Issue 119, Summer 1991

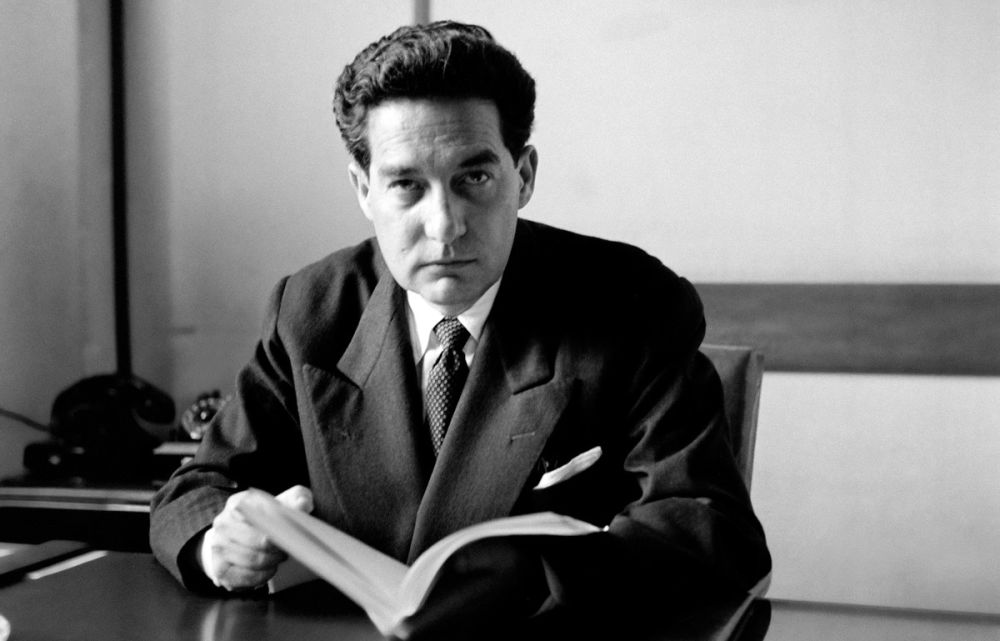

Though small in stature and well into his seventies, Octavio Paz, with his piercing eyes, gives the impression of being a much younger man. In his poetry and his prose works, which are both erudite and intensely political, he recurrently takes up such themes as the experience of Mexican history, especially as seen through its Indian past, and the overcoming of profound human loneliness through erotic love. Paz has long been considered, along with César Vallejo and Pablo Neruda, to be one of the great South American poets of the twentieth century; three days after this interview, which was conducted on Columbus Day 1990, he joined Neruda among the ranks of Nobel laureates in literature.

Paz was born in 1914 in Mexico City, the son of a lawyer and the grandson of a novelist. Both figures were important to the development of the young poet: he learned the value of social causes from his father, who served as counsel for the Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, and was introduced to the world of letters by his grandfather. As a boy, Paz was allowed to roam freely through his grandfather’s expansive library, an experience that afforded him invaluable exposure to Spanish and Latin American literature. He studied literature at the University of Mexico, but moved on before earning a degree.

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Paz sided immediately with the Republican cause and, in 1937, left for Spain. After his return to Mexicao, he helped found the literary reviews Taller (“Workshop”) and El Hijo Pródigo (“The Child Prodigy”) out of which a new generation of Mexican writers emerged. In 1943 Paz traveled extensively in the United States on a Guggenheim Fellowship before entering into the Mexican diplomatic service in 1945. From 1946 until 1951, Paz lived in Paris. The writings of Sartre, Breton, Camus, and other French thinkers whom he met at that same time were to be an important influence on his own work. In the early 1950s Paz’s diplomatic duties took him to Japan and India, where he first came into contact with the Buddhist and Taoist classics. He has said, “More than two thousand years away, Western poetry is essential to Buddhist teaching: that the self is an illusion, a sum of sensations, thoughts, and desire. In October 1968 Paz resigned his diplomatic post to protest the bloody repression of student demonstrations in Mexico City by the government.

His first book of poems, Savage Moon, appeared in 1933 when Paz was nineteen years old. Among his most highly acclaimed works are The Labyrinth of Solitude (1950), a prose study of the Mexican national character, and the book-length poem Sun Stone (1957), called by J. M. Cohen “one of the last important poems to be published in the Western world.” The poem has five hundred and eighty-four lines, representing the five hundred and eighty-four day cycle of the planet Venus. Other works include Eagle or Sun? (1950), Alternating Current (1956), The Bow and the Lyre (1956), Blanco (1967), The Monkey Grammarian (1971), A Draft of Shadows (1975), and A Tree Within (1957).

Paz lives in Mexico City with his wife Marie-José, who is an artist. He has been he recipient of numerous international prizes for poetry, including the International Grand Prix, the Jerusalem Prize (1977), the Neustadt Prize (1982), the Cervantes Prize (1981), and the Novel Prize.

During this interview, which took place in front of an overflow audience at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA in New York, under the auspices of the Poetry Center, Paz displayed the energy and power typical of him and of his poetry, which draws upon an eclectic sexual mysticism to bridge the gap between the individual and society. Appropriately, Paz seemed to welcome this opportunity to communicate with his audience.

INTERVIEWER

Octavio, you were born in 1914, as you probably remember . . .

OCTAVIO PAZ

Not very well!

INTERVIEWER

. . . virtually in the middle of the Mexican Revolution and right on the eve of World War I. The century you've lived through has been one of almost perpetual war. Do you have anything good to say about the twentieth century?

PAZ

Well, I have survived, and I think that's enough. History, you know, is one thing and our lives are something else. Our century has been terrible—one of the saddest in universal history—but our lives have always been more or less the same. Private lives are not historical. During the French or American revolutions, or during the wars between the Persians and the Greeks—during any great, universal event—history changes continually. But people live, work, fall in love, die, get sick, have friends, moments of illumination or sadness, and that has nothing to do with history. Or very little to do with it.

INTERVIEWER

So we are both in and out of history?

PAZ

Yes, history is our landscape or setting and we live through it. But the real drama, the real comedy also, is within us, and I think we can say the same for someone of the fifth century or for someone of a future century. Life is not historical, but something more like nature.

INTERVIEWER

In The Privileges of Sight, a book about your relationship with the visual arts, you say: “Neither I nor any of my friends had ever seen a Titian, a Velázquez, or a Cézanne. . . . Nevertheless, we were surrounded by many works of art.” You talk there about Mixoac, where you lived as a boy, and the art of early twentieth-century Mexico.

PAZ

Mixoac is now a rather ugly suburb of Mexico City, but when I was a child it was a small village. A very old village, from pre-Columbian times. The name Mixoac comes from the god Mixcoatl, the Nahuatl name for the Milky Way. It also means “cloud serpent,” as if the Milky Way were a serpent of clouds. We had a small pyramid, a diminutive pyramid, but a pyramid nevertheless. We also had a seventeenth-century convent. My neighborhood was called San Juan, and the parish church dated from the sixteenth century, one of the oldest in the area. There were also many eighteenth- and nineteenth-century houses, some with extensive gardens, because at the end of the nineteenth century Mixoac was a summer resort for the Mexican bourgeoisie. My family in fact had a summer house there. So when the revolution came, we were obliged, happily I think, to have to move there. We were surrounded by small memories of two pasts that remained very much alive, the pre-Columbian and the colonial.

INTERVIEWER

You talk in The Privileges of Sight about Mixoac's fireworks.

PAZ

I am very fond of fireworks. They were a part of my childhood. There was a part of the town where the artisans were all masters of the great art of fireworks. They were famous all over Mexico. To celebrate the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe, other religious festivals, and at New Year's, they made the fireworks for the town. I remember how they made the church façade look like a fiery waterfall. It was marvelous. Mixoac was alive with a kind of life that doesn't exist anymore in big cities.

INTERVIEWER

You seem nostalgic for Mixoac, yet you are one of the few Mexican writers who live right in the center of Mexico City. Soon it will be the largest city in the world, a dynamic city, but in terms of pollution, congestion, and poverty, a nightmare. Is living there an inspiration or a hindrance?

PAZ

Living in the heart of Mexico City is neither an inspiration nor an obstacle. It's a challenge. And the only way to deal with challenges is to face up to them. I've lived in other towns and cities in Mexico, but no matter how agreeable they are, they seem somehow unreal. At a certain point, my wife and I decided to move into the apartment where we live now. If you live in Mexico, you've got to live in Mexico City.

INTERVIEWER

Could you tell us something about the Paz family?

PAZ

My father was Mexican, my mother Spanish. An aunt lived with us—rather eccentric, as aunts are supposed to be, and poetic in her own absurd way. My grandfather was a lawyer and a writer, a popular novelist. As a matter of fact, during one period we lived off the sales of one of his books, a best-seller. The Mixoac house was his.