John Barth

“You decide to be a violinist, you decide to be a sculptor or a painter, but you find yourself being a novelist.”

“You decide to be a violinist, you decide to be a sculptor or a painter, but you find yourself being a novelist.”

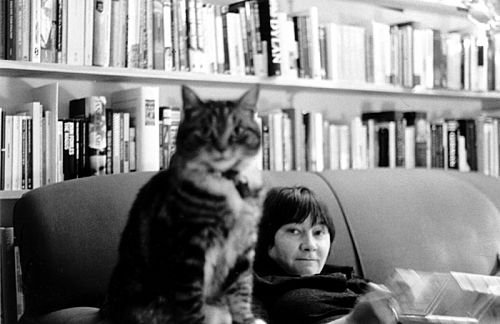

In his open, omnivorous writing on literature, visual art, and performance, Hilton Als has made critical analysis and introspection a conjoined practice. The essay, which he has called “a form without a form,” is his primary mode, and he invariably interweaves family and friendship, American fixations on and lived experiences of race and sexuality, metaphor and reality.

“My nights are a nightmare, quite often, but the nightmares are rich. I nourish myself by those nights.”

Independent, skeptical, laconic, and always lyrical, Rae Armantrout is a poet of wit and precision. Her poems are typically built of brief sections and short lines in which every word and syllable has been carefully weighed and placed. She also values alacrity and surprise. Arcs of argument can end midflight or spring abruptly in unforeseen directions. The tone shifts, and shifts again. The rewards of her quicksilver verse are many: she helps, as William Blake once put it, to cleanse the doors of perception. You look anew at everyday things and delight in language’s myriad marvels and traps. You also laugh out loud.

“There are all kinds of books I’d like to write that seem to be out of my grasp.”

“The really good ideas are generated in the process of writing, and only if you're working at white heat. You don't get those ideas if you're worrying about the commas.”

“Writing a story is like crossing a stream, now I’m on this rock, now I’m on this rock.”

“I don’t think one really gets permission to do things. You do them because you have to do them, and nothing else will do.”

“A book has got to smell. You have to hold it in your hand and pray to it.”

“The author is the successor of the saint, everyone respects the author.”

“There is no one truth, but there are an awful lot of objective facts. The more facts you get, the more facts you collect, the closer you come to whatever truth there is.”

“Like everyone, I know some big words, but I try my damndest not to use them.”

“In truth, I’m still slightly embarrassed to say, I am a poet. I’d rather say, I make poems.”

“Smart people say such dumb and disappointing things about translation.”

“I think pornography is a very rich medium, and I’ve studied it closely and learned quite a lot as a writer from it.”

“It knocked you off your horse, taking LSD. I remember going to work that Monday, after taking LSD on Saturday, and it just seemed like a cardboard reality.”

“I find what happens in reality very interesting and I don’t find a great need to make up things.”

“I was a kid who liked art and theater and dance and music, but if you lived in Harlem, high culture was somewhere else, and it wasn’t black.”

“The process of book writing for me is entirely one of trial and error.”

“I’m a person with virtually no feelings.”

On American Psycho’s Patrick Bateman: “The more he acquires, the emptier he feels. On a certain level, I was that man, too.”

"It’s because you’re always fighting sentiment. You’re fighting sentimentality all of the time because being a mother alerts you in such a primal way."

“Every novelist should possess a hermaphroditic imagination.”

“What I want to do is write something that seems like it means something and doesn’t. I want to write a novel that even I don’t understand.’

“What happened to poetry in the twentieth century was that it began to be written for the page.”

“Coming from New York, when I was a kid, anything west of the Hudson was out of this world.”

“As a girl—twelve, thirteen years old—I was absolutely certain that a good book had to have a man as its hero, and that depressed me.”

“When I was younger, the main struggle was to be a ‘good writer.’ Now I more or less take my writing abilities for granted, although this doesn’t mean I always write well.”

“I wanted to make room for antiheroes.”

“That’s the hardest thing to do—to stay with a sentence until it has said what it should say, and then to know when that has been accomplished.”

“I meant my first novel to be an epic which would contain, in an artistic narrative, ‘everything I knew.’”

“On January 10, 1974, Transports et Transit Maritimes Associés came to the rue de Tournon and took away three large metal trunks and I closed the Paris office of The Paris Review for good.”

“A strict form such as mine cannot be achieved through improvisation.”

It’s a little strange to encounter Michael Hofmann in Gainesville. He has taught creative writing for over twenty years at the University of Florida, whose sprawling campus is dominated on its northern edge by a football stadium, the Swamp, where orange-and-blue Gators chomp their unlucky opponents. A short drive from there, you can pick your way past dozens of real gators, dusky green and preternaturally still, in the Paynes Prairie Preserve, which is also home to herds of wild horses and bison. How the bison got to Florida, and why they stayed, must be an interesting story. In one of Hofmann’s few Gainesville poems, “Freebird,” written after his first visit in 1990, he quotes D. H. Lawrence: “One forms not the faintest inward attachment, especially here in America.”

“I was rather a goody-goody as a child… It was only later on I discovered that you could be naughty and get away with it.”

Born in London in 1945, Richard Holmes has written ten biographies and books of biographical essays. Even in his early works Shelley (1974) and Coleridge: Early Visions (1989), Holmes demonstrates a keen eye for place and a striking empathy for his subjects.

“I think that when one is dead one should be a little bit bolder, so that the rest of us may have some record of how things actually were.”

“It isn’t exactly true that I’m a provocateur. A real provocateur is someone who says things he doesn’t think, just to shock. I try to say what I think.”

“I often think of the space of a page as a stage, with words, letters, syllable characters moving across.”

“I know that black life, like all life, outstrips our perceptions, that so much of black life still remains—to invoke Ellison here—invisible, unseen.”

“Until I can read a story physically, with the eyes, it doesn’t seem to exist for me.”

“I tried to depict the human face of this history, I wanted to write a book that people would actually want to read.”

“What’s a revolution? It’s when a regime can no longer control the populace, when the regime is brought down to the ground.”

László Krasznahorkai was born in 1954 in Gyula, a provincial town in Hungary, in the Soviet era. He published his first novel, Satantango, in 1985, then The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), War and War (1999), and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming (2016).

“In some ways [the Internet]’s definitely an enemy.”

“If a word that was used by Flaubert or Césaire falls into desuetude, if it becomes passé, we still keep it in the dictionary because it was used by an important writer.”

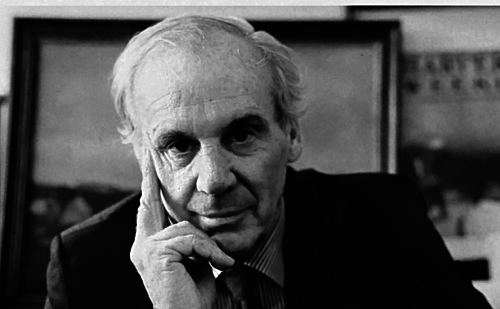

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

By the time I arrived in New York in the late seventies, Lapham was established in the city’s editorial elite, up there with William Shawn at The New Yorker and Barbara Epstein and Bob Silvers at The New York Review of Books. He was a glamorous fixture at literary parties and a regular at Elaine’s. In 1988, he raised plutocratic hackles by publishing Money and Class in America, a mordant indictment of our obsession with wealth. For a brief but glorious couple of years, he hosted a literary chat show on public TV called Bookmark, trading repartee with guests such as Joyce Carol Oates, Gore Vidal, Alison Lurie, and Edward Said. All the while, a new issue of Harper’s would hit the newsstands every month, with a lead essay by Lapham that couched his erudite observations on American society and politics in Augustan prose.

Today Lapham is the rare surviving eminence from that literary world. But he has managed to keep a handsome bit of it alive—so I observed when I went to interview him last summer in the offices of Lapham’s, a book-filled, crepuscular warren on a high floor of an old building just off Union Square. There he presides over a compact but bustling editorial operation, with an improbably youthful crew of subeditors. One LQ intern, who had also done stints at other magazines, told me that Lapham was singular among top editors for the personal attention he showed to each member of his staff.

Our conversation took place over several sessions, each around ninety minutes. Despite the heat, he was always impeccably attired: well-tailored blue blazer, silk tie, cuff links, and elegant loafers with no socks. He speaks in a relaxed baritone, punctuated by an occasional cough of almost orchestral resonance—a product, perhaps, of the Parliaments he is always dashing outside to smoke. The frequency with which he chuckles attests to a vision of life that is essentially comic, in which the most pervasive evils are folly and pretension.

I was familiar with such aspects of the Lapham persona. But what surprised me was his candid revelation of the struggle and self-doubt that lay behind what I had imagined to be his effortlessness. Those essays, so coolly modulated and intellectually assured, are the outcome of a creative process filled with arduous redrafting, rejiggering, revision, and last-minute amendment in the teeth of the printing press. And it is a creative process that always begins—as it did with his model, Montaigne—not with a dogmatic axiom to be unpacked but in a state of skeptical self-questioning: What do I really know? If there a unifying core to Lapham’s dual career as an editor and an essayist, that may be it.

—Jim Holt

INTERVIEWER

You started your career with the San Francisco Examiner.

LEWIS LAPHAM

My reasons for going into the newspaper business were twofold. One, to learn how to write. When you’re young you tend to use too many adverbs and adjectives, to think every word you come up with deserves to be engraved in marble. I hoped to cure myself of the habit acquired while writing papers at school and college.

The other reason was to get an education. Having grown up in Pacific Heights in San Francisco and then gone to prep school in Lakeville, Connecticut, and to Yale College, I knew I’d been living in a privileged, safe space and didn’t know much of anything about the rest of the country. Didn’t know how the politics worked, where the water came from, how the garbage was collected, who was living on the wrong side of the tracks. As a newspaper reporter, I expected to learn who were my fellow citizens, where and what was the American democracy.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s back up. Your grandfather was the mayor of San Francisco when you were a boy.

LAPHAM

Also a shipowner, the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company. Intercoastal trade. The ship would start with dry cargo in Seattle, go down the West Coast, through the Canal, around the Gulf, up the East Coast to Portland, Maine, and then back on reversed compass bearings. A very profitable business before the interstate highway system. On December 7, 1941, we owned a substantial fleet of ships. In early 1942, the United States government commandeered all of them for the North Atlantic convoys. Most of them were sunk by German U-boats. If I remember the story correctly, we were never reimbursed for the loss.

INTERVIEWER

As a boy, what were your passions? You must have read widely.

LAPHAM

Books were my boyhood. I can remember my mother reading Moby-Dick to me when I was six years old. Each evening I had to know exactly where the story had left off the night before or she wouldn’t read the next page. So I learned to stay with it. My father had a large library, he was himself a constant reader.

INTERVIEWER

And a writer, too. He was a columnist for the paper, right?

LAPHAM

Had been, yes. My father came back to San Francisco after graduating from Yale in 1931 to work for the Examiner, on occasion speaking directly to William Randolph Hearst, then enthroned at San Simeon. Under pressure from my grandfather, my father gave up journalism to become president of the family company.

And then my grandfather was elected mayor in 1942. He sometimes would go out to meet the aircraft carriers coming in from the war in the Pacific, take me with him in the launch, bring me up to the bridge to meet an admiral. When I was ten years old I wanted to become a navy carrier pilot. At Yale I didn’t qualify for the naval reserves because I was color blind.

INTERVIEWER

So what did you do?

LAPHAM

I was also in love with words. I tried my hand at poetry at Yale, and later at Cambridge in England, attempted to write in imitation of Yeats, Auden, Donne, Shakespeare, and A. E. Housman.

INTERVIEWER

The poetry you wrote back then, it scanned?

LAPHAM

It did. At Yale I discovered classical music and that also was an influence.

INTERVIEWER

You were already trained as a pianist?

LAPHAM

No. The house in San Francisco offered a fine view of the bay, but it wasn’t furnished with a piano. My parents listened on the Victrola to Cole Porter, Fred Astaire, and the Great American Songbook. At Yale I met Beethoven, Bach, Handel, and Mozart.

INTERVIEWER

Who was the first composer that moved you?

LAPHAM

My first lessons were on the harpsichord because I wanted to play Bach.

INTERVIEWER

So when you went on to Cambridge, you had an amateur interest in music and keyboard. You were there to study history.

LAPHAM

Medieval English history. At Magdalene College, I met C. S. Lewis, who had just come over from Oxford. I met Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Admired the poetry of Robert Graves, wrote him letters in Majorca. He didn’t write back.

At Cambridge, I was never in any kind of inner circle. I wandered around, audited lectures, wrote poetry, acted in plays. It was a lovely year, but I understood at the end of it I was not a scholar. I didn’t have the patience for footnotes. My parents were unwilling to fund my further education unless I was going to make an academic career.

“The good effect of translating is this cross-pollination of languages.”

“One of the things [fiction] does is lead you to recognize what you did not know before.”

“Some cynical biographer said to me, Make sure it’s a good death. Make sure you’re not picking someone who just declined.”

“The book attained a mind of its own, a subjectivity or an autocatalytic machinelike quality.”

“I want to create absurd and hilarious, but also dark and revealing, edifices of language.”

“I’ve got the fucking gift for it. Instinct, call it.”

“A novel should reflect its society and its circumstances.”

“The 'I' character in journalism is almost pure invention.”

“I only became a novelist because I thought I had missed my chance to become a historian.”

Before I met Alice McDermott, I’d heard a story: when her students became distracted with excitement after she won the National Book Award for Charming Billy (1998), she settled the class down by offering a hundred dollars to anyone who remembered the last winner. As the rumor went, she kept her money. Not one M.F.A. student of fiction could recall the winner or the book (Charles Frazier, for Cold Mountain).

This is a revealing wager from a writer as recognized by awards committees as McDermott; her novel That Night (1987) was a finalist for the National Book Award, the PEN/Faulkner Award, and the Pulitzer Prize; At Weddings and Wakes (1992) was also a finalist for the Pulitzer. Charming Billy won an American Book Award as well as the National Book Award. Child of My Heart (2002) was nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. After This (2006) was yet another finalist for the Pulitzer. Someone (2013) was long-listed for the National Book Award and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. The French translation of her most recent novel, The Ninth Hour (2017), received the Prix Femina étranger.

“It was a great time to be young and restless in New York. I wasn’t getting much writing done, but I like to think I witnessed a great moment and I internalized it.”

“With nonfiction, you’ve got your material, and what you’re trying to do is tell it as a story in a way that doesn’t violate fact, but at the same time is structured and presented in a way that makes it interesting to read.”

“Is there such a thing as overreading? Just because it wasn’t part of my grand design doesn’t mean it isn’t there. Things do happen in books that the writer is too submersed in bringing the narrative to life to notice.”

“All my editors have been white.”

“Language is so different from life. How am I supposed to fit the one into the other? How can I bring them together?”

“People loved to talk about how Frank O’Hara didn’t really care about getting published. That doesn’t jibe with my experience.”

“I just want to see whether it’s possible to entertain Freud’s fantasy of a realistic biography. It may not be a possible thing to do.”

“I feel as if I start in a kind of wilderness, and I’m sort of making a way, a crossable path through it. Eventually I can realize where a poem came from—but that’s rarely what the poem is about.”

“There is an immense abyss between the very few who have money and the vast number who are poor.”

“Writers had better not be too cocksure that they’ve got inspiration on their side.”

“I think of America as my audience, and inside that space are white people as well as people of color.”

“I worked at a library and that’s where I first read James Baldwin. I think it was Notes of a Native Son. It stopped me cold.”

“I must love big novels, because that’s what I’ve written. It takes a while before you begin to breathe the air the characters breathe.”

“Those who have earned respect should be given respect, regardless of their human faults.”

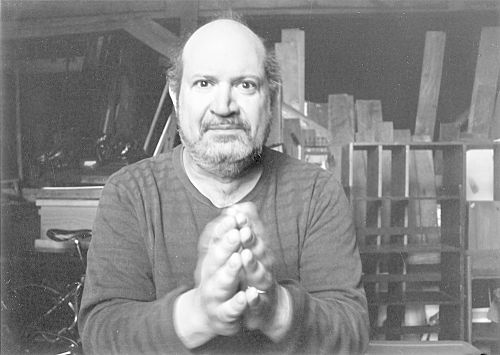

My first meeting with George Saunders took place in his home of ten years, a ranch house in the Catskills. The house stood on fifteen acres of hilly woods, crisscrossed by narrow paths that he and his wife, the novelist Paula Saunders, had cleared over many afternoons, following mornings spent writing.

The Saunderses had lived in upstate New York for three decades; they raised their two daughters in Rochester and Syracuse, two of the region’s Rust Belt cities, and Saunders’s first three story collections, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996), Pastoralia (2000), and In Persuasion Nation (2006), are marked by the experience of bringing up children and holding down jobs in a postindustrial economy. But the stories aren’t constrained by the conventions of gritty realism. There are ghosts, zombies, prosthetic foreheads, and memories uploaded onto computers straight from human brains. Many of the stories are extremely funny, many have endings of great emotional power, and most are written in a style that’s spare, vernacular, and very catchy. Appearing in The New Yorker since 1992, they won Saunders a MacArthur Fellowship in 2006 and have exerted an enormous influence on contemporary American fiction. The many writers who love Saunders often complain that it takes great effort not to imitate him.

In recent years, Saunders, too, has worked to write less like Saunders. Tenth of December (2013), shortlisted for a National Book Award, found him experimenting with new voices; in one story, “Escape from Spiderhead,” the narrator imbibes a drug that causes him to compose sentences in the style of Henry James. Saunders followed that book with his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo (2017), set in nineteenth-century Washington, far from the futuristic office parks and theme parks of his early work. It debuted at the top of the New York Times best-seller list and won that year’s Man Booker Prize.

Saunders and I spoke in his kitchen over mugs of strong coffee. Furniture was sparse, because he and Paula were moving. They’d decided to sell the place and live full-time in their house outside Santa Cruz, California. But the shed where he wrote Tenth of December and Lincoln was still as it had been when he was working on those books. His desk, flanked by bookshelves, faced a table displaying perhaps ten framed photos of Buddhist teachers in robes.

Anyone else might have easily written off a life of Véra Nabokov as impossible. In the two major biographies of her husband—both written during her lifetime, when she controlled access to his papers—she is a cipher.

“I love going to plays. There’s a subconscious side to it, obviously–some people like to be spanked for XYZ psychological reasons, and I like to go to plays, and I can’t entirely explain why.”

“There weren’t too many books by women that were taught in school, so I read those on my own, and the books I read were as accessible as the ones we were reading in school.”

“Fiction tells you, by the making up of truth, what really is true. That’s all fiction writers can do.”

“Before you have the assumptions implicit in the first sentence, anything could happen. But once you have that sentence, you’ve narrowed your options down to a point where there really isn’t that much left to write.”

“I don’t know why, but I always feel a kind of necessity to write things that are beyond acceptance, that are too offensive or something. For people to read them and say, Ha-ha-ha, very funny. No, we can’t print that.”

“In general, the food world … it’s just so against our nature.”

“I think cartooning gets at, and re-creates on the page, some sixth sense ... in a way no other medium can.”

“TV writing is for people who hate being alone more than they hate writing.”

“I think the writer has to be responsible to signs and dreams. If you don’t do anything with it, you lose it.”

“Before the film is finished, I have to be able to put into words why I have selected each shot and the meaning I attach to the order of the sequences.”