Issue 38, Summer 1966

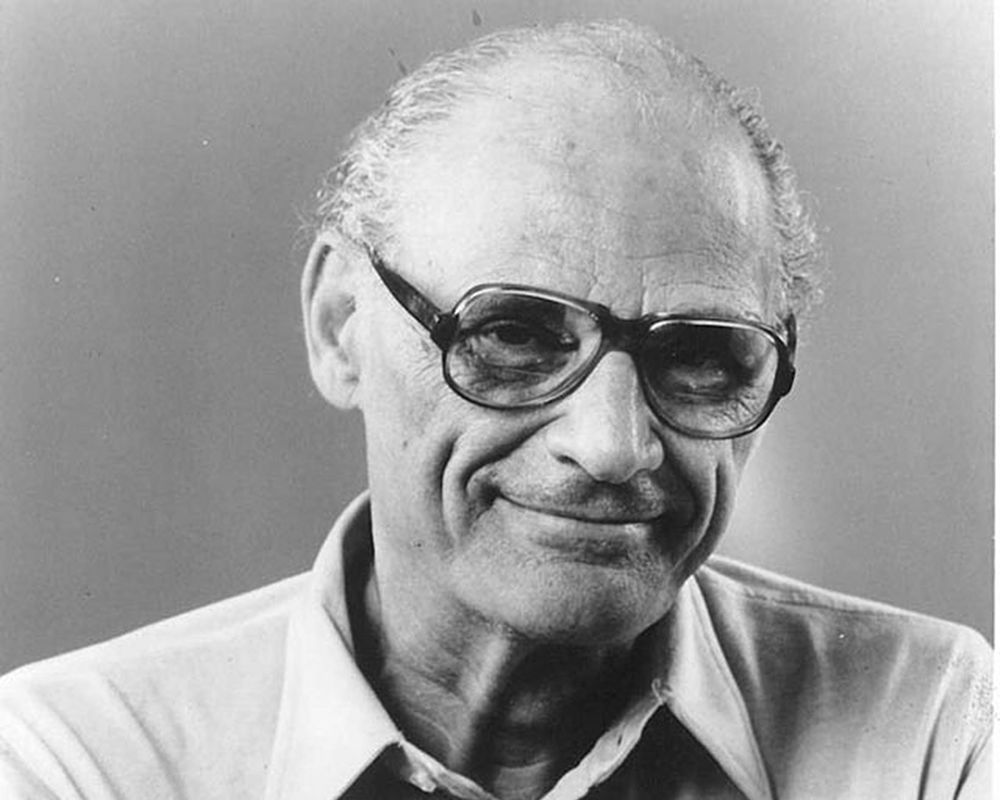

Arthur Miller.

Arthur Miller.

Arthur Miller’s white farmhouse is set high on the border of the roller-coaster hills of Roxbury and Woodbury, in Connecticut’s Litchfield County. The author, brought up in Brooklyn and Harlem, is now a county man. His house is surrounded by the trees he has raised—native dogwood, exotic katsura, Chinese scholar, tulip, and locust. Most of them were flowering as we approached his house for our interview in spring 1966. The only sound was a rhythmic hammering echoing from the other side of the hill. We walked to its source, a stately red barn, and there found the playwright, hammer in hand, standing in dim light, amid lumber, tools, and plumbing equipment. He welcomed us, a tall, rangy, good-looking man with a weathered face and sudden smile, a scholar-farmer in horn-rimmed glasses and high work shoes. He invited us in to judge his prowess: he was turning the barn into a guesthouse (partitions here, cedar closets there, shower over there … ). Carpentry, he said, was his oldest hobby—he had started at the age of five.

We walked back past the banked iris, past the hammock, and entered the house by way of the terrace, which was guarded by a suspicious basset named Hugo. Mr. Miller explained as we went in that the house was silent because his wife, photographer Inge Morath, had driven to Vermont to do a portrait of Bernard Malamud, and that their three-year-old daughter Rebecca was napping. The living room, glassed-in from the terrace, was eclectic, charming: white walls patterned with a Steinberg sketch, a splashy painting by neighbor Alexander Calder, posters of early Miller plays, photographs by Ms. Morath. It held colorful modern rugs and sofas; an antique rocker; oversized black Eames chair; a glass coffee table supporting a bright mobile; small peasant figurines—souvenirs of a recent trip to Russia—unique Mexican candlesticks, and strange pottery animals atop a very old carved Spanish table, these last from their Paris apartment; and plants, plants everywhere.

The author’s study was in total contrast. We walked up a green knoll to a spare single-roomed structure with small louvered windows. The electric light was on—he could not work by daylight, he confided. The room harbors a plain slab desk fashioned by the playwright, his chair, a rumpled gray day bed, another webbed chair from the thirties, and a bookshelf with half a dozen jacketless books. This is all, except for a snapshot of Inge and Rebecca, thumbtacked to the wall. Mr. Miller adjusted a microphone he had hung crookedly from the arm of his desk lamp. Then, quite casually, he picked up a rifle from the daybed and took a shot through the open louvers at a woodchuck that, scared but reprieved, scurried across the far slope. We were startled—he smiled at our lack of composure. He said that his study was also an excellent duck blind.

The interview began. His tone and expression were serious, interested. Often a secret grin surfaced, as he reminisced. He is a storyteller, a man with a marvelous memory, a simple man with a capacity for wonder, concerned with people and ideas. We listened at our ease at he responded to questions.

INTERVIEWER

Voznesensky, the Russian poet, said when he was here that the landscape in this part of the country reminded him of his Sigulda*—that it was a “good microclimate” for writing. Do you agree?

ARTHUR MILLER

Well, I enjoy it. It’s not such a vast landscape that you’re lost in it, and it’s not so suburban a place that you feel you might as well be in a city. The distances—internal and external—are exactly correct, I think. There’s a foreground here, no matter which way you look.

INTERVIEWER

After reading your short stories, especially “The Prophecy” and “I Don’t Need You Any More,” which have not only the dramatic power of your plays but also the description of place, the foreground, the intimacy of thought hard to achieve in a play, I wonder: is the stage much more compelling for you?

MILLER

It is only very rarely that I can feel in a short story that I’m right on top of something, as I feel when I write for the stage. I am then in the ultimate place of vision—you can’t back me up any further. Everything is inevitable, down to the last comma. In a short story, or any kind of prose, I still can’t escape the feeling of a certain arbitrary quality. Mistakes go by—people consent to them more—more than mistakes do on the stage. This may be my illusion. But there’s another matter: the whole business of my own role in my own mind. To me the great thing is to write a good play, and when I’m writing a short story it’s as though I’m saying to myself, Well, I’m only doing this because I’m not writing a play at the moment. There’s guilt connected with it. Naturally I do enjoy writing a short story; it is a form that has a certain strictness. I think I reserve for plays those things that take a kind of excruciating effort. What comes easier goes into a short story.

INTERVIEWER

Would you tell us a little about the beginning of your writing career?

MILLER

The first play I wrote was in Michigan in 1935. It was written on a spring vacation in six days. I was so young that I dared do such things, begin it and finish it in a week. I’d seen about two plays in my life, so I didn’t know how long an act was supposed to be, but across the hall there was a fellow who did the costumes for the University theater and he said, “Well, it’s roughly forty minutes.” I had written an enormous amount of material and I got an alarm clock. It was all a lark to me, and not to be taken too seriously … that’s what I told myself. As it turned out, the acts were longer than that, but the sense of the timing was in me even from the beginning, and the play had a form right from the start.

Being a playwright was always the maximum idea. I’d always felt that the theater was the most exciting and the most demanding form one could try to master. When I began to write, one assumed inevitably that one was in the mainstream that began with Aeschylus and went through about twenty-five hundred years of playwriting. There are so few masterpieces in the theater, as opposed to the other arts, that one can pretty well encompass all of them by the age of nineteen. Today, I don’t think playwrights care about history. I think they feel that it has no relevance.

INTERVIEWER

Is it just the young playwrights who feel this?

MILLER

I think the young playwrights I’ve had any chance to talk to are either ignorant of the past or they feel the old forms are too square, or too cohesive. I may be wrong, but I don’t see that the whole tragic arc of the drama has had any effect on them.

INTERVIEWER

Which playwrights did you most admire when you were young?

MILLER

Well, first the Greeks, for their magnificent form, the symmetry. Half the time I couldn’t really repeat the story because the characters in the mythology were completely blank to me. I had no background at that time to know really what was involved in these plays, but the architecture was clear. One looks at some building of the past whose use one is ignorant of, and yet it has a modernity. It had its own specific gravity. That form has never left me; I suppose it just got burned in.

INTERVIEWER

You were particularly drawn to tragedy, then?

MILLER

It seemed to me the only form there was. The rest of it was all either attempts at it, or escapes from it. But tragedy was the basic pillar.

INTERVIEWER

When Death of a Salesman opened, you said to The New York Times in an interview that the tragic feeling is evoked in us when we’re in the presence of a character who is ready to lay down his life, if need be, to secure one thing—his sense of personal dignity. Do you consider your plays modern tragedies?

MILLER

I changed my mind about it several times. I think that to make a direct or arithmetical comparison between any contemporary work and the classic tragedies is impossible because of the question of religion and power, which was taken for granted and is an a priori consideration in any classic tragedy. Like a religious ceremony, where they finally reached the objective by the sacrifice. It has to do with the community sacrificing some man whom they both adore and despise in order to reach its basic and fundamental laws and, therefore, justify its existence and feel safe.

INTERVIEWER

In After the Fall, although Maggie was “sacrificed,” the central character, Quentin, survives. Did you see him as tragic or in any degree potentially tragic?

MILLER

I can’t answer that, because I can’t, quite frankly, separate in my mind tragedy from death. In some people’s minds I know there’s no reason to put them together. I can’t break it—for one reason, and that is, to coin a phrase: there’s nothing like death. Dying isn’t like it, you know. There’s no substitute for the impact on the mind of the spectacle of death. And there is no possibility, it seems to me, of speaking of tragedy without it. Because if the total demise of the person we watch for two or three hours doesn’t occur, if he just walks away, no matter how damaged, no matter how much he suffers—

INTERVIEWER

What were those two plays you had seen before you began to write?

MILLER

When I was about twelve, I think it was, my mother took me to a theater one afternoon. We lived in Harlem and in Harlem there were two or three theaters that ran all the time, and many women would drop in for all or part of the afternoon performances. All I remember was that there were people in the hold of a ship, the stage was rocking—they actually rocked the stage—and some cannibal on the ship had a time bomb. And they were all looking for the cannibal: It was thrilling. The other one was a morality play about taking dope. Evidently there was much excitement in New York then about the Chinese and dope. The Chinese were kidnapping beautiful blond, blue-eyed girls who, people thought, had lost their bearings morally; they were flappers who drank gin and ran around with boys. And they inevitably ended up in some basement in Chinatown, where they were irretrievably lost by virtue of eating opium or smoking some pot. Those were the two masterpieces I had seen. I’d read some others, of course, by the time I started writing. I’d read Shakespeare and Ibsen, a little, not much. I never connected playwriting with our theater, even from the beginning.

INTERVIEWER

Did your first play have any bearing on All My Sons, or Death of a Salesman?

MILLER

It did. It was a play about a father owning a business in 1935, a business that was being struck, and a son being torn between his father’s interests and his sense of justice. But it turned into a near-comic play. At that stage of my life I was removed somewhat. I was not Clifford Odets; he took it head-on.