. His eyesight is limited, but he seems to find his way about instinctively, without touching anything.

In manner and speech he is very gentle. Where one might have been led to expect the biting satirist or the vague mystic, one is impressed instead by how quiet and gentle he is on the one hand, how sensible and down-to-earth on the other. His manner is reflected in his lean, gray, emaciated face: attentive, reflective, and for the most part unsmiling. He listens patiently while others speak, then answers deliberately.

INTERVIEWER

Would you tell us something first about the way you work?

ALDOUS HUXLEY

I work regularly. I always work in the mornings, and then again a little bit before dinner. I’m not one of those who work at night. I prefer to read at night. I usually work four or five hours a day. I keep at it as long as I can, until I feel myself going stale. Sometimes, when I bog down, I start reading—fiction or psychology or history, it doesn’t much matter what—not to borrow ideas or materials, but simply to get started again. Almost anything will do the trick.

INTERVIEWER

Do you do much rewriting?

HUXLEY

Generally, I write everything many times over. All my thoughts are second thoughts. And I correct each page a great deal, or rewrite it several times as I go along.

INTERVIEWER

Do you keep a notebook, like certain characters in your novels?

HUXLEY

No, I don’t keep notebooks. I have occasionally kept diaries for short periods, but I’m very lazy, I mostly don’t. One should keep notebooks, I think, but I haven’t.

INTERVIEWER

Do you block out chapters or plan the overall structure when you start out on a novel?

HUXLEY

No, I work away a chapter at a time, finding my way as I go. I know very dimly when I start what’s going to happen. I just have a very general idea, and then the thing develops as I write. Sometimes—it’s happened to me more than once—I will write a great deal, then find it just doesn’t work, and have to throw the whole thing away. I like to have a chapter finished before I begin on the next one. But I’m never entirely certain what’s going to happen in the next chapter until I’ve worked it out. Things come to me in driblets, and when the driblets come I have to work hard to make them into something coherent.

INTERVIEWER

Is the process pleasant or painful?

HUXLEY

Oh, it’s not painful, though it is hard work. Writing is a very absorbing occupation and sometimes exhausting. But I’ve always considered myself very lucky to be able to make a living at something I enjoy doing. So few people can.

INTERVIEWER

Do you ever use maps or charts or diagrams to guide you in your writing?

HUXLEY

No, I don’t use anything of that sort, though I do read up a good deal on my subject. Geography books can be a great help in keeping things straight. I had no trouble finding my way around the English part of Brave New World, but I had to do an enormous amount of reading up on New Mexico, because I’d never been there. I read all sorts of Smithsonian reports on the place and then did the best I could to imagine it. I didn’t actually go there until six years later, in 1937, when we visited Frieda Lawrence.

INTERVIEWER

When you start out on a novel, what sort of a general idea do you have? How did you begin Brave New World, for example?

HUXLEY

Well, that started out as a parody of H. G. Wells’s Men Like Gods, but gradually it got out of hand and turned into something quite different from what I’d originally intended. As I became more and more interested in the subject, I wandered farther and farther from my original purpose.

INTERVIEWER

What are you working on now?

HUXLEY

At the moment I’m writing a rather peculiar kind of fiction. It’s a kind of fantasy, a kind of reverse Brave New World, about a society in which real efforts are made to realize human potentialities. I want to show how humanity can make the best of both Eastern and Western worlds. So the setting is an imaginary island between Ceylon and Sumatra, at a meeting place of Indian and Chinese influence. One of my principal characters is, like Darwin and my grandfather, a young scientist on one of those scientific expeditions the British Admiralty sent out in the 1840s; he’s a Scotch doctor, who rather resembles James Esdaile, the man who introduced hypnosis into medicine. And then, as in News from Nowhere and other utopias, I have another intruder from the outside world, whose guided tour provides a means of describing the society. Unfortunately, he’s also the serpent in the garden, looking enviously at this happy, prosperous state. I haven’t worked out the ending yet, but I’m afraid it must end with paradise lost—if one is to be realistic.

INTERVIEWER

In the 1946 preface to Brave New World you make certain remarks that seem to prefigure this new utopia. Was the work already incubating then?

HUXLEY

Yes, the general notion was in the back of my mind at that time, and it has preoccupied me a good deal ever since—though not necessarily as the theme for a novel. For a long time I had been thinking a great deal about various ways of realizing human potentialities; then about three years ago I decided to write these ideas into a novel. It’s gone very slowly because I’ve had to struggle with the fable, the framework to carry the expository part. I know what I want to say clearly enough; the problem is how to embody the ideas. Of course, you can always talk them out in dialogue, but you can’t have your characters talking indefinitely without becoming transparent—and tiresome. Then there’s always the problem of point of view: who’s going to tell the story or live the experiences? I’ve had a great deal of trouble working out the plot and rearranging sections that I’ve already written. Now I think I can see my way clear to the end. But I’m afraid it’s getting hopelessly long. I’m not sure what I’m going to do with it all.