Issue 63, Fall 1975

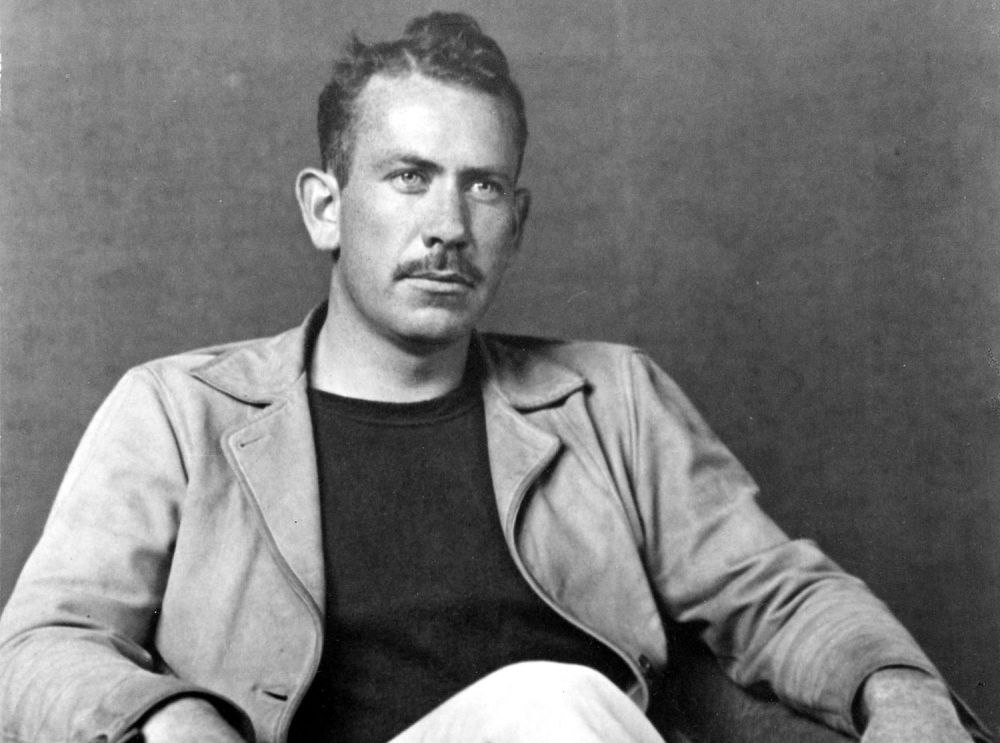

This winter, The Viking Press will publish the fourth volume 0f Writers at Work, continuing its collections of interviews on the craft of fiction from The Paris Review. Included will be the “interview” with John Steinbeck which was published in the Fall 1969, number 48 of The Paris Review. As is recounted in the introduction, Steinbeck had hoped to do a recorded interview with the magazine, but kept postponing it until his death put an end to the matter altogether. In respect to his evinced hope to have something in the magazine on the subject, a composite of material on the craft of his writing was assembled, mostly from his diary kept during the creation of East of Eden (published in December, 1969 by The Viking Press under the title Journey of a Novel).

Since then, much additional material on the subject has been unearthed during the compiling of Steinbeck’s letters (to be published this fall by The Viking Press under the title Steinbeck: A Life in Letters). The “interview” to be published in Writers at Work will incorporate much of this new material some of it not in the collected letters. In some cases, we have substituted letters for material published in the original “interview.”

These new sections appear herewith—the quotes organized under topic headings rather than chronologically, as they are in the diaries.

ON GETTING STARTED

It is usual that the moment you write for publication—I mean one of course—one stiffens in exactly the same way one does when one is being photographed. The simplest way to overcome this is to write it to someone, like me. Write it as a letter aimed at one person. This removes the vague terror of addressing the large and faceless audience and it also, you will find, will give a sense of freedom and a lack of self-consciousness.

—From a letter to Pascal Covici, April 13, 1956

Now let me give you the benefit of my experience in facing 400 pages of blank stock—the appalling stuff that must be filled. I know that no one really wants the benefit of anyone’s experience which is probably why it is so freely offered. But the following are some of the things I have had to do to keep from going nuts.

1. Abandon the idea that you are ever going to finish. Lose track of the 400 pages and write just one page for each day; it helps. Then when it gets finished, you are always surprised.

2. Write freely and as rapidly as possible and throw the whole thing on paper. Never correct or rewrite until the whole thing is down. Rewrite in process is usually found to be an excuse for not going on. It also interferes with flow and rhythm which can only come from a kind of unconscious association with the material.

3. Forget your generalized audience. In the first place, the nameless, faceless audience will scare you to death and in the second place, unlike the theatre, it doesn’t exist. In writing, your audience is one single reader. I have found that sometimes it helps to pick out one person—a real person you know, or an imagined person and write to that one.

4. If a scene or a section gets the better of you and you still think you want it—bypass it and go on. When you have finished the whole you can come back to it and then you may find that the reason it gave trouble is because it didn’t belong there.

5. Beware of a scene that becomes too dear to you, dearer than the rest. It will usually be found that it is out of drawing.

6. If you are using dialogue—say it aloud as you write it. Only then will it have the sound of speech.

—From a letter to Robert Wallsten,

February, 1962

ON INSPIRATION

I hear via a couple of attractive grapevines that you are having trouble writing. God! I know this feeling so well. I think it is never coming back—but it does—one morning, there it is again.

About a year ago. Bob Anderson [the playwright] asked me for help in the same problem. I told him to write poetry—not for selling—not even for seeing—poetry to throw away. For poetry is the mathematics of writing and closely kin to music. And it is also the best therapy because sometimes the troubles come tumbling out.

Well, he did. For six months he did. And I have three joyous letters from him saying it worked. Just poetry—anything and not designed for a reader. It’s a great and valuable privacy.

I only offer this if your dryness goes on too long and makes you too miserable. You may come out of it any day. I have. The words are fighting each other to get out.

—From a letter to Robert Wallsten,

February 19, 1960.