Issue 74, Fall-Winter 1978

Margaret Drabble lives in a red house along a row of terrace houses just up the hill from Hampstead Heath. Her sitting room is also red—bright red—and stretches from the front bay windows, which are filled with plants to a large back window that looks out onto the garden. Along one wall there are floor-to-ceiling bookshelves and in one corner there is a baby grand. On top of the piano sits a plant that was given to the author by Doris Lessing. “I don't know what Doris's plant is called. I call it a funnel plant because it has a kind of funnel down which one waters it. Once, it had a big pink bottle brush flower, but I think it never will again.”

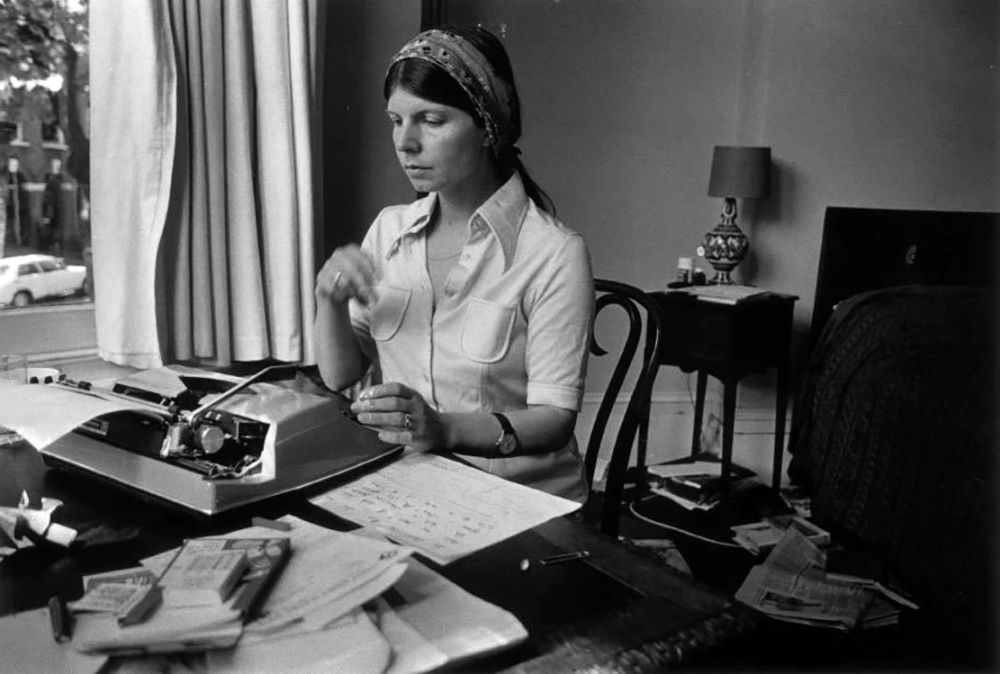

In front of the room there is a fireplace with a shiny white mantelpiece. Two ceramic pitchers of bushy dried grasses stand on either side of a gilded mirror and next to them lie pictures and statues and boxes and one large pinecone. Across from the fireplace, several shopping bags lean against one another in the leg space beneath a small desk. It is too small and fine a desk for novel-writing. Drabble writes her books in a room in Bloomsbury.

On the walls there are several paintings. One is gray and geometric: an open door leading from an empty corridor into an empty room. Another is a still life of a table laden with fruit.

Behind Drabble's house, backyards connecting, is the house where John Keats lived. It is a two-story house with many tiny rooms. “They were smaller in those days,” said the lady behind the information desk. “They called him little Johnny Keats.”

Margaret Drabble is called “Maggie,” and she, too, is smaller than one might expect from looking at her photographs. Her face is finer, prettier and younger, surprisingly young for someone who has produced so many books in the past sixteen years. Her eyes are very clear and attentive and they soften when she is amused, as she often is, by the questions themselves and her own train of thought.

INTERVIEWER

Are there any questions you are afraid of being asked?

MARGARET DRABBLE

No, because I am very good at not answering them. I don't much like being nagged about my private life because it involves others than myself, and I haven't got a right to speak for them. But most people are very conscious of this and don't nag. I don't like placing other writers much and avoid the temptation to do so when asked, though I don't mind admitting my immense admiration for Angus Wilson, Saul Bellow, and Doris Lessing.

INTERVIEWER

I know you've done your share of interviewing. What is the first question you ask someone?

DRABBLE

Oh dear. I never know how to begin. I find it to be a very difficult job, actually. I'm rather a bad interviewer because I never ask people things that they don't want to be asked. As soon as they look annoyed or nervous, I never persist.

INTERVIEWER

I read your interview with Doris Lessing and I thought that many of the things that came out of it could have been said about you as well. You quote her as saying, “In writing novels, we bring into being what we need to be.” Can you comment on that?

DRABBLE

In a sense, the fiction creates the reality, but it's a very complicated relationship. I think if you imagine a certain kind of person, then that person comes into being. You become that person. Or at least this kind of person becomes a possibility. But you have to be careful what you imagine, because the act of imagining is the act of encouraging yourself to be a certain kind of person. The fact of going in a certain direction has something to do with what you imagine as good or proper for yourself.

INTERVIEWER

But it also seems to me, that as far as you're concerned, the kind of person you are has as much to do with fate or accident as it does with self-creation.

DRABBLE

This is what is so interesting about life: choosing to be something and being struck down while you do it by a falling brick. The whole question of free will and choice and determinism is inevitably interesting to a novelist. Perhaps I go on about it more than some. Are your characters puppets in the hands of fate or are they really able to make free choices? I think we have a very small area of free choice.

INTERVIEWER

And what is that area?

DRABBLE

We can choose not to be selfish or as self-indulgent or as hard-working as we are by nature. We can choose to go against our nature, but only very slightly. You can't completely alter what you were given without doing yourself a great violence, which means that you go mad or become an ineffective person. It also has to do with where you start from. You can't ignore it or cut it out of yourself. I think families change over the generations, but the amount that each person changes is not as great as he thinks it's going to be when he is young.

INTERVIEWER

Was it an accident that you became a writer?

DRABBLE

I wrote my first novel because I just got married and I was living in Stratford-upon-Avon and there was nothing else to do. I was very bored. I had no particular friends there. I'd been very busy up until then—at university, passing examinations—I very nearly took a job that summer and if I had taken a job, I probably wouldn't have written the book. So in a sense it was accidental. Whether I would have written a novel later, I just don't know.

INTERVIEWER

What did you study at Cambridge?

DRABBLE

English Literature. I got a very good degree. I got a husband, but he was an actor, and worked long hours. At the time, I very much wanted to be an actress and in fact I did act for a year, but by then I had my first novel accepted. I was still very keen on the stage but I was losing interest in it because of the children—I had one and was expecting another—and writing was such a convenient career to combine with having a family. Also I had quite a considerable success with my first novel, so I was encouraged to continue.

INTERVIEWER

Where did the idea for your first novel come from?

DRABBLE

I think it must have been related to my feelings at finding myself, at the age of twenty-one, free, unemployed, wondering where to go, watching my friends and contemporaries to see where they would go. Perhaps it was about the purpose of education for women and the choices it offers.