Donald Evans started collecting stamps when he was about six years old. When he was ten, he became preoccupied with building miniature communities. He grew up on a take in New Jersey, and spent much of his summer days down on the beach, where he made his sand towns and houses and highway systems and cathedrals. They only lasted a few days, but each time they were destroyed, he built better ones. Indoors, he made little villages on top of the family ping-pong table with Dinky Toys and plastic houses and tiny cardboard boxes that he painted lo look like buildings. He built mansions on his bedroom floor. He shared this activity with a best friend whose family was well-travelled and had a fascinating house full of collections of old objects and encyclopedias; his mother played piano and sang in Italian while the youngsters built their mansions upstairs. “My visions about my towns, most of them based on fantasies of Europe and royalty, came from playing around that house and listening to her sing.”

He and his friend competed in the sand building their towns—both working fanatically in miniature—even making dictionaries, Bibles and thumb-indexed encyclopedias for their rival characters (Evans’ was The Queen, his friend’s Untie Rich Harvest). These two also competed to out build each other and control more area and make more lavish and inventive palaces for themselves.

Quite soon it occured to Evans that he could make his villages more real by making stamps for them. “It was vicarious travelling for me to a made-up world that I liked better than the one I was in. I’m doing that now too. No catastrophes occur. There are no generals or battles or warplanes on my stamps. The countries are innocent, peaceful, composed. Sometimes I get so concentrated in these worlds 1 get confused . . . it’s hard to get out.”

By the time he was fifteen he had made about 1,000 stamps—modeled on the stamps in his collection — from about forty different countries which he kept in a three-volume set of composition books entitled “The World-Wide Stamp Album.” But then he gave it up. He was in high school then and from being an introverted kid he began getting involved and interested in people. “I began going steady with a cheerleader and going to football games instead of sitting home and making stamps. I got very hung up on being accepted and being like everybody else.” He didn’t know what he wanted to do, but his vague idea was to become an artist. “I thought you had to be like Dc Kooning and paint giant abstract expressionist canvasses. That was what people were painting then in the late 50 s. So I painted big abstract paintings. I would tell my parents I was going out to paint and I’d go down to the shore of the lake where I had made my sand cities and down there I’d smoke and make drawings and then go back and work on my huge paintings. A large oil named ‘Moonrise’ won first prize in a local competition and people said I had a lot of talent. The World-Wide Stamp Album lay in the bottom of a dresser drawer.”

Evans graduated from high school in 1963 and went to Cornell; he decided to be an architect. After graduation in 1969. he came to New York and worked for Richard Meier. He realizes now that he thought he could go on building his towns in a professional way. But architecture discouraged him—his most obvious reaction is that he has almost never drawn buildings on his stamps. Still, he credits the architectural influence in the involvement he has with solidity and balance—and also how the stamps are arranged on a page, whether in rows or triangles or diamonds or columns. “Architecture is very rich in its disciplines. Those years of drawing tiny little bathroom details on architect’s plans maintained a level of visual discipline that I’d always had from making those stamps and the villages and bookcases and the tiny little books.”

All this time Evans had saved his childhood stamps. He showed them only to intimate friends because he thought they were too “weird” and that no one would have use for them. One day a friend of his, the graphic designer, Barry Zaid, who worked at the Push-Pin Studios showed them to Milton Glaser, who wanted to publish them in Audience magazine, which unfortunately folded before che portfoiio could appear.

When he finally quit his job at Richard Meier in 1972, Evans took the stamps with him to Holland—along with a stock of carefully perforated typewriter paper to use as his canvasses: he knew he was going to paint mote stamps.

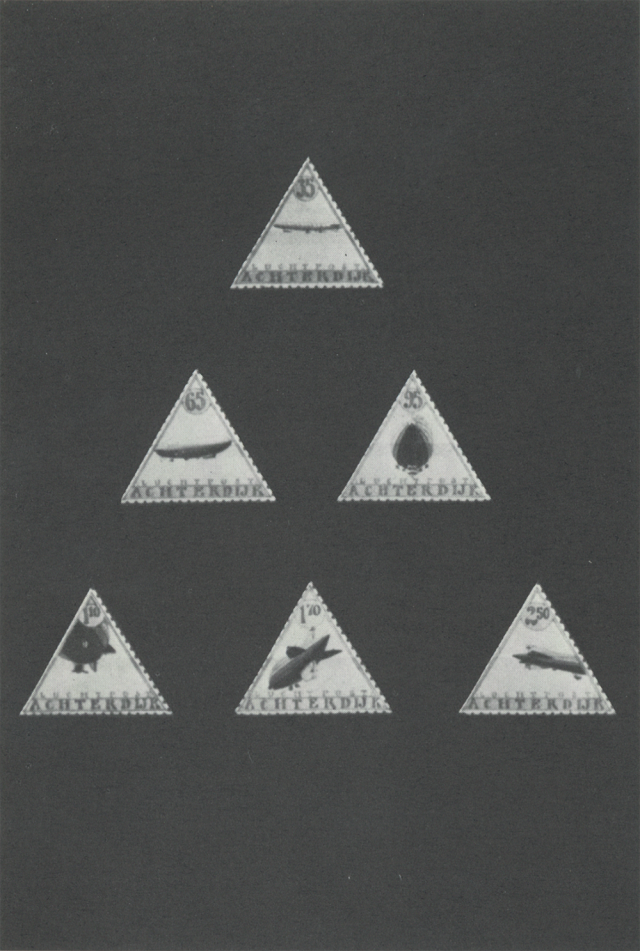

He was living in the village of Sthalkwijke on a little road called Achterdijk which in Dutch means “behind [he dike.” He began painting at a table by the window in the house along the railway. “It was a terrific release after working in New York. My first stamps were designed for a number of different imaginary countries named after Dutch friends, and also after Achterdijk. A dealer in Amsterdam offered to sell them for me—which encouraged me to make more. I began to get involved, and more sophisticated technically.”

Since then he has made almost 2500 stamps from about twenty-five countries named for and describing friends and interests all meticulously kept track of in a 250 page volume entitled Catalogue of The World, “which is now in its eighth edition. Some of the countries have as many as 200 stamps—certain places are so compelling and with so many possibilities that I just keep going until I get bored."

Evans is necessarily vague about where these places are. “I don’t like to make references to real plates on my stamps though I use existing languages. The stamps are more a kind of diary or journal. I hesitate to write down my made-up histories because I like to keep them open . . . and that is so 1 can continue to make more stamps ... ”

Evans uses a number two Grumbacher brush for his delicate work. He has used the same brush for the last three years, plucking out the hairs until now he feels that to work with a new brush would be like painting with a “Hershey Bar.” Often he paints from photographs. “I can’t shut my eyes and see, say, a camel, and draw it; I don’t have chat gift. But the images don’t necessarily come out looking like the photos. I have a visual image of the stamp right away, but I have a hard time deciding colors.”

All his stamps have an issue date, “My issue date corresponds to the design and coloration of the stamp and establishes them in a point of time. I tend to make old-fashioned looking monothromatic stamps. They were my favorite ones when I was a stamp collector, especially British and French colonial stamps which were so romantic and informative—little palm trees holding up strolls, things like that. But I avoid using real stamps as models or soliciting them because I don’t want to be influenced.”

Evans uses postmarks both to make the stamps look more real and to obliterate certain mistakes. “I’ll cancel over the stamp to deliberately obscure things or just to be perverse, to establish a certain layer of distance from the work.”

Friends often ask him, “Would you do stamps for real countries?” “It’s tempting.” Evans replies, “but 1 don’t feel like sitting down with all those graphic designers or chose government committees around a conference cable CO change things around until by the time you’re done you’ve got a second rate conceptual image.

-- M. M.

“To my knowledge there are no artists who make scamps in the way I do. But there very well may be. It’s like the question of whether we are the only planet in the universe with people on it. I just don’t think we arc. I’m curious, but I also dread finding there’s someone in ...Paraguay or Switzerland or somewhere who is doing exactly what I do, and doing better. Throughout my life I’ve tended co withdraw if there was someone else doing better what I wanted to do. So chat sore of competition would kilt my interest in making stamps. It really would. I’d have to give up my world of stam“When I moved from New York to Holland in 1972, it was to the countryside—Achccrdijk 27. Schalkwijk (Utrecht), and it was there that I began again co make scamps. So Achterdijk was one of the first Dutch words CO be learned: Achrer-dijk (behind-che-dike) struck me as perfectly Dutch—a surrogate for Nederland: Neder-land (Nether-land). These airpost stamps were to record the approach and passage of a mail-carrying dirigible, painted in the dull colors I like to use to help suggest stamps of the period ... ”