Issue 134, Spring 1995

Ted Hughes lives with his wife, Carol, on a farm in Devonshire. It is a working farm—sheep and cows—and the Hugheses are known to leave a party early to tend to them. “Carol’s got to get the sheep in,” Hughes will explain.

He came to London for the interview, which took place in the interviewer’s dining room. The poet was wearing a tweed jacket, dark trousers, and a tie whose predominantly blue color matched his eyes. His voice is commanding. He is often invited to read his work, the flow of his language enlivening the text. In appearance he is impressive, and yet there is very little aggression or intimidation in his look. Indeed, one admirer has said that her first thought sitting opposite him was that this was what God should look like “when you get there.”

Born Edward James Hughes on August 17, 1930 in the small mill town of Mytholmroyd, he is the youngest of the three children of Edith Farrar Hughes and William Henry Hughes. The first seven years of his life were spent in West Yorkshire, on that area’s barren, windswept moors. Hughes once said that he could “never escape the impression that the whole region [was] in mourning for the First World War.”

He began to write poetry at age seven, after his family moved to Mexborough. It was under the tutelage of his teacher at the town’s only grammar school that Hughes began to mature—his work evolving into the rhythmic passionate poetry for which he has become known throughout the world.

Following two years of service in the Royal Air Force, Hughes enrolled at Pembroke College, Cambridge University. He had initially intended to study English literature but found that department’s curriculum too limited; archeology and anthropology proved to be areas of the academic arena more suited to his taste.

Two years after graduating, Hughes and a group of classmates founded the infamous literary magazine St. Botolph’s Review—known more for its inaugural party than its longevity (it lasted only one issue). It was at that party that Hughes met Sylvia Plath, an American student studying in England. Plath would recall the event in a journal entry: “I met the strongest man in the world, ex-Cambridge, brilliant poet whose work I loved before I met him, a large, bulky, healthy Adam, half French, half Irish, with a voice like the thunder of god—a singer, story-teller, lion, and world wanderer, a vagabond who will never stop.” They were wed on June 16, 1956 and remained married for six and a half years, having two children, Frieda and Nicholas. In the fall of 1962 they became estranged over Hughes’s alleged infidelities. On February 11, 1963, while residing in a separate apartment, Plath placed towels under the door of the room where her children were napping, laid out a snack for them, turned on the gas jet of her kitchen stove and placed her head in the oven—asphyxiating herself.

A few months after their marriage Plath had entered a number of her husband’s poems in a competition judged by W. H. Auden, among others. Hughes was awarded first prize for his collection Hawk in the Rain. It was published in 1957 by Faber & Faber in England and Harper & Row in America. With his next publication, Lupercal, in 1960, Hughes became recognized as one of the most significant English poets to emerge since World War II, winning the Somerset Maugham Award in 1960 and the Hawthornden Prize in 1961.

His next notable work was Wadwo, a compilation of five short stories, a radio play, and some forty poems. Although it contained many of the violent animal images of Hughes’s earlier work, it reflected the poet’s growing enchantment with mythology. Wadwo led Hughes into an odd fascination with one of the most solitary and ominous images in folklore, the crow. While his aspiration to create an epic tale centering on this bird has not been fulfilled, he did publish Crow: From the Life and Songs of the Crow in 1970, sixty-six poems or “songs,” as Hughes referred to them. The American version, published by Harper the following year, was well received. The New York Review of Books said that Crow was “perhaps a more plausible explanation for the present condition of the world than the Christian sequence.”

Still deeply interested in mythology and folklore, Hughes created Orghast, a play based largely on the Prometheus legend, in 1971, while he was in Iran with members of the International Center for Theater Research. He wrote most of the play’s dialogue in an invented language to illustrate the theory that sound alone could express very complex human emotions. Hughes continued on this theme with his next work of poetry entitled Prometheus on His Crag, published in 1973 by Rainbow Press.

His next two works of note, Cave Birds and Gaudete, were predominantly based on the Gravesian concept that mankind has sinned by denying the “White Goddess,” the natural, primordial aspect of modern man, while choosing to nurture a conscious, almost sterile intellectual humanism.

Following the publication of his 1983 work River, Ted Hughes was named poet laureate of Great Britain. His recent publications, Flowers and Insects (1987) and Wolfwatching (1991), show a return to his earlier nature-oriented work—possessing a raw force that evokes the physical immediacy of human experience.

Hughes has shown a great range in his work, and aside from his adult verse, he has written children’s stories (Tales of the Early World), poetry (Under the North Star) and plays (The Coming of the Kings). Hughes has also edited selections of other writers’ work, most notably the late Plath’s. The controversy surrounding Hughes’s notorious editing and reordering of Plath’s poetry and journals, the destruction of at least one volume of the latter, as well as the mysterious disappearance of her putative final novel have mythologized both poets and made it difficult for Hughes to live the anonymous life he has sought in rural Devonshire.

INTERVIEWER

Would you like to talk about your childhood? What shaped your work and contributed to your development as a poet?

TED HUGHES

Well, as far as my writing is concerned, maybe the crucial thing was that I spent my first years in a valley in West Yorkshire in the north of England, which was really a long street of industrial towns—textile mills, textile factories. The little village where I was born had quite a few; the next town fifty. And so on. These towns were surrounded by a very wide landscape of high moorland, in contrast to that industry into which everybody disappeared everyday. They just vanished. If you weren’t at school you were alone in an empty wilderness.

When I came to consciousness my whole interest was in wild animals. My earliest memories are of the lead animal toys you could buy in those days, wonderfully accurate models. Throughout my childhood I collected these. I had a brother, ten years older, whose passion was shooting. He wanted to be a big game hunter or a game warden in Africa—that was his dream. His compromise in West Yorkshire was to shoot over the hillsides and on the moor edge with a rifle. He would take me along. So my early memories of being three and four are of going off with him, being his retriever. I became completely preoccupied by his world of hunting. He was also a very imaginative fellow; he mythologized his hunting world as North American Indian, paleolithic. And I lived in his dream. Up to the age of seventeen or eighteen, shooting and fishing and my preoccupation with animals were pretty well my life, apart from books. That makes me sound like more of a loner than I was. Up to twelve or thirteen I also played with my town friends every evening, a little gang, the innocent stuff of those days, kicking about the neighborhood. But weekends I was off on my own. I had a double life.

The writing, the reading came up gradually behind that. From the age of about eight or nine I read just about every comic book available in England. At that time my parents owned a newsagent’s shop. I took the comics from the shop, read them, and put them back. That went on until I was twelve or thirteen. Then my mother brought in a sort of children’s encyclopedia that included sections of folklore. Little folktales. I remember the shock of reading those stories. I could not believe that such wonderful things existed. The only stories we’d had as younger children were ones our mother had told us—that she made up, mostly. In those early days ours wasn’t a house full of books. My father knew quite long passages of “Hiawatha” that he used to recite, something he had from his school days. That had its effect. I remember I wrote a good deal of comic verse for classroom consumption in Hiawatha meter. But throughout your life you have certain literary shocks, and the folktales were my first. From then on I began to collect folklore, folk stories, and mythology. That became my craze.

INTERVIEWER

Can you remember when you first started writing?

HUGHES

I first started writing those comic verses when I was eleven, when I went to grammar school. I realized that certain things I wrote amused my teacher and my classmates. I began to regard myself as a writer, writing as my specialty. But nothing more than that until I was about fourteen, when I discovered Kipling’s poems. I was completely bowled over by the rhythm. Their rhythmical, mechanical drive got into me. So suddenly I began to write rhythmical poems, long sagas in Kiplingesque rhythms. I started showing them to my English teacher—at the time a young woman in her early twenties, very keen on poetry. I suppose I was fourteen, fifteen. I was sensitive, of course, to any bit of recognition of anything in my writing. I remember her—probably groping to say something encouraging—pointing to one phrase saying, This is really . . . interesting. Then she said, It’s real poetry. It wasn’t a phrase; it was a compound epithet concerning the hammer of a punt gun on an imaginary wildfowling hunt. I immediately pricked up my ears. That moment still seems the crucial one. Suddenly I became interested in producing more of that kind of thing. Her words somehow directed me to the main pleasure in my own life, the kind of experience I lived for. So I homed in. Then very quickly—you know how fast these things happen at that age—I began to think, Well, maybe this is what I want to do. And by the time I was sixteen that was all I wanted to do.

I equipped myself in the most obvious way: whatever I liked I tried to learn by heart. I imitated things. And I read a great deal aloud to myself. Reading verse aloud put me on a kind of high. Gradually all this replaced shooting and fishing. When my shooting pal went off to do his national service, I used to sit around in the woods, muttering through my books. I read the whole of The Faerie Queene like that. All of Milton. Lots more. It became sort of a hobby-habit. I read a good deal else as well and was constantly trying to write something, of course. That same teacher lent me her Eliot and introduced me to three or four of Hopkins’s poems. Then I met Yeats. I was still preoccupied by Kipling when I met Yeats via the third part of his poem “The Wandering of Oisin,” which was in the kind of meter I was looking for. Yeats sucked me in through the Irish folklore and myth and the occult business. My dominant passion in poetry up to and through university was Yeats, Yeats under the canopy of Shakespeare and Blake. By the time I got to university, at twenty-one, my sacred canon was fixed: Chaucer, Shakespeare, Marlowe, Blake, Wordsworth, Keats, Coleridge, Hopkins, Yeats, Eliot. I knew no American poetry at all except Eliot. I had a complete Whitman but still didn’t know how to read it. The only modern foreign poet I knew was Rilke in Spender’s and Leishmann’s translation. I was fascinated by Rilke. I had one or two collections with me through my national service. I could see the huge worlds of other possibilities opening in there. But I couldn’t see how to get into them. I also had my mother’s Bible, a small book with the psalms, Jeremiah, the Song of Songs, Proverbs, Job, and other bits here and there all set out as free verse. I read whatever contemporary verse I happened to come across, but apart from Dylan Thomas and Auden, I rejected it. It didn’t give me any leads somehow, or maybe I simply wasn’t ready for it.

INTERVIEWER

Was it difficult to make a living when you started out? How did you do it?

HUGHES

I was ready to do anything, really. Any small job. I went to the U.S. and taught a little bit, though I didn’t want to. I taught first in England in a secondary school, fourteen-year-old boys. I experienced the terrific exhaustion of that profession. I wanted to keep my energy for myself, as if I had the right. I found teaching fascinating but wanted too much to do something else. Then I saw how much money could be made quite quickly by writing children’s books. A story—perhaps not true—is that Maxine Kumin wrote fifteen children’s stories and made a thousand dollars for each. That seemed to me preferable to attempting a big novel or a problematic play, which would devour great stretches of time with doubtful results in cash. Also, it seemed to me I had a knack of a kind for inventing children’s stories. So I did write quite a few. But I didn’t have Maxine Kumin’s magic. I couldn’t sell any of them. I sold them only years later, after my verse had made a reputation for me of a kind. So up to the age of thirty-three, I was living on what one lives on: reviews, BBC work, little radio plays, that sort of thing. Anything for immediate cash. Then, when I was thirty-three, I suddenly received in the post the news that the Abraham Woursell Foundation had given me a lecturer’s salary at the University of Vienna for five years. I had no idea how I came to be awarded this. That salary took me from thirty-four years old to thirty-eight, and by that time I was earning my living by my writing. A critical five years. That was when I had the children, and the money saved me from looking for a job outside the house.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a favorite place to write or can you write anywhere?

HUGHES

Hotel rooms are good. Railway compartments are good. I’ve had several huts of one sort or another. Ever since I began to write with a purpose I’ve been looking for the ideal place. I think most writers go through it. I’ve known several who liked to treat it as a job—writing in some office well away from home, going there regular hours. Sylvia had a friend, a novelist, who used to leave her grand house and go into downtown Boston to a tiny room with a table and chair where she wrote facing a blank wall. Didn’t Somerset Maugham also write facing a blank wall? Subtle distraction is the enemy—a big beautiful view, the tide going in and out. Of course, you think it oughtn’t to matter, and sometimes it doesn’t. Several of my favorite pieces in my book Crow I wrote traveling up and down Germany with a woman and small child—I just went on writing wherever we were. Enoch Powell claims that noise and bustle help him to concentrate. Then again, Goethe couldn’t write a line if there was another person anywhere in the same house, or so he said at some point. I’ve tried to test it on myself, and my feeling is that your sense of being concentrated can deceive you. Writing in what seems to be a happy concentrated way, in a room in your own house with books and everything necessary to your life around you, produces something noticeably different, I think, from writing in some empty silent place far away from all that. Because however we concentrate, we remain aware at some level of everything around us. Fast asleep, we keep track of the time to the second. The person conversing at one end of a long table quite unconsciously uses the same unusual words, within a second or two, as the person conversing with somebody else at the other end—though they’re amazed to learn they’ve done it. Also, different kinds of writing need different kinds of concentration. Goethe, picking up a transmission from the other side of his mind, from beyond his usual mind, needs different tuning than Enoch Powell when he writes a speech. Brain rhythms would show us what’s going on, I expect. But for me successful writing has usually been a case of having found good conditions for real, effortless concentration. When I was living in Boston, in my late twenties, I was so conscious of this that at one point I covered the windows with brown paper to blank out any view and wore earplugs—simply to isolate myself from distraction. That’s how I worked for a year. When I came back to England, I think the best place I found in that first year or two was a tiny cubicle at the top of the stairs that was no bigger than a table really. But it was a wonderful place to write. I mean, I can see now, by what I wrote there, that it was a good place. At the time it just seemed like a convenient place.

INTERVIEWER

What tools do you require?

HUGHES

Just a pen.

INTERVIEWER

Just a pen? You write longhand?

HUGHES

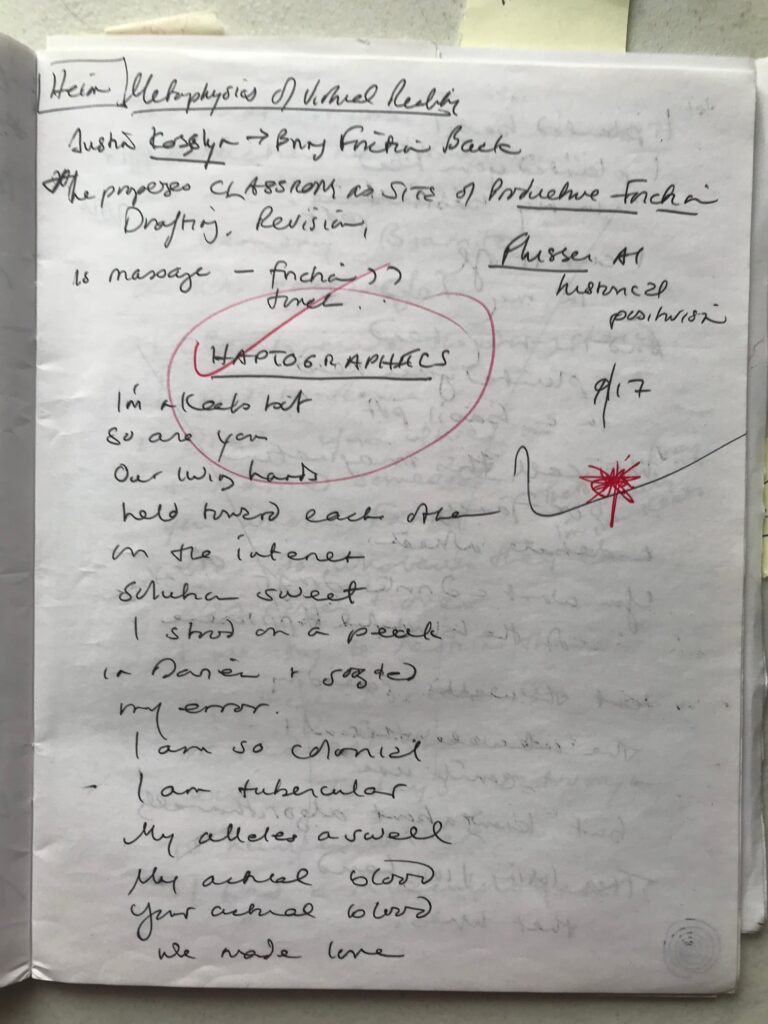

I made an interesting discovery about myself when I first worked for a film company. I had to write brief summaries of novels and plays to give the directors some idea of their film potential—a page or so of prose about each book or play and then my comment. That was where I began to write for the first time directly onto a typewriter. I was then about twenty-five. I realized instantly that when I composed directly onto the typewriter my sentences became three times as long, much longer. My subordinate clauses flowered and multiplied and ramified away down the length of the page, all much more eloquently than anything I would have written by hand. Recently I made another similar discovery. For about thirty years I’ve been on the judging panel of the W. H. Smith children’s writing competition. Annually there are about sixty thousand entries. These are cut down to about eight hundred. Among these our panel finds seventy prizewinners. Usually the entries are a page, two pages, three pages. That’s been the norm. Just a poem or a bit of prose, a little longer. But in the early 1980s we suddenly began to get seventy- and eighty-page works. These were usually space fiction, always very inventive and always extraordinarily fluent—a definite impression of a command of words and prose, but without exception strangely boring. It was almost impossible to read them through. After two or three years, as these became more numerous, we realized that this was a new thing. So we inquired. It turned out that these were pieces that children had composed on word processors. What’s happening is that as the actual tools for getting words onto the page become more flexible and externalized, the writer can get down almost every thought or every extension of thought. That ought to be an advantage. But in fact, in all these cases, it just extends everything slightly too much. Every sentence is too long. Everything is taken a bit too far, too attenuated. There’s always a bit too much there, and it’s too thin. Whereas when writing by hand you meet the terrible resistance of what happened your first year at it when you couldn’t write at all . . . when you were making attempts, pretending to form letters. These ancient feelings are there, wanting to be expressed. When you sit with your pen, every year of your life is right there, wired into the communication between your brain and your writing hand. There is a natural characteristic resistance that produces a certain kind of result analogous to your actual handwriting. As you force your expression against that built-in resistance, things become automatically more compressed, more summary and, perhaps, psychologically denser. I suppose if you use a word processor and deliberately prune everything back, alert to the tendencies, it should be possible to get the best of both worlds.

Maybe what I’m saying applies only to those who have gone through the long conditioning of writing only with a pen or pencil up through their mid-twenties. For those who start early on a typewriter or, these days, on a computer screen, things must be different. The wiring must be different. In handwriting the brain is mediated by the drawing hand, in typewriting by the fingers hitting the keyboard, in dictation by the idea of a vocal style, in word processing by touching the keyboard and by the screen’s feedback. The fact seems to be that each of these methods produces a different syntactic result from the same brain. Maybe the crucial element in handwriting is that the hand is simultaneously drawing. I know I’m very conscious of hidden imagery in handwriting—a subtext of a rudimentary picture language. Perhaps that tends to enforce more cooperation from the other side of the brain. And perhaps that extra load of right brain suggestions prompts a different succession of words and ideas. Perhaps that’s what I am talking about.