Issue 69, Spring 1977

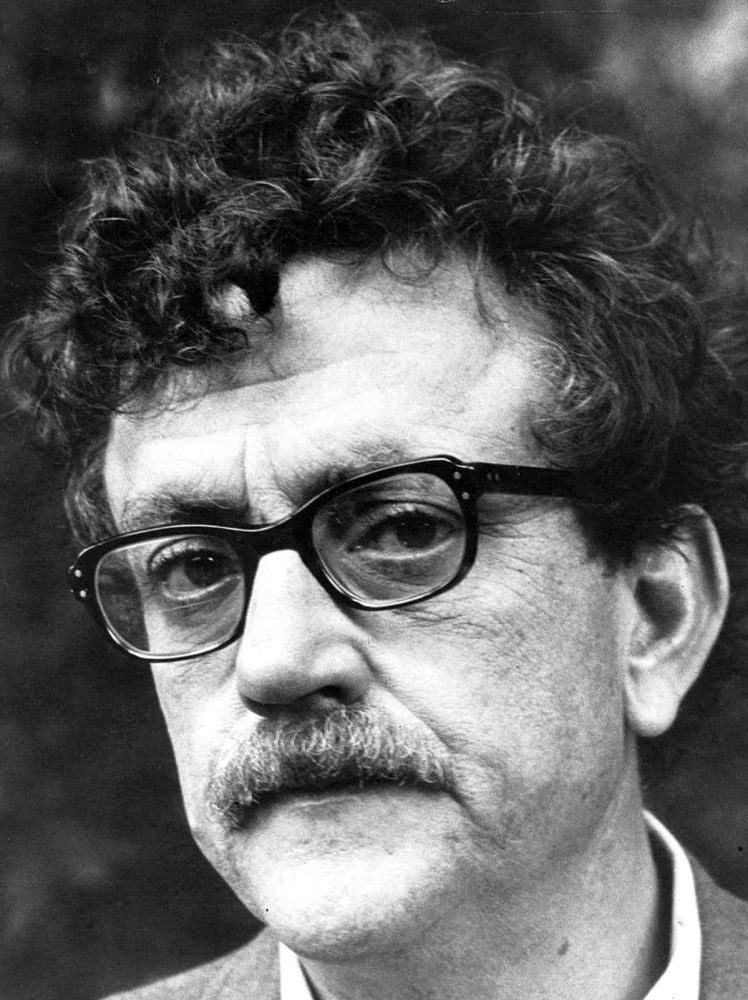

Kurt Vonnegut, ca. 1972. Photograph by PBS

Kurt Vonnegut, ca. 1972. Photograph by PBS

This interview with Kurt Vonnegut was originally a composite of four interviews done with the author over the past decade. The composite has gone through an extensive working over by the subject himself, who looks upon his own spoken words on the page with considerable misgivings . . . indeed, what follows can be considered an interview conducted with himself, by himself.

The introduction to the first of the incorporated interviews (done in West Barnstable, Massachusetts, when Vonnegut was forty-four) reads: “He is a veteran and a family man, large-boned, loose-jointed, at ease. He camps in an armchair in a shaggy tweed jacket, Cambridge gray flannels, a blue Brooks Brothers shirt, slouched down, his hands stuffed into his pockets. He shells the interview with explosive coughs and sneezes, windages of an autumn cold and a lifetime of heavy cigarette smoking. His voice is a resonant baritone, Midwestern, wry in its inflections. From time to time he issues the open, alert smile of a man who has seen and reserved within himself almost everything: depression, war, the possibility of violent death, the inanities of corporate public relations, six children, an irregular income, long-delayed recognition.

The last of the interviews that made up the composite was conducted during the summer of 1976, years after the first. The description of him at this time reads: “ . . . he moves with the low-keyed amiability of an old family dog. In general, his appearance is tousled: the long curly hair, mustache, and sympathetic smile suggest a man at once amused and saddened by the world around him. He has rented the Gerald Murphy house for the summer. He works in the little bedroom at the end of a hall where Murphy, artist, bon vivant, and friend to the artistic great, died in 1964. From his desk Vonnegut can look out onto the front lawn through a small window; behind him is a large, white canopy bed. On the desk next to the typewriter is a copy of Andy Warhol’s Interview, Clancy Sigal’s Zone of the Interior, and several discarded cigarette packs.

“Vonnegut has chain-smoked Pall Malls since 1936 and during the course of the interview he smokes the better part of one pack. His voice is low and gravelly, and as he speaks, the incessant procedure of lighting the cigarettes and exhaling smoke is like punctuation in his conversation. Other distractions, such as the jangle of the telephone and the barking of a small, shaggy dog named Pumpkin, do not detract from Vonnegut’s good-natured disposition. Indeed, as Dan Wakefield once said of his fellow Shortridge High School alumnus, ‘He laughed a lot and was kind to everyone.’“

INTERVIEWER

You are a veteran of the Second World War?

VONNEGUT

Yes. I want a military funeral when I die—the bugler, the flag on the casket, the ceremonial firing squad, the hallowed ground.

INTERVIEWER

Why?

VONNEGUT

It will be a way of achieving what I’ve always wanted more than anything—something I could have had, if only I’d managed to get myself killed in the war.

INTERVIEWER

Which is—?

VONNEGUT

The unqualified approval of my community.

INTERVIEWER

You don’t feel that you have that now?

VONNEGUT

My relatives say that they are glad I’m rich, but that they simply cannot read me.

INTERVIEWER

You were an infantry battalion scout in the war?

VONNEGUT

Yes, but I took my basic training on the 240-millimeter howitzer.

INTERVIEWER

A rather large weapon.

VONNEGUT

The largest mobile fieldpiece in the army at that time. This weapon came in six pieces, each piece dragged wallowingly by a Caterpillar tractor. Whenever we were told to fire it, we had to build it first. We practically had to invent it. We lowered one piece on top of another, using cranes and jacks. The shell itself was about nine and a half inches in diameter and weighed three hundred pounds. We constructed a miniature railway which would allow us to deliver the shell from the ground to the breech, which was about eight feet above grade. The breechblock was like the door on the vault of a savings and loan association in Peru, Indiana, say.

INTERVIEWER

It must have been a thrill to fire such a weapon.

VONNEGUT

Not really. We would put the shell in there, and then we would throw in bags of very slow and patient explosives. They were damp dog biscuits, I think. We would close the breech, and then trip a hammer which hit a fulminate of mercury percussion cap, which spit fire at the damp dog biscuits. The main idea, I think, was to generate steam. After a while, we could hear these cooking sounds. It was a lot like cooking a turkey. In utter safety, I think, we could have opened the breechblock from time to time, and basted the shell. Eventually, though, the howitzer always got restless. And finally it would heave back on its recoil mechanism, and it would have to expectorate the shell. The shell would come floating out like the Goodyear blimp. If we had had a stepladder, we could have painted “Fuck Hitler” on the shell as it left the gun. Helicopters could have taken after it and shot it down.

INTERVIEWER

The ultimate terror weapon.

VONNEGUT

Of the Franco-Prussian War.