Issue 31, Winter-Spring 1964

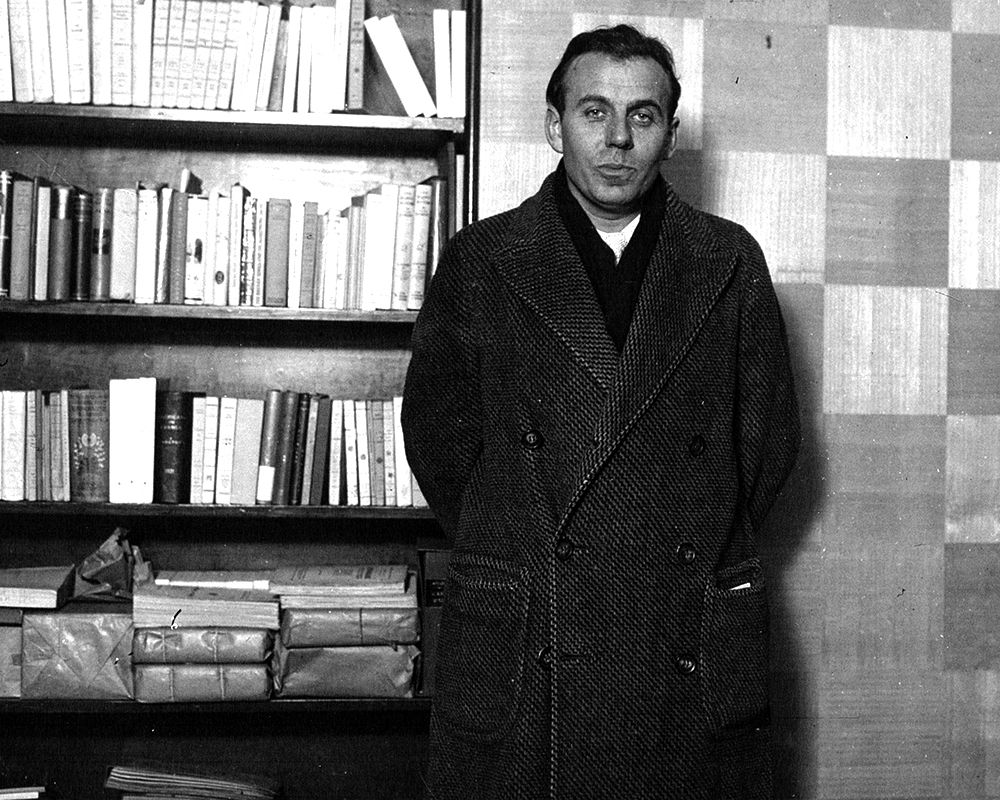

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, ca. 1932.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, ca. 1932.

LOUIS-FERDINAND CÉLINE

So what can I say to you? I don’t know how to please your readers. Those’re people with whom you’ve got to be gentle … You can’t beat them up. They like us to amuse them without abusing them. Good … Let’s talk. An author doesn’t have so many books in him. Journey to the End of the Night, Death on the Installment Plan—that should’ve been enough … I got into it out of curiosity. Curiosity, that’s expensive. I’ve become a tragical chronicler. Most authors are looking for tragedy without finding it. They remember personal little stories which aren’t tragedy. You’ll say: The Greeks. The tragic Greeks had the impression of speaking with the gods … Well, sure … Christ, it’s not everyday you have a chance to telephone the gods.

INTERVIEWER

And for you the tragic in our times?

CÉLINE

It’s Stalingrad. How’s that for catharsis! The fall of Stalingrad is the finish of Europe. There was a cataclysm. The core of it all was Stalingrad. There you can say it was finished and well finished, the white civilization. So all that, it made some noise, some boiling, the guns, the waterfalls. I was in it … I profited off it. I used this stuff. I sell it. Evidently I’ve been mixed up in situations—the Jewish situation—which were none of my business, I had no business being there. Even so I described them … after my fashion.

INTERVIEWER

A fashion that caused a scandal with the appearance of Journey. Your style shook a lot of habits.

CÉLINE

They call that inventing. Take the impressionists. They took their painting one fine day and went to paint outside. They saw how you really lunch on the grass. The musicians worked at it too. From Bach to Debussy there’s a big difference. They’ve caused some revolutions. They’ve stirred the colors, the sounds. For me it’s words, the positions of words. Where French literature’s concerned, there I’m going to be the wise man, make no mistake. We’re pupils of the religions—Catholic, Protestant, Jewish … Well, the Christian religions. Those who directed French education down through the centuries were the Jesuits. They taught us how to make sentences translated from the Latin, well balanced, with a verb, a subject, a complement, a rhythm. In short—here a speech, there a preach, everywhere a sermon! They say of an author, “He knits a nice sentence!” Me, I say, “It’s unreadable.” They say, “What magnificent theatrical language!” I look, I listen. It’s flat, it’s nothing, it’s nil. Me, I’ve slipped the spoken word into print. In one sole shot.

INTERVIEWER

That’s what you call your “little music,” isn’t it?

CÉLINE

I call it “little music” because I’m modest, but it’s a very hard transformation to achieve. It’s work. It doesn’t seem like anything the way it is, but it’s quality. To do a novel like one of mine you have to write eighty thousand pages in order to get eight hundred. Some people say when talking about me, “There’s natural eloquence … He writes like he talks … Those are everyday words … They’re practically identical … You recognize them.” Well, there, that’s “transformation.” That’s just not the word you’re expecting, not the situation you’re expecting. A word used like that becomes at the same time more intimate and more exact than what you usually find there. You make up your style. It helps to get out what you want to show of yourself.

INTERVIEWER

What are you trying to show?

CÉLINE

Emotion. Savy, the biologist, said something appropriate: In the beginning there was emotion, and the verb wasn’t there at all. When you tickle an amoeba she withdraws, she has emotion, she doesn’t speak but she does have emotion. A baby cries, a horse gallops. Only us, they’ve given us the verb. That gives you the politician, the writer, the prophet. The verb’s horrible. You can’t smell it. But to get to the point where you can translate this emotion, that’s a difficulty no one imagines … It’s ugly … It’s superhuman … It’s a trick that’ll kill a guy.

INTERVIEWER

However, you’ve always approved of the need to write.

CÉLINE

You don’t do anything for free. You’ve got to pay. A story you make up, that isn’t worth anything. The only story that counts is the one you pay for. When it’s paid for, then you’ve got the right to transform it. Otherwise it’s lousy. Me, I work … I have a contract, it’s got to be filled. Only I’m sixty-six years old today, I’m seventy-five percent mutilated. At my age most men have retired. I owe six million to Gallimard … so I’m obliged to keep on going … I already have another novel in the works: always the same stuff … It’s chicken feed. I know a few novels. But novels are a little like lace … an art that disappeared with the convents. Novels can’t fight cars, movies, television, booze. A guy who’s eaten well, who’s escaped the big war, in the evenings gives a peck to the old lady and his day’s finished. Done with.

(Interview, later in 1960)

INTERVIEWER

Do you remember having had a shock, a literary explosion, which marked you?

CÉLINE

Oh, never, no! Me, I started in medicine and I wanted medicine and certainly not literature. Jesus Christ, no! If there are any people who seem to me gifted, I’ve seen it in—always the same—Paul Morand, Ramuz, Barbusse, the guys who were made for it.

INTERVIEWER

In your childhood you didn’t think you’d be a writer?

CÉLINE

Oh, not at all, oh, no, no, no. I had an enormous admiration for doctors. Oh, that seemed extraordinary, that did. Medicine was my passion.

INTERVIEWER

In your childhood, what did a doctor represent?

CÉLINE

Just a fellow who came to the passage Choiseul to see my sick mother, my father. I saw a miraculous guy, I did, who cured, who did surprising things to a body which didn’t feel like working. I found that terrific. He looked very wise. I found it absolutely magical.

INTERVIEWER

And today, what does a doctor represent for you?

CÉLINE

Bah! Now he’s so mistreated by society he has competition from everybody, he has no more prestige, no more prestige. Since he’s dressed up like a gas-station attendant, well, bit by bit, he becomes a gas-station attendant. Eh? He doesn’t have much to say anymore, the housewife has Larousse Médical, and then diseases themselves have lost their prestige, there are fewer of them, so look what’s happened: no syph, no gonorrhea, no typhoid. Antibiotics have taken a lot of the tragedy out of medicine. So there’s no more plague, no more cholera.

INTERVIEWER

And the nervous, mental diseases, are there more of those instead?

CÉLINE

Well, there we can’t do anything at all. Some madnesses kill, but not many. But as for the half-mad, Paris is full of them. There’s a natural need to look for excitement, but obviously all the bottoms you see around town inflame the sex drive to a degree … drive the teen-agers nuts, eh?

INTERVIEWER

When you were working at Ford’s, did you have the impression that the way of life imposed on people who worked there risked aggravating mental disturbances?

CÉLINE

Oh, not at all. No. I had a chief doctor at Ford’s who used to say, “They say chimpanzees pick cotton. I say it’d be better to see some working on the machines.” The sick are preferable, they’re much more attached to the factory than the healthy, the healthy are always quitting, whereas the sick stay at the job very well. But the human problem, now, is not medicine. It’s mainly women who consult doctors. Woman is very troubled, because clearly she has every kind of known weakness. She needs … she wants to stay young. She has her menopause, her periods, the whole genital business, which is very delicate, it makes a martyr out of her, doesn’t it, so this martyr lives anyway, she bleeds, she doesn’t bleed, she goes and gets the doctor, she has operations, she doesn’t have operations, she gets re-operated, then in between she gives birth, she loses her shape, all that’s important. She wants to stay young, keep her figure, well. She doesn’t want to do a thing and she can’t do a thing. She hasn’t any muscle. It’s an immense problem … hardly recognized. It supports the beauty parlors, the quacks, and the druggists. But it doesn’t present an interesting medical situation, woman’s decline. It’s obviously a fading rose, you can’t say it’s a medical problem, or an agricultural problem. In a garden, when you see a rose fade, you accept it. Another one will bloom. Whereas in woman, she doesn’t want to die. That’s the hard part.