Issue 99, Spring 1986

After living for decades in California, Karl Shapiro now lives at least half the year on New York’s Upper West Side, twenty blocks north of Zabar’s, the landmark food emporium, and ten blocks south of Columbia University. This interview took place in his Morningside Heights apartment, where he lives with his third wife, the translator and editor Sophie Wilkins. The eleventh-floor view from their book-lined apartment overlooks the enormous Cathedral of St. John the Divine. At the time of the interview, late December 1984, Shapiro was busy with two projects—putting together his thirteenth book of poems, and finishing his autobiography. During his lifetime he has received numerous honors, including the Pulitzer Prize in 1945 for his second volume of verse, V-Letter and Other Poems; the Bollingen Prize in Poetry in 1969 for his Selected Poems, a three-hundred and thirty-three page collection from thirty years’ work; appointment as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress; and membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Perhaps his best-known volumes of outspoken criticism are To Abolish Children and Other Essays (1968), and The Poetry Wreck: Selected Essays 1950–1970.

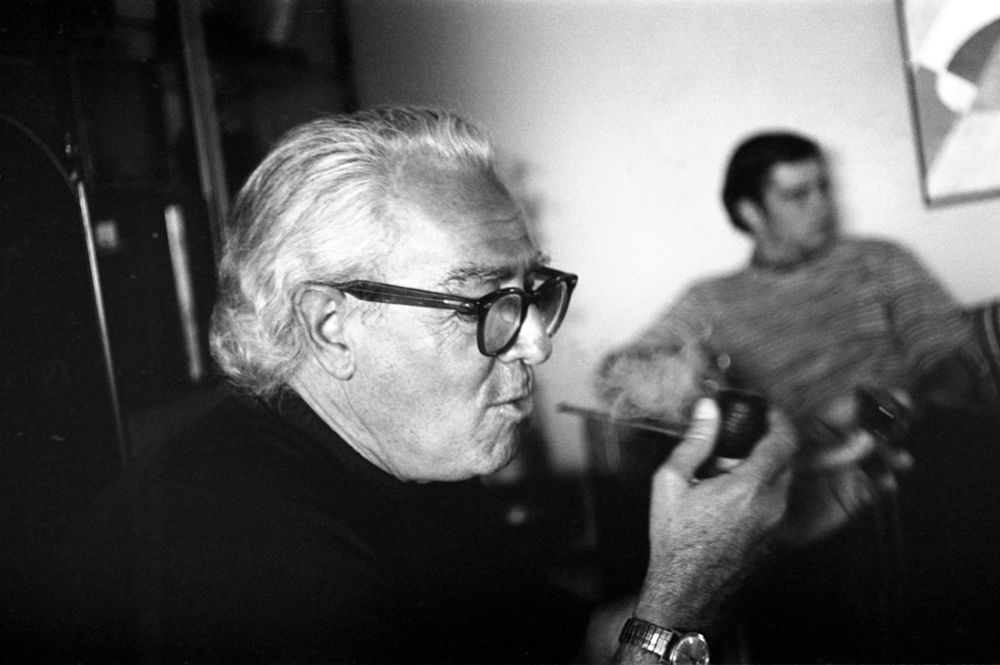

Now seventy-two, he is an energetic and handsome man with a full head of white hair and expressive dark eyes behind plastic-rimmed glasses. What strikes one are his gentleness, his fine manners, and his soft voice—from his essays, one would expect a bit of a wildman. During the hours of the interview—done in one long session—he chain-smoked and sipped a little wine.

INTERVIEWER

You were in the army, during World War II, when your first two books of poems, Person, Place and Thing and V-Letter and Other Poems came out in this country. When you returned from the War, were you aware of having become the literary spokesman of your generation?

KARL SHAPIRO

Words like “spokesman” and “touchstone” took me completely by surprise. For very real reasons. Not only had I been out of the country when my first two books were published, but I have always been “out of the country” in the sense that I never had what ordinarily is thought of as a literary life, or been part of a literary group. What psychiatrists nowadays call a support system. I never had any of that and still don’t. I’ve never been magnetized toward a center like New York. I never even thought of living in New York. When I first started to publish single poems, the place I thought of was Chicago, since Poetry magazine was there. And you didn’t have to live in Chicago to have something printed by them. I thought Poetry was preferable to any magazine that I knew of in New York except perhaps Partisan Review, and that was relatively new and wasn’t specifically poetry anyway. So when I was in the army in New Guinea and finally got the reviews that people sent of my first book, they were all very heady to me. Using words like “spokesman.” I was baffled. I wasn’t sure what the reviewers were talking about, because I had no associations with anybody. I had never met a poet in my life before winning the Pulitzer in 1945. Well, that’s not strictly true; when I went to Johns Hopkins in 1939, W. H. Auden gave a private reading to a group of special literature students, and I was one. I shook hands with him. As it happened, at that time he was my idol, above all others as a modern poet, and that experience was a very sustaining one. But I could hardly say I “knew” him.

INTERVIEWER

How old was Auden then?

SHAPIRO

Well, in 1939—he was born in 1907—he was quite young. He looked it. And he did something that impressed me no end. He read at this club called the Tudor and Stuart, at Johns Hopkins, and he didn’t have his book with him. He recited almost the entire book beautifully, and it included the elegy on Freud and the one on Yeats. That was a magnificent experience! But from my point of view, it was something like a rustic going to the opera. At that time I hadn’t published a thing except a privately-printed book.

INTERVIEWER

Is it true that your wife put your first and second books together during the war in your absence?

SHAPIRO

The first really was an adaptation of a long group of poems that James Laughlin at New Directions had printed in an anthology called Five Young American Poets. Those were published just at the time I was about to be sent overseas, and I begged Laughlin to publish a separate book of mine instead of putting them in that anthology. Well, I was unknown and he wouldn’t do it. He never did a book of mine. But that anthology was the occasion of my first reviews, and they were good ones. After I went overseas, my wife, Evalyn, in fact moved from Baltimore to New York for the purpose of getting more of my work published. She was working as a secretary in some office in Baltimore and had no real ties. She did have friends in Manhattan. I’d send Evalyn individual poems as they were finished. I had no way of sending them to magazines. We were on the move all the time and mail was heavily censored and all mail at that time was sent by ship, which took three to four months. It wasn’t until later in the war they began to photograph letters, those letters called “V-letters” that gave the title to my second collection. Then the mail became faster. Anyway, Evalyn did meet publishers, especially Reynal and Hitchcock, who were then a new firm. Albert Erskine, my lifelong editor, was the editor there and he accepted the book that I called Person, Place and Thing. And when that firm died, I followed Erskine to Random House.

INTERVIEWER

What were the physical circumstances of your writing during the war? Did you have much time off?

SHAPIRO

I was drafted a year before the war, when it was a one-year peacetime draft that people have forgotten about now. And I was in almost a year when Pearl Harbor happened, so I couldn’t get out. But because I was from Baltimore, I was sent to the Medical Corps—all of us who were drafted from Baltimore that first day were sent to the Medical Corps. I guess they knew the war was coming and were trying to build it up. A lot of us were orderlies from hospitals but many were clerks, stenographers, and so on. I was studying in a library school at the time, I was going to be a librarian. But I couldn’t take the final exam because I was drafted. Nobody had ever heard of a student deferment in those days. Because of my background of two years of college at Johns Hopkins, they put me in the company headquarters office and gave me a typewriter.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have access to a typewriter throughout the war?

SHAPIRO

I did. Because I became the company clerk and even in very bad situations, like combat, my job was to be on the typewriter. Although I carried a .45 and a carbine like everyone else.

INTERVIEWER

But what about the availability of a library? You also wrote Essay on Rime when you were stationed in the South Pacific area. It’s full of quotes from Eliot, Auden, Yeats, Cummings, Crane . . .

SHAPIRO

There weren’t that many quotes. Besides, I had a book. I’d met William Van O’Connor [later a literary critic] in New Guinea and we became friends right away. He was stationed at Fort Morely and so was I. We were waiting to go someplace else and Bill gave me his copy of the Oxford Book of Modern Verse, which Yeats had edited. I had that book and I had quotes in my head and there was always a Bible. And that was about it. I later heard there was an army library nearby, but if there was I had never heard of it. Anyway, I wrote Essay on Rime to amuse myself. We had been told that we were going to be in one spot for ninety days with nothing to do. So we were just sitting there waiting to be shipped to the Dutch East Indies. Well, I had the office and the typewriter and the paper, so I blocked out a poem. I figured I wanted to write a poem about poetry, an essay like Pope’s. And I actually diagrammed it—I had never done that before in my life. But I diagrammed how many sections there would be, how many lines per section, how much on prosody and how much on language, and so on. I figured precisely how many lines I would write a day to get the book done in ninety days, and I did it. It was thirty lines a day, and I went to the office every day and wrote those thirty lines. I had no reports to write. The office was deserted.

INTERVIEWER

It’s a prodigious feat.

SHAPIRO

Well, yes, but you see, I had it all in my head—I had read everything on prosody before I was drafted. Don’t forget I’d been working in a big library and I knew a lot about prosody. Nobody ever read prosody books except me. And the rest of the stuff in the poem was simply my ideas about Auden and Williams and the rest.

INTERVIEWER

Then you mailed the book off to your wife?

SHAPIRO

Not all at once. I sent her sections, and a piece appeared in the Kenyon Review and another in the Southern Review.