Issue 217, Summer 2016

Few novels stand for a place and time the way Bright Lights, Big City stands for downtown Manhattan in the 1980s. Narrated in the second person, Jay McInerney’s first novel tells the story of a young fact-checker, at a magazine very much like The New Yorker, who loses his way in the cocaine-fueled nightclub scene. From the moment it appeared as a paperback original, in 1984, Bright Lights established McInerney as a chronicler of New York’s bright young things. In his six subsequent novels and numerous short stories, he has broadened his scope and his canvas, but he has never taken his eye off his adoptive city or the intersection of the literary world and that city’s flashier precincts. His recently completed novel, Bright, Precious Days, is the third in a trilogy that follows the fortunes of book editor Russell Calloway and his wife, Corrine, as they struggle and thrive from the late 1980s through the 2008 recession.

Born in 1955, McInerney spent his childhood moving from suburb to suburb in the U.S., Canada, and England. His father was an executive for a New England paper company and, in McInerney’s words, a “Nixon guy.” His mother, a housewife, was active in liberal charities. (There is a children’s center in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, named in her honor.) Sharing her political passions, her son, a “would-be hippie,” was drawn toward social activism at Williams College, then as now filled with investment bankers in training. In 1977, after a stint as a local reporter in New Jersey, McInerney received a fellowship to teach in Japan, where he hoped to write the Great American Expat Novel in the style of Robert Stone or Graham Greene. Notes in hand, he returned to the U.S. three years later with his first wife and took a short-lived job as a fact-checker at The New Yorker. But he made his first mark on the literary world with a story in the Winter 1982 issue of The Paris Review, which would become the first chapter of Bright Lights.

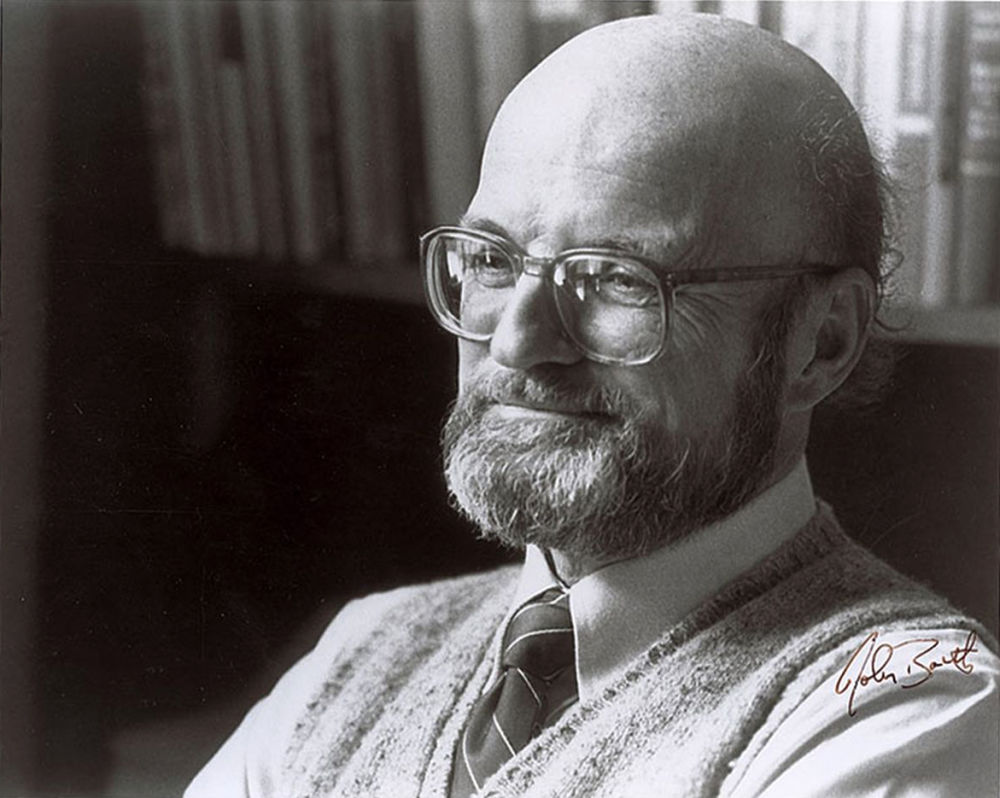

I spoke with McInerney three times in February and March of this year. We met in the Greenwich Village apartment he shares with his fourth wife, Anne Hearst McInerney. Their art collection dates from the moment they each arrived in New York: works by Cindy Sherman, Keith Haring, and Caio Fonseca share wall space with photographs of McInerney’s literary heroes Faulkner, Joyce, and Kerouac. Once we turned off the recorder, our conversations continued over a meal in the neighborhood and a bottle or two of very good wine (since 1996, McInerney has moonlighted as a wine critic for House & Garden, the Wall Street Journal, and Town & Country). He is known, and much appreciated, for bringing his own hamper of bottles to black-tie benefits around New York.

Now sixty-one, McInerney has lost none of the energetic volubility that made him one of the most quoted writers of the mideighties, when he, Bret Easton Ellis, and Tama Janowitz were collectively known, by critics and gossip columnists alike, as the “Brat Pack.” Although he enjoys telling a good story—especially if it shows him in a slightly comical light—it is notable how often our talk turned to other people’s fiction, either the classics that formed his sensibility or new novels that piqued his interest. (Janice Y. K. Lee’s The Expatriates was on the breakfast table.)

—Lucas Wittmann

INTERVIEWER

When did you decide you wanted to be a writer?

MCINERNEY

In eighth grade, when I first read Dylan Thomas. His is a kind of poetry designed to appeal to the adolescent mind more than T. S. Eliot’s, perhaps. I found him intoxicating. I quickly devoured all of his poetry, and then I started looking elsewhere for something like it. In high school, I found my way back to the modernists—Eliot and Pound—and forward to the Robert Lowell and John Berryman generation. At some point, I started telling people that I was going to be a poet, which of course broke my father’s heart, and my grandfather’s as well. They didn’t think it was a manly profession. Or a lucrative one. But I didn’t really think of writing fiction until I was in my junior year at Williams College. I took a course on Ulysses. We read Portrait of the Artist and Dubliners as well. I realized that prose could be linguistically as intricate and challenging as poetry.

INTERVIEWER

After college you got a fellowship in Japan. What were you doing there?

MCINERNEY

I wanted to write the Great Expatriate Novel, and it didn’t seem like Paris was the place to go anymore. I decided that perhaps Japan was. And Woodward and Bernstein had made it almost impossible to find a good newspaper gig. My roommate at Williams was already there and I managed to land this Princeton teaching fellowship. So off I went. Then I ended up getting excited about Japanese culture. I studied the language. I studied karate. I studied Zen. After the fellowship, which was six months teaching English in a place called Fujinomiya, I moved to Kyoto, the ancient capital, the center of Japanese culture.

INTERVIEWER

What was your life there like?

MCINERNEY

I was alone for the first year, and then I met my future wife. In a bar, actually. She had come over from Seattle to model. There was a big market for American models at the time, though actually she was half Japanese. Her father was a soldier who’d been stationed in Tokyo and had married a Japanese woman. So she was returning to her roots, in a way. We lived together and eventually moved to New York at the end of ’79.

INTERVIEWER

Why did you want to live in New York?

MCINERNEY

It was an interesting time to arrive here, that moment where it still seemed as if the city could go either way. It had almost gone bankrupt in ’77. White people were still fleeing to the suburbs. There was a heroin epidemic. The city was still dirty and dangerous. At the same time, there was this interesting cultural scene, the music coming out of the Lower East Side, CBGB, and Max’s Kansas City. I felt like there should be a literary equivalent to all of that. A literary equivalent to punk music. And a generation of older writers whom I admired were based here—Norman Mailer, Don DeLillo, Truman Capote. New York had a literary center at that time, which I eventually discovered at George Plimpton’s house, on East Seventy-Second Street, the same apartment that housed The Paris Review. That’s where I met a lot of the writers I’d read in college. But I was also attracted to what was happening downtown, worlds away. I spent a lot of time exploring the nightclubs and music clubs, places that were not yet chronicled in any general-interest publication. It was a word-of-mouth, underground scene—drug fueled, pansexual, and spontaneous. When I arrived in the city, it was still possible to hear the Ramones play at CBGB and Iggy Pop at the Peppermint Lounge, and the Talking Heads were the reigning downtown savants. You could stay up all night at AM:PM and bump into John Belushi in the bathroom. The Mudd Club was this incredible scene. On any given night you’d see Jim Carroll and Lou Reed and Andy Warhol and Basquiat. I was just a fly on the wall, I could barely get into the cool places before Bright Lights, but I found it all very inspiring and I wanted to capture that energy and to create some kind of literary equivalent to the art and music scenes. It was a great time to be young and restless in New York. I wasn’t getting much writing done, but I like to think I witnessed a great moment and I internalized it.

INTERVIEWER

How did you pay the rent?

MCINERNEY

First I read slush at Random House. My best friend from Williams, Gary Fisketjon, was an editorial assistant there, working for Jason Epstein. I read unsolicited manuscripts all day. I also wrote freelance book reviews, mainly for the Village Voice. Then I did some research for Jane Kramer, The New Yorker’s European correspondent, and she eventually recommended me when a job opened up at the magazine. So I became a fact-checker at The New Yorker.

INTERVIEWER

Famously. What was that experience like?

MCINERNEY

I felt like I had really arrived because—well, it was The New Yorker. But it was the fact-checking department. I wanted to be in the fiction pages, but still. It actually paid pretty well, and I was seeing great writers like John McPhee and John Updike coming to visit William Shawn. J. D. Salinger was still calling on the phone. There was a terrific buzz about the place. But it was also a little depressing. There were all these unwritten rules. Like, for instance, if you were a fact-checker, you didn’t speak to an editor or writer in the hall—it just wasn’t done. Also, it turned out I wasn’t very good at it. And ten months after I got there, I was fired, and left ingloriously with my tail between my legs.