This fall, we’re recapping the Inferno. Read along!

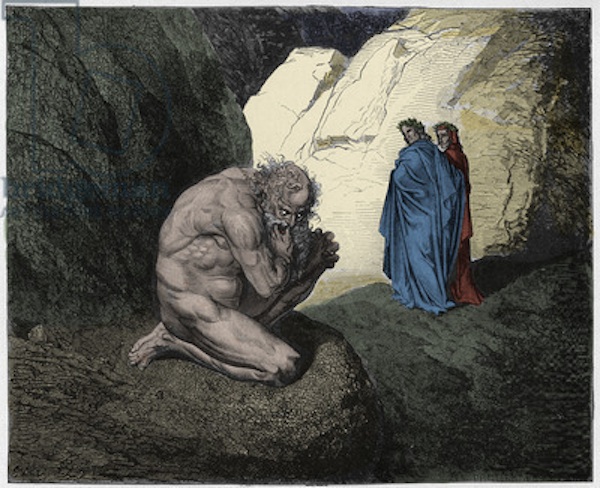

Illustration credit Gustave Doré.

“Something is gnawing at the nape of your skull: on the one hand, your favorite fall shows are coming back. But you just read an article about synaptic pruning, the process by which your brain eliminates neurons that don’t get any exercise. And whether or not there’s any truth to this neurological use-it-or-lose-it theory, you’ve nonetheless come to the conclusion that your brain is on the brink of self-destruction. Which is to say: it will get rid of every neuron that hasn’t got anything to do with watching Netflix, looking at Buzzfeed, or eating food that’s terrible for you past 3 A.M.”

Recapping Dante: Pilot Episode, or Canto 1

“Really, this is how you want to begin? With a trope? And do you really think that we’ll let you get away with it because you decided to double down, fold it over on itself, and begin not only in medias res but in the middle of your life, too? We see what you’ve done there. Very fancy; but couldn’t you have at least started at the end, like Sunset Boulevard?”

“It’s called a remix. That’s how this segment begins. It’s a living pastiche, a breathing exercise in allusion and homage. Every scholar seems to agree that the opening lines of this canto are Virgilian, but none know exactly which passage Dante is imitating. And that’s probably because Dante isn’t imitating a particular passage, but is simply borrowing his style; it’s Virgil re-invented—Virgil’s flow, but freestyle and on the fly, and in a completely different language. The simple fact that Dante can invoke Virgil so effortlessly not only points to a certain aptitude for getting into Virgil’s bones, but even suggests that Dante knows Virgil’s poetry better than Virgil probably knew it himself.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 3, or Abandon Hope

“I am writing this from the lobby of the Ace Hotel in New York; as I ascend from the basement with Dante under my arm, I see the following text printed on the stairs: EVERYTHING IS GOING TO BE ALRIGHT. This inscription offers an appropriate contrast to the opening of the third canto, which gives us the famous line written above the gates of hell, a line so famous that many know it well without knowing exactly who wrote it: ABANDON ALL HOPE, YOU WHO ENTER HERE. And just like the inscription in hell, these words too are written in the hotel’s neo-Victorian “dark hue.” But whether or not Dante knows it, he and I are essentially reading the same sentence—as chilling as the inscription is, the words in canto 3 ultimately do not apply to the man who travels beside Virgil.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 4, or the Halloween Special

“Full disclosure: canto 4, despite the ominous nature of canto 3’s ending and the fact that 4 is meant to open in hell, is not that scary. There is a distinct shortage of zombie/ghost-chase/door-gag montage scenes in this segment, and almost no haunted houses. So, we are probably meant to assume that Dante decided to take this holiday episode in a slightly more cerebral direction—he’s skipped right over the cheap scares, and has decided to hit us with a sort of theological horror show. Indeed, as Dante awakens from his spell, and walks beside Virgil, he notices that his guide’s face is stricken with a fearful pallor. When Dante inquires, Virgil informs him that it is not fear, but pity, that has altered his expression; the pair are entering limbo, where those who might have been able to enter paradise, had they lived in the time of Christ, are instead forever confined. Which is to say, no matter how saintly you are, if you had the misfortune of being born during one of the richest cultural eras in human history (like Virgil himself), you’re still out of luck, if not in hell proper.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 5, or A Note on the Translation

“With multiple translations come disagreements—different scholarly notes, interpretations, and even titles. But often what allows a translation itself to become a great work of literature can be determined by something as subtle as the phrasing of a single idea.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 6, or Crowdsourcing

“As we find ourselves in the midst of Nielsen sweeps month, it seems a good time to consider the facto that can ensure the longevity of certain shows. Yes, critical acclaim is great, but in the end, critics are only a small fraction of a high seven or even eight-figure audience turnout, and critics certainly don’t get a show a spot after the Super Bowl. For this, we rely on the viewers, and this week, it’s their turn to speak.”

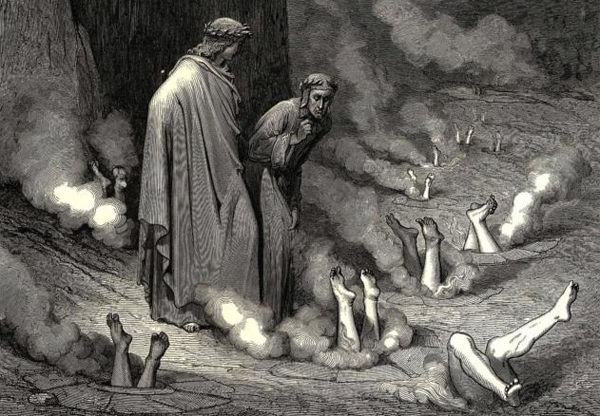

Illustration credit Gustave Doré.

Recapping Dante: Canto 7, or Hell by the Numbers

“Canto 7 opens with Plutus, the god of wealth, babbling unintelligibly at Dante and Virgil. Pape Satàn, pape Satàn, aleppe!, he shouts, a phrase that has left readers and scholars baffled ever since it was written. Many offer their own interpretations, but there is never enough evidence for any critic to settle definitively on a single meaning. Virgil, however, responds to Plutus as though the cry is somehow intelligible to him; Plutus doesn’t want to let the pair pass because he has been tasked with keeping the living out. Again, Virgil works some Roman magic and is able to pass by.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 8, or High Drama

“Canto 8 is perhaps the most exciting we have encountered so far. The story alone is a harrowing prelude to a great adventure: it’s like the first few minutes of a Bond movie, right before the theme song and titles start rolling. Canto 8 ends just as Dante and Virgil arrive at the edge of the Styx, where the wrathful are punished. Dante spots two towers (not to be confused with those from Lord of the Rings). These towers appear to be communicating with one another—as one launches a flame into the air, the other responds. A curious Dante asks Virgil what this signifies, and Virgil doesn’t really address his question. By now Dante has learned not to press such an issue, and knows that if he allows himself to get derailed by a mystery like two flaming towers, he’ll never get anywhere.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 9, or Dial V for Virgil

“A coarse, heavy rain pattered against the side of my cap, echoing like the sound of a rhythmic hailstorm pelting the skulls of sinners. The fumes from a black bog forming around the storm drain, not too subtle and very close behind us, obscured everything. I must have had a bewildered sort of look on my face, which my partner—standing just a few feet in front of me—mistook for fear. An instant later he was on his way over, cigarette floating right above his lip like a perfumed bird working the counter at Macy’s, elbows propped up against the etched glass surface.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 10, or Why We Are Doing This

“There is a circle in hell reserved for the people who stop reading Dante and never make it to canto 10. If there’s ever been any question as to whether the Inferno is really a great work of art, the answer lies in canto 10. If there is ever any doubt that Dante is worth rereading always—perhaps every year, like the Torah—canto 10 will remind us. If somehow we forget what sorrow, or remorse, or horror, or despair looks like—if we forget that sometimes human beings are at once so callous, and strangely tender, there again is canto 10.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 11, or Foul Smells and Boring Theological Discussions Ahead

“As Dante and Virgil make their way through the City of Dis (and see the tomb of yet anotherpope), Dante has a moment very much like the one where you open the bathroom door at work and are assaulted by the fumes of a previous occupant’s abomination. Of course, in this case, it’s the smell of lower hell. Virgil gives Dante a few minutes to compose himself and assures him that he’ll find a way to make the time pass while Virgil describes the rest of hell. In many ways, canto 11 is a lot like canto 2—it’s a way of briefly making everything clear to both Dante and to the reader. It’s Virgil’s way of saying, I know what you’re thinking; did we go through six circles of hell, or only five? Well, to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I kind of lost track myself. Let’s briefly recap!”

Recapping Dante: Canto 12, or A Concerned Parent Contacts the FCC

“For the last several months my child has been watching the program The Inferno. I’ve had concerns about the moral integrity of this show since the beginning, but a recent episode, ‘Canto 12: Dante with a Vengeance’ is perhaps the worst of it. The episode, which I heard about from my son and then felt concerned enough to watch myself, begins as the two main characters meet a Minotaur. I’m not trying to have my son indoctrinated with pagan dogma. I mean, what is this? I’ll let my son watch a show about talking vegetables so long as they’re telling the stories of Christ, but there’s something so frighteningly glib about the mythological image of a Minotaur being placed in front of children. Is no one worried about the future of American youth? And while we’re on it, let’s talk about these Virgil and Dante fellows. There’s something going on there, and I can tell you exactly what: sin.”

Illustration credit Gustave Doré.

Recapping Dante: Canto 13, or Please Refrain from Touching the Shrubbery

“Once again we find ourselves lost in a dark wood. Dante notes that in this forest there is no actual greenery. (This is hell, after all. Where does he think he is, the New York Botanical Garden?)”

Recapping Dante: Canto 14, or a Finger-Wagging Editorial Letter

“I’ve received your manuscript for Canto 14 of the Inferno, and I have quite a few notes. The language and poetry of this passage is absolutely magical; a few passages in particular caught my attention, such as ‘The gloomy forest rings it like a garland,’ (line ten), which is such a beautiful way of phrasing it. And the expression ‘scorn for fire,’ on line forty-six, sounds like the title of a Philip Roth novel. You have a good ear for lyricism and your poem is a unique, fascinating glimpse into theology, history, literature, even love. You’re really carving out a niche for yourself in the Italian canon—kudos!”

Recapping Dante: Canto 15, or How to Talk to Your Teacher When You Chance Upon Him in Hell

“As Dante continues to descend through hell, guided by Virgil, I too read with a guide of my own—Robert Hollander, whose annotated edition of the Inferno I’ve been using to write about Dante every week. I’ve read the Hollanders’ notes on Canto 15 many times over, but I still find myself getting lost in it—Dante’s encounter here is unlike any other.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 16, or the Pilgrim’s Progress

“At this point in The Inferno, as Dante continues to test, stretch, and deplete Virgil’s patience, let us imagine for a moment what Virgil might say given the opportunity to write a performance review for the pilgrim.”

Recapping Dante: Your Midterm Exam

1. Dante is

(a) The poet’s first name

(b) The poet’s last name

(c) The poet’s performance alias, à la Madonna or Ginuwine

(d) The owner of the peak in the 1997 Pierce Brosnan vehicle, Dante’s Peak

Recapping Dante: Canto 17, or Dante Goes to Los Angeles

Executive Producer: Did everyone get the canto 17 draft Dante sent around?

Writer One: Oh, where do I even start? It’s pretentious, it’s dry, it’s incomprehensible. When it opens, we’re in the third ring of the seventh circle. There’s a serpentine monster the guys meet, but instead of checking it out or slaying it or whatever, Dante forges ahead and talks to some usurer guy who’s wearing a giant bag under his chin. He’s not too chatty, so then the focus turnsback to the monster—

Recapping Dante: Canto 18, or Beware the Bolognese

“Canto 18 is perhaps the unsung workhorse of the Inferno—at only 136 lines, it is filled to the brim with political commentary, mythology, personal attacks, and feces. There’s a distinct energy in the way this canto is written; even the obligatory geographical descriptions feel alive, and Dante, when he sets the scene, uses the word new: new suffering, ‘new torments,’ ‘new scourgers.’ In short, this is a sort of broad-spectrum dis track that deals with two different kinds of sinners: the panderers/seducers and the flatterers.”

Illustration credit Gustave Doré.

Recapping Dante: Canto 19, or Popes Under Fire

“By now, you have seen excerpts from last night’s episode of Mr. Alighieri’s The Inferno, Canto 19, in which Dante visits the ditch that punishes simony. We have filed a defamation suit and sent a cease and desist to Dante’s attorney, but there will undoubtedly be a public reaction. Rest assured: our lawyers are going to crucify this guy.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 20, or True Dantective

“Dante: I’ve never seen anything like it. The moment we entered the domain of the diviners, I knew right away something was very wrong. Some sick bastard went to town on them. Their bodies were contorted, their heads were twisted back 180 degrees so their tears fell down their asses. It’s the sort of thing nobody should see once. You spend the rest of your career trying to avoid anything like it again. I was almost ruined after that. But Virgil, he was fascinated.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 21, or a Middle-Schooler’s Essay

“As Dante enters the next ditch, he addresses his reader, saying he and Virgil have encountered things about which his “Comedy does not care to sing.” One has to wonder what Dante is seeing that makes him so overwhelmed. Upon reading the notes in the back of the book, a reader can discover that this area of hell is reserved for those who committed barratry, which, according to the American Heritage Dictionary, is “sale or purchase of positions in the state.” Because this sin is so similar to simony, which was punished in a recent canto, we can understand that Dante means for the reader to undergo a sequential experience—as our thoughts move from simony to barratry—and that the theme of this canto is motion. Following this theme, we can also see Dante go from a state of confusion and horror as the canto begins, and then to a state of fear as he encounters demons, and finally to a feeling of faith as he learns to trust the demons.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 22, or Don’t Play Too Close to the Tar Pits

“The opening lines of canto 22 have a two-sided brilliance to them. First, there’s the way Dante—who is, along with Virgil, now in the company of demons—breathlessly describes the movements of a cavalry unit, the way soldiers will tousle hand-to-hand on the battlefield with war horns sounding through the air. It’s a nice lyrical passage that sounds like a nineteenth-century Romantic poet trying to modernize Homer’s battlefield passages. But then, absurdly, Dante juxtaposes those battle scenes with this ‘savage’ band of demons.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 23, or Hypocrites Get Heavy

“Canto 23 opens like the thematic climax of a slasher flick. Virgil and Dante—picture a cinematic hero and his love interest—have taken the opportunity to escape the methodical watch of the serial killer. Or killers, in this case: our travelers have fled from a pair of the murderous Malebranche, whose naturally violent tempers have been exacerbated by the loss of their human plaything and two of their fellow demons.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 24, or Serpent, Ashes, Rinse, Repeat

“Let’s begin by addressing the fact that these similes are getting out of hand. In the early parts of his poem, Dante’s similes were often only three lines long. Now—just as he did in the beginning of canto 22, when he describes battlefield scenes while traveling with the demons—he presents us with a long, roving simile about a peasant who sees the snow melt and knows it is time to herd his sheep again.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 25, or a Trip to the Reptile House

“Canto 25 is known for having the least dialogue of any canto in the Inferno. It seems like a minor feat, but when you remember how many questions Dante likes to ask, and how long Virgil will typically spend explaining things, and how sinners really like to chat it up with the living, canto 25 begins to seem remarkable. In fact, Virgil hardly has the chance to explain anything at all here.”

Alessandro Allori, Odysseus Questions the Seer Tiresias, 1580.

Recapping Dante: Canto 26, or You Can’t Go Home Again

“Wrapped in a shroud of fire, sputtering words from the tip of the flickering flame—this is how Ulysses appears to us in canto 26. As Dante approaches the eighth pouch of the eighth circle of hell, he sees sinners in flames; he knows he’ll find Ulysses among these ‘fireflies that glimmer in the valley.’ The man is tied up in a flame with Diomed, both of them being punished for their ruse at Troy. Dante begs Virgil to let Ulysses speak.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 27, or Let’s Make a Deal with the Pope

“If we consider that for a general, the nature of commanding an army in battle is outsmarting or overpowering the enemy—what Aristotle calls necessary and probable behavior for men of their nature in their situation—the manner in which they accomplish their victories seems insignificant. We may begin to suspect that Ulysses and Guido gave fraudulent advice not in their military and political stratagems, but in their advice to themselves.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 28, or Unseamly Punishments

“Canto 28 opens with a very self-conscious address by Dante. He tells the reader that even if his writing weren’t constrained by the dictates of meter and form, he still would’ve had trouble describing the following scene. But he had no idea what he was talking about: canto 28 is marvelous and harrowing. Canto 28 is perfect.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 29, or Don’t Trust the Midas Touch

“Having read the incandescent poetry of cantos 26-28, it’s difficult not to feel as though Dante really phoned it in with canto 29. In fact, canto 28 is so hard to shake that Dante dwells on it for the first thirty or so lines of canto 29, weeping at the thought of the mangled sinners he’d met. Virgil rebukes him for his compassion, as always, and emphasizes the importance of moving on: he tells Dante they’re running out of time to complete their quest, which must have been Dante’s way of upping the stakes. Will our heroes beat the clock?”

Recapping Dante: Canto 30, or Triple X

“Dante has shown that almost every canto in the Inferno obeys a certain logic. First, Dante and Virgil enter a new circle or ditch; Dante notices a small cluster of sinners being subjected to a gruesome, albeit clever punishment (shit-eating for the flatterers, amputation and disembowelment for the schism-makers); then Virgil will encourage him to approach a sinner, who inevitably ends up being an Italian eager to tell the story of his life in a way that downplays the gravity of his sin.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 31, or Dante the Television Writer

“By now it is clear that this season’s sleeper star is the breakout show-runner, Dante Alighieri. His show The Inferno, an unlikely gem of narratological genius, has consistently stood out from the televisual pack, relying for the most part on the rarefied taste of its audience and the poignant, lyrical style of the head writer. This most recent episode, canto 31, is no exception.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 32, or Area Man Discovers Hell Has Literally Frozen Over

“After traveling nonstop for many hours through an array of chthonic geological obstacles, local political activist Dante Alighieri has found that the apocalyptic landscape has actually frozen over.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 33, or History’s Vaguest Cannibal

“Here we meet the last great sinner of the Inferno: Count Ugolino. Like the others, he’s a historical figure remembered today chiefly for his appearance in Dante’s poem; and in spite of everything he confesses in these few verses, we inevitably pity him.”

Recapping Dante: Canto 34, or “It Is Time For Us to Leave”

“My relationship with Dante can be traced back to a Saturday morning in 1994. My dad and I were standing in the rain on Sixty-Sixth and Broadway, and I suspected he was taking me to Lincoln Center for a concert. Instead, we stopped at a small park where a large, bronze statue was shrouded by nearby trees, hidden away from the city. That, he told me, is Dante.”

A colorized version of Gustave Doré’s illustration for Canto XXXIV.