What’s in our Fall issue? Interviews with comics creator Chris Ware and novelists Herta Müller and Aharon Appelfeld; letters between George Plimpton and Terry Southern; fiction by Alejandro Zambra, David Gates, and Atticus Lish; poetry by Karen Solie and Ben Lerner; an essay by David Searcy; and the final installment of a novel by Rachel Cusk. And we haven’t even put the issue to bed yet!

Enjoy the preview below—and subscribe today to receive a full year of The Paris Review.

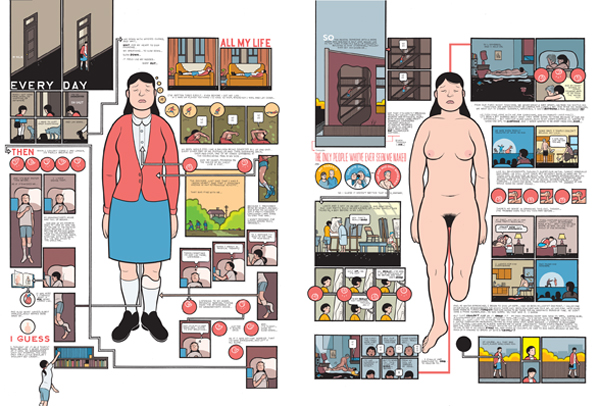

Credit: Chris Ware, from Building Stories.

___________________________________________________________

Chris Ware, The Art of Comics No. 2

A book can be something of a metaphor for the human body—it has a face that can reveal itself or lie, it has a spine, it’s bigger on the inside than it is on the outside. The layering of panels and pages and chapters essentially makes a sculpture in space and in the memory of the reader. I also think there’s a certain poetic harmony between the physicality of a book and the ineffability of what it contains, like our bodies with our child selves somewhere buried alive inside, to say nothing of what we think of as consciousness somewhere in there as well.

One of the reasons I stayed interested in comics was their potential for getting at the four-dimensional shape of existence and a lot of my lame undergraduate stuff—pedantic panel-crossing characters, spinning chairs in space—was a sort of unremarkable self-conscious fooling around with all that, which has had a lingering taint on how I think of the page, book, etcetera, as a “perpetually existing” sort of shape that only comes alive when read. The best comics make drawings seem to come alive on the page and make the visual connections between moments across pages and even chapters concretely explicit, which is a very different experience from looking page after page of gray text. Not to carry this too far, but unlike regular reading, which induces blindness in the reader, comics bring together the half-awake “night and day” of seeing and remembering directly on the page.

___________________________________________________________

Long Distance

Alejandro Zambra

One night, at the beginning of class, one student raised his hand and told me that he wanted to write a letter of resignation, because he was planning to quit his job. He started talking, then, about the problems he had with his boss; I tried to give him advice, but I was possibly the least qualified person in the room to do that. Someone told him he was irresponsible, that before quitting he should think about how he was going to live and how he would pay for school. A weighty and serious silence followed, which I didnʼt know how to fill.

“I want to write the letter,” he told us then. “Iʼm not going to quit, I couldnʼt, I have kids, I have problems, but I still want to write that letter. I want to imagine what it would be like to quit. I want to tell my boss how I really feel about him. I want to tell him heʼs a son of a bitch, but without using that word.”

“Itʼs not a word, itʼs several,” said a student sitting in the first row.

___________________________________________________________

Jimmy

Atticus Lish

Rikers could make you deaf. For weeks after his release, he shouted. It turned his volume up. He somehow found himself in exchanges with other men on the subway or on the street who had passed through the jail as well. They found each other by the way they spoke out in public, in the line outside the unmarked entrance in Ozone Park where Jimmy waited with the other offenders wearing sweatshirts over their heads and blowing vapor in the cold, shuffling upstairs to give his number and get his pills.

On the corner, wind-burned, dull-eyed, they said, Oh, you a union man. There’s a pride, Jimmy said. You got it made, they said. All you gotta do is keep tight. Keep it in tight! they laughed. They lived in a shelter off Centre Street and did temporary work unloading trucks for Chinese merchants who owned lighting businesses on Bowery.

When I got out after five years I would do any job, a Puerto Rican named Cat said. My sentence was for murder. I served my time, I don’t care. It happened because I was seeing a woman. She was Dominican. Highly attractive to men. Everybody noticed me with her. This guy, he was a big dude, he liked her and he kept trying to pursue an interest in her. I went to talk to him. He broke my nose, hurt my pride. I came back and knocked on the door. She come out and I said get Jose, and as soon as he come, I had a butcher knife. I jumped on him and kept stabbing him. They gave me murder. When I served my time, I used to jump rope, go for a jog, anything to forget the time.